The written record of gay history is, by and large, a charge sheet. A list of crimes. When same-sex desire became formulated and medicalised into ‘homosexuality’ in the late nineteenth century, we began to see the start of a corpus of homosexual literature, but one that, inevitably, was the preserve of a class who could afford to protect itself from the implications of self-expression. Gay literature is a light canon. But a gay culture? Oh boy, was there a gay culture. It just wasn’t written, but instead passed, if you will pardon the expression, from tongue to tongue, an oral culture of languages and legends, protocols and habits. Bourgeois society can both record and develop its culture in the written word, but marginalised societies can face repression, imprisonment, or even death if they write down their desires, if they write about who they are. A love letter in an evidence bag.

Queer culture instead found an ephemeral form. Drag, cabaret and other performance, of course: stuff that could find a way out at night, in the dark, under cover of alcohol. But other forms of oral tradition, less performative ones, made up gay and queer culture too. Ways of describing gender not recognised within the wards, ways of describing power relationships not found on the psychiatrist’s couch. Languages to describe opportunities and dangers. Undrawn maps of where to get a decent blowjob in this town. And more; amongst gay men, of filmstars and singers who meant something to them, not just as individuals, but as a culture. Amongst trans people, a registry of support or of less-dangerous medical care. There are more examples, many more, that intersect and overlap between identities which themselves intersect and overlap, because this is a culture, after all.

What’s unusual about those codes, knowledge and traditions is that they were, by necessity, not passed down within families, like a lot of cultures. Instead, when young queer people found their way to bars, cafes and social spaces frequented by other queers, they could be slowly inducted into a society that reached far beyond just sex. As such, queer culture became intergenerational, passing down and evolving over decades, with continuities and fractures. All these forms of oral culture made up a way of reproducing, in a non-biological way, a gay life. Some of those are evident in a series of documentaries made in the first years of the 1980s by London Weekend Television which profiled gay male life in the UK capital at the time, and in the past, through interviews and archive footage. The show, in fact, was called Gay Life, and a few episodes are available to watch for free on the BFI player.

In Being Gay in the Thirties, an episode of Gay Life from 1981, two old friends meet in the top room of the same gay pub they visited 50 years earlier, as young men. They sit in JB’s, the upstairs lounge of The Old King’s Head, a now-closed gay bar on Bear St, just off Leicester Square. “The men who drank in the upstairs bar at JB’s called themselves sisters”, the narrator explains. The two men, the fabulously named Gifford Skinner and his friend, casually reminisce on their social lives at time, referring to themselves and their friends using female pronouns, with traditionally women’s nicknames, like “Rosie Both-Ways” who, Gifford remembers, was also known as “Russian Rosie”. His friend interjects — “Do you remember Lady Lavender, with the two white borzois?”

Later the men visit “The Lily Pond”, a ‘camp’ name for the upstairs tearooms at the Lyon’s Corner House, where sympathetic ‘nippys’ (waitresses) would seat them together. The Lily Pond was a famous, or infamous, gay hangout for almost four decades, and its reputation lead to men who thought they might be what Gifford called ‘musical’ or ‘so’ visiting the tearoom and being inducted into the cult. Much is made in the documentary of the use of feminine pronouns and camp names being indicative that homosexuals at the time regarded themselves as a “third sex”, as indicated by the fact they’d then go to cruising grounds and pay “real men” [read: ‘heterosexual’ and/or working class men] to fuck them. But that neglects to account for another reason why gay men developed such a culture: it drew them together, bonded them over their differences from mainstream, heterosexual culture.

The Lily Pond is a recurring venue in Matt Houlbrook’s seminal history of the city at the time, Queer London. He describes gay men’s use of commercial venues like bars and tearooms as being analogous to the way mainstream urban culture conducted itself, but if “men’s use of commercial venues was culturally familiar, they simultaneously transformed London’s pubs and restaurants into the site of a visibly different world”. Using commercial venues enabled a world of relative safety and socialisation that necessitated and facilitated the development of a gay culture, such as the use of camp names, fashions and tastes. Obviously these differences intersect with other, equally complicated factors, not least regarding class and gender presentation. ‘Queans’, men who adopted the most flamboyant manifestations and affections of gay culture, even had their own cant language, Polari. Formed from a combination of different influences, and shared in part with other groups such as seamen, showmen and sex workers, Polari was a way to both avoid detection when among non-queers, and to stand out to each other. Houlbrook describes how Polari, “in mapping the cultural organization of queer urban life — “the things most usually discussed” — this “vocabulary” allowed queans to talk about a world that was “their own”. What clearer example can there be of the oral nature of a developing gay culture than a language that spanned centuries?

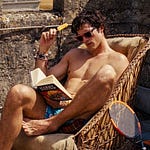

The importance of collective culture to a gay sociality is still pre-eminent in two other episodes of Gay Life, also filmed in 1980, titled ‘Heaven’ and ‘Male Sexuality’. In ‘Heaven’ the film tracks across a number of gay venues, including the Royal Vauxhall Tavern, and the different cultures they engendered. Drag queens at the RVT discuss their memories of Polari, at this stage a language on the point of extinction: “it’s a way of talking with each other without the ordinary people knowing what you’re on about”. ‘Male Sexuality’ is also focused on Heaven, where men at the bar discuss their attitudes towards sex and relationships, and the networks of emotion, desire and conflict that mark them out. But the film ends on a touching note, given added pathos today by our knowledge of the cataclysm that would tear this scene apart over the following decade, as all the men agree that, over and above sex, it’s friends that matter to gay culture. “Gay friends are very important to other gays. You can’t survive without them,” a cute northern twink says. Another guy who features in both documentaries says “Rather than get emotionally tied up with a partner, we tend to make good, strong friends…. Friendships last a hell of a long time on the gay scene”. The last man states it most clearly. “They’re the things that make your daily life bearable. They give you support... Certainly I think friends are more important than sex.”

This collective culture that is created and shared between queer people by word of mouth, and by friendship, the thing that makes certain cultural things “gay” and others not, constitutes something else: an audience. For the performer is only one half of the show; for the culture to make sense, it needs to be interpreted, read, and understood. A gay culture apart from a straight mainstream has, by necessity, a different read on the world, and a different history of influences, a different sensibility produced by the fact that we lead different lives, experience things in a different mode. I’m sure some will feel rejected by this claim, others will feel it is too broad-brushed a caricature, and will shout that I can’t speak for them, as tedious gays always do when you make a claim for the collective. But I do not care because I have been in that gay audience and have felt the touch of that sensibility upon my very core and nothing, nothing has ever effected me so profoundly. That audience is what produces culture, one that rolls between camp and fury, that understands the importance of being having been taken aside by an older gay and told you have to see this performance or that, because this is part of who we are.

“An audience is more than a group of passive consumers,” wrote the critic Herbert Muschamp, discussing the importance of a gay audience to New York in the 20th century. “It can be a productive unit as well. An audience produces demand, a stage, giggles, an erotic charge (limbic resonance), a texture of thought or climate of opinion that ripples outwards into a the larger social milieu. It produces a baseline of expectations, the pressure to maintain or raise it, and the memory to recognize when and how far it has slipped.” Working hard to improve the quality of enjoyment — what a collective task to undertake! The principles are laid down in that early theorisation of faggotry, Susan Sontag’s Notes on Camp, where she proposes that “Camp taste is, above all, a mode of enjoyment, of appreciation - not judgment. Camp is generous. It wants to enjoy...Camp taste is a kind of love, love for human nature. It relishes, rather than judges, the little triumphs and awkward intensities of "character." . . . Camp taste identifies with what it is enjoying. People who share this sensibility are not laughing at the thing they label as "a camp," they're enjoying it. Camp is a tender feeling.”

Muschamp’s thinking is as useful to me as Sontag’s: queer culture reproduces a model of life that has saved literally millions from despair and isolation, and it does so by passing itself around, person to person, through collective memory, enjoyment, appreciation, spurring itself on to improve enjoyment. So what happens when there is a sudden rupture in the ability of an oral culture to reproduce itself?

It is appalling that we do not have to wonder. We can instead look to our urban queer centres and how the devastating losses during the early stages of the ongoing AIDS crisis have transformed them. In her astonishing book The Gentrification of the Mind Sarah Schulman accounts in detail the social change that occurred following the deaths of large populations of gay men from AIDS in New York in the 1980s and early 90s. “It was normal to hear that someone we knew had died and that their belongings were thrown out on the street. I remember once seeing the cartons of a lifetime collection of playbills in a dumpster in front of a tenement and I knew that it meant that another gay man had died of AIDS, his belongings dumped in the gutter.”

I recoiled the first time I read that. Despite being raised during a time when AIDS and homosexuality were synonymous threats, and despite coming out after HAART treatments became available to some HIV positive patients, it wasn’t until I reached Schulman’s account of a dumpster full of playbills that I got, in the stomach, what a toll it must have taken. The mortality rates are terrible numbers, but the image of a lifetime of care and enjoyment and love passing with nobody to remember it hit hardest. This is the damage that Muschamp recalls in his own essay on a gay audience:

The seasoned gay audience… The audience with memory; the crowds of people who can recall the echoes of ovations, hoots, and silences, reverberating down over the years, season after season, decade after decade; the audience that can remember a time before innocent perversity calcified into postmodern irony: this audience has fallen prematurely silent. A quarter century has passed since the first cases of AIDS were reported in the United States. The duration of the epidemic now spans more than a generation. Officially, it has claimed the lives of almost 140,000 New Yorkers. That represents more memory than even the greatest city can afford to lose.

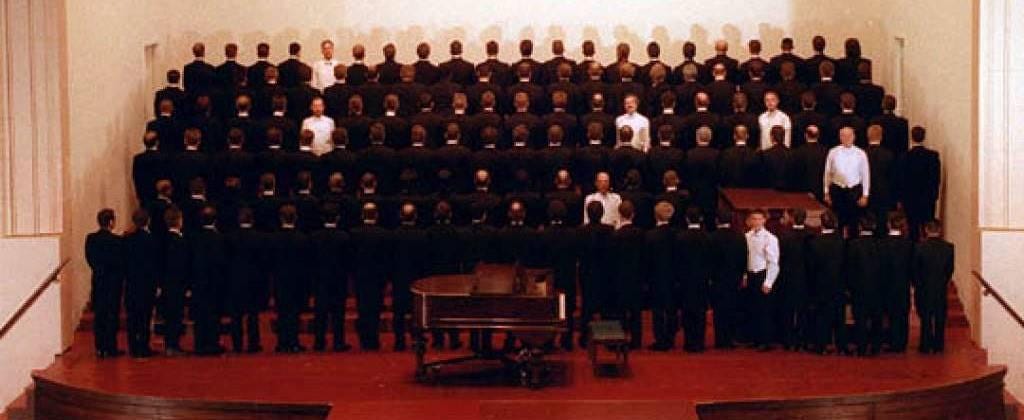

There is another striking and simple demonstration of this sense of cultural loss. In 1993 San Francisco Chronicle photographer Eric Luse took a photo of the Gay Men’s Chorus, with a few men dressed in white, and the rest, with their backs to the camera, in black. The caption read “The men in white are the surviving members of the original San Francisco Gay Men’s choir. The others represent those lost to AIDS.” What went with them? A cultural memory of what it meant to be gay and proud in San Francisco in its most wild and exciting days. Stories of what it meant to endure. Only three years later, Luse wrote that, were he to take the photo again, there would be no white suits. “The obituary list is now 47 names longer than the chorus roster. For each man singing these days, more than one chorus member has died of AIDS." In the years that followed, before the curtain rose, members of the chorus would say together “I sing for two”.

The losses of the AIDS crisis, the collective and individual trauma that many survivors felt and still process, and the ensuing gentrification of both cities and cultures that Schulman documents, resulting in a collapse of queer social spaces and bars, has created a lacuna, a missing gap, in the oral culture of queer lives. There are few bars left for young and old queers to mix, however fractiously, and for people to learn in person, face to face, what being gay might mean. Where the bars do exist, there are too few older voices to fill them, and a dying culture of sharing between generations. Despite, or perhaps because of, this lacuna in our collective memory, there is an increasing awareness of what are termed “queer elders”. But too often there’s a gulf of understanding between older and younger queer generations.

That gap was illustrated in the latest series of Tales of the City, a long running set of miniseries released over the past 30 years based upon the novels of Armistead Maupin. The novels, originally serialised in the San Francisco Chronicle, revolved around intergenerational queer narratives, centred upon an elderly trans woman, Anna Madrigal, whose little block of apartments becomes a refuge for outcasts and drifters, often queer. Anna’s worldly and non-judgmental wisdom, acquired over a lifetime of hardship, was the beating heart of the books, but in the recent Netflix revival of the show there’s a new tension between queer generations. The latest is the only adaptation set after the catastrophic years of the AIDS crisis in San Francisco, and the original gay character, Michael, now in his late 50s, introduces his young twenty-something boyfriend Ben to a dinner party of his old gay friends.

As they recount their shared anecdotes of the good old days, Ben politely objects to the use of racist and transphobic slurs, and the dinner grinds to a halt as one of the old queens responds:

I really don’t appreciate that we have to be policed [at a gay dinner party]... A bunch of fags bullshitting around the table… Why is your generation obsessed with labels? You look at me and you see what? A rich white man? Is that my privilege?... Let me tell you something about visibility and dignity. Any so-called privilege we happen to enjoy at this moment was won. OK? And by that I mean clawed tooth and nail from a society that didn’t give two shits if we lived or died and indeed who did not care when our friends started to die. When I was 28 I wasn’t going to fucking dinner parties. I was going to funerals. Three or four a week. All of us were.

Ben: I understand that, I do

Oh you do? Really? Because you saw Angels in America? Fuck that. FUCK THAT. You have no idea. This world that you get to live in. With your safe spaces and your intersectionalities… this entitlement you now have to dignity and visibility as a gay person. Do you know where that came from? Do you know who built that world? Do you know the cost of that progress? No, of course not. Because it would be more than your generation could ever bear to comprehend… I will not be told off by someone who wasn’t fucking there.

It’s a remarkable and uncomfortable scene, one of the only times I’ve seen the intergenerational tension of our moment represented without the caricaturing of at least one of the two positions. That’s not to say the show doesn’t take a line; it quite clearly, and rightly, tackles the assumptions and privileges that do still exist even amongst people who have faced such devastating trauma. After Ben leaves the party he points out how wildly presumptuous and inaccurate it is to claim that a young black man living in America doesn’t know what it’s like to live in a society that doesn’t care if you live or die, and the show clearly makes a strong case for the importance of a politics that does challenge the assumptions of, in particular, white, middle class, and cisgendered gay men. Furthermore, their defence of casual transphobia and racism thrown about as “jokes”, justified on the fact that they survived the crisis, erases the fact that the crisis was not, as is often depicted in cultural representations, a gay white male disease. People of colour, trans men and women, and cis women, were all affected, and were often key actors in all manner of political and social responses to the crisis. But the scene also demonstrates the truly felt position of some older gays that the younger generation doesn’t understand the nature of the trauma they faced, and this two-way gap in understanding, left unaddressed, is causing a poisoning resentment and political conflict.

To an extent, the line about Angels in America hit home particularly strongly with me; faced with the loss of so many voices, and the difficulty in generations to talk in person with each other about how and why they feel the way they do, a mediated form of cultural dialogue has taken its place. Queer people born after the 80s do, on some level, understand that the political struggles of that era are part of our culture as queer people. Films, television programmes and, to a lesser extent, books, have become the portal by which most younger LGBTQ people learn about a period that is easily within living memory of their elders. An uncomfortable aestheticisation of the period of particularly US-based AIDS activism is underway, one built from an intention to honour and mirror the struggle of queer elders, but which can miss the mark by mistaking representation then for action now. The aesthetics of organisations like ACT UP came from the material circumstances in which the struggle took place. Those circumstances have shifted, yet in a troubling way the signs and symbols have begun to attract a kind of retro fashionable cache without necessarily leading to a similar political critique of current conditions.

The cant language, the slang, of young, white cis gay men in the UK, for example, is much more likely to be derived from the largely black and latinx queer ball culture of the US, and largely that scene in the 1980s, than from any culture passed down to them from British queers. TV is your mother now, daahhhling! It’s through the film Paris is Burning, and in a further mediated version of that scene in RuPaul’s Drag Race and on the internet, that the specific language of US ball culture has become ubiquitous in Europe. And that’s not inherently either new, or a problem; European queer culture has always been influenced by the cultural megalith of the US, and London has had friends of Dorothy as long as Hollywood. But its consumption detaches it from those who invented it, gobbles it up, and removes the relationship of the culture, as Houlbrook said of Polari, to “the things most usually discussed”. Ball culture developed as a way for people “talk about a world that was “their own”” as well, yet today that language has been taken from those who developed it out of necessity, and sold as an affectation to a new audience. It should be clear from those mediated representations that ball culture was not intended simply as entertainment; it was a way for queer people of colour to survive and thrive in an extremely hostile, racist and transphobic world. Cultures aren’t, and shouldn’t be, preserved in formaldehyde, of course. The nature of culture is that it transforms, mutates, influences and synthesises. But that process of influence and synthesis is not neutral, and is rife with exploitation, with taking and merchandising people’s culture formed in the face of exploitation, without control, recompense or acknowledgment.

More than that, the nature of the culture industry is always to distance the political from the now, in terms of time and space. Manufactured, mediated queer culture is important, of course, but seems to take two forms now: the political past, as seen in films like 120 BPM, and series like Pose, or the personal present, with programmes like Queer Eye. Collective struggle against material problems are located safely in the past, while today’s problems are solved through personal growth, learning and loving yourself, making the most of your life, born this way, yasss queen. There is little to no space within mediated culture for collective struggles, and little to no way for an intergenerational connection from which to learn that the struggles of the past actually happened in a present.

A culture is not just what’s happening now. It’s a memory, a collective memory, of how we got to what’s happening now. It’s an audience to remember and understand a performer. It’s only through that collective memory that we can put today into context, see which raging novelties are mere misfires, and which are restructurings of who we are and how we think. The queer lacuna of both a health crisis and a collapse in queer social space has limited the ability of the queer audience to reproduce its own particular queer life, leaving both the young and the old vulnerable to loss. Recalling memories and sharing oral cultures seems imperative as we hope to exit our current crisis, and that relies upon rebuilding an intergenerational dialogue.

Thank you, as always to my subscribers. I hope you are all weathering this tough time as well as can be hoped.I was super stoked this week to learn I’ve been awarded a writer’s grant from substack. On top of the support I get from my subscribers, it felt great to be acknowledged for what I’ve tried to make this essay series over the past year, and couldn’t come at a better time, as writers everywhere are seeing work drying up. Check out the substack post for other grantees – there’s some great writing there. Other stuff:

Bad Gays! This week we profiled the flamboyant forger Elymr de Hory. Listen here.

Red Tory reviewed at the LA Review of Books. Listen to the audiobook for free here.

Hannah Williams in The Bookseller on the economics of writing today. Great stuff.

Still loving Mr Lucas, a Facebook page posting diary entries from a terrible old gay in London in the 1960s. Mainly about how boring the civil service is, and how rough the men he pays for sex are.

One of my favourite newsletter, Close, is posting essays by 15-19 year olds about how coronavirus is affecting their lives right now. Really good.

Please feel free to share and forward today’s newsletter with anyone who might be interested. For those just visiting, I send out a newsletter/podcast a week to paying subscribers — for less than $5 a month — and one a month for free subscribers. You can subscribe here, and, if you like it, please hit the like button. It helps other people find my newsletter.