I learned recently that tinyletter, the email newsletter subscription service, was soon to close, which is something of an end of an era. Services like tinyletter bridged the lacuna between the golden era of blogging and our current age of subscription newsletter, something a little more professional although a little less charming that has again changed the form and the economics of writing online. This very newsletter started its life on a tinyletter I ran, and which many of you subscribed to, back in the day. To mark its demise at the end of this month, I thought I’d post one of my favourite pieces from that tinyletter, a piece that addresses cities, homosexuality, and a critic who remains of great interest to me, the late Herbert Muschamp. Enjoy.

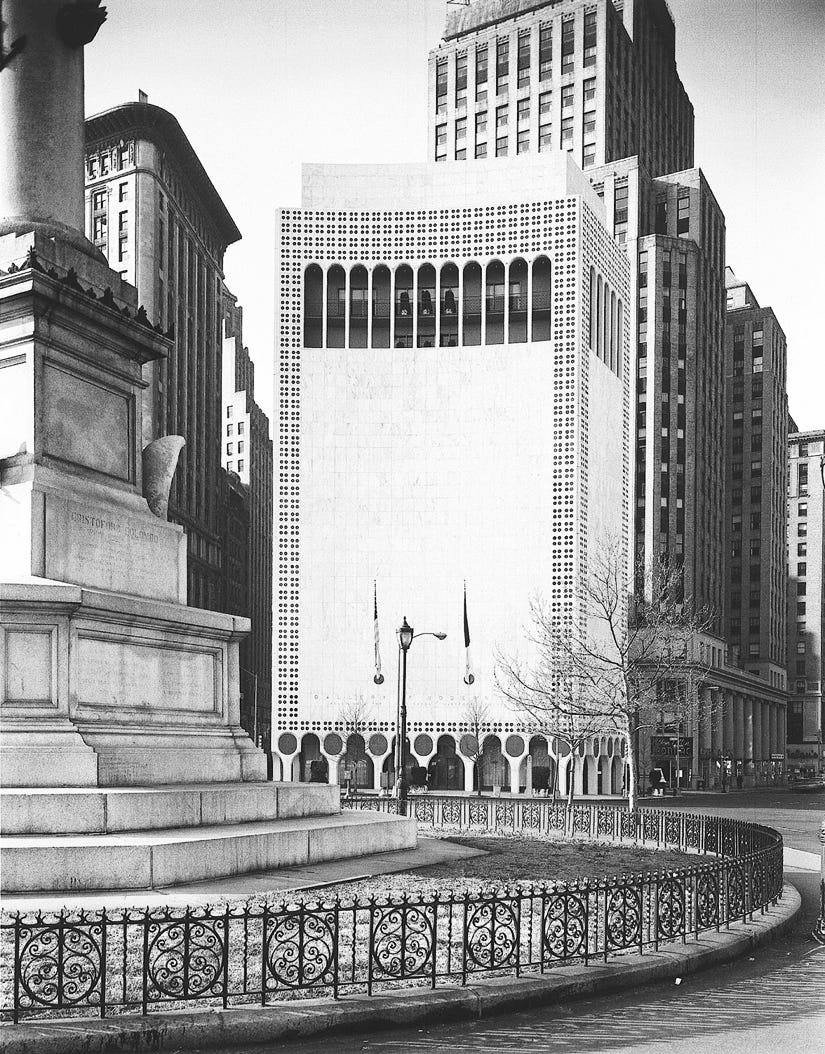

In his history of Edward Durrell Stone’s design for 2 Columbus Circle, New York City, built in 1964 to house the Gallery of Modern Art (GMA), the architecture critic Herbert Muschamp offers an critical examination of the role a “gay audience” played in establishing an alternative narrative to modernism in the city.

In fractious dialogue with the Museum of Modern Art, the collection housed at the GMA gave new significance and space to the Pre-Raphaelites and the Surrealists, disrupting the Greenbergian hegemony of the Abstract Expressionist movement in the city at the time. The All American Men of Abstract Expressionism produced an All-American Art: “the dominance of Abstract Expressionism over Surrealism looked a lot like the dynamic between high school jocks and the fairies they'd tortured”, he notes. The GMA, in contrast, provided a home for the fairies; a place where the overlooked aesthetic and political nuances of neglected and decorative movements could find their viewer.

2 Columbus Circle then :)

A gay audience, as in the architecture of 2 Columbus Circle as well as the gallery itself, produced not a reactionary yearning for the past, but a complication of the monolithic International Style that dominated New York architecture at the time, recognising that complexities, outliers and deviations tell us as much about our culture as the hegemonic aesthetic regime. Both building and collection, he wrote,

ran counter to the prevailing standards of High Modern taste with which the city asserted its postwar hegemony in the arts.

What these phenomena had in common was audience appeal - an appeal to the varieties of desire and conflict, to show biz, to memory, and above all to the open-ended heterogeneity of city life. You didn't see that in the perpetual reiteration of abstract paintings and glass towers.

These counter-positions to modernism's restrictive codes needed a stage, and a stage requires an audience attuned to the creative logic behind seemingly wanton events and who seizes the opportunity to help shape its own moment in time. That is where gay men came in.

To me, it’s a wonderful piece of criticism; it offers complications to the narrative of the culture of a city, and to New York’s planning specifically, whilst still offering a passionate, potent and witty defence of all that is great about urban life at a time when the trend was to encourage the shrinking of cities. “By the standards of Eisenhower's America,” Muschamp writes,

gay taste was perverse. In hindsight, it seems more like a corrective to the far greater perversity of postwar "progress." What kind of normality was it to imagine that abandoning American cities was a good thing to do? Goodbye, cities! Adiós, civilization! Good riddance to the repository of cultural memory, the incubator of ideas, the heartbeat of humankind.

Upon first reading it, thrilling to its tone, by turns learned and shady, I felt its focus on a gay audience and its relationship with a city’s cultural history illuminated an important division for me in my own writing. It felt natural, when I started writing about the subject of cities and homosexuality, to call it a “queer urbanism”, or “queer psychogeography”. The phrase felt more inclusive, and trendy, like I was taking into account the broad variety positions and subjects that we now know recognise. But perhaps a “gay urbanism” is more accurate, more honest.

Queer to me is not an identity, but an approach to identities. Queer is about undermining a fixed homosexual subject as the production of a heterosexual form of discipline; it is about positionality. Gay, on the other hand, is about the production of that identity within heterosexual discipline. “The elaborating of certain erotic preferences into a “character” – into a kind of erotically determined essence – can never be a disinterested scientific enterprise” wrote Leo Bersani (adopting a voice) in his introduction to Homos – “The attempted stabilizing of identity is inherently a disciplinary project.” But, like Bersani continues, there is nonetheless political and cultural value in that elaboration, and the “discrediting of a specific gay identity...has had the curious but predictable result of eliminating the indispensable grounds for resistance to, precisely, hegemonic regimes of the normal”.

An urban gayness is the product of a shared history and culture, diverse yet with a specific focus, passed down largely through the oral tradition and through a complex ecosystem of cultural production, through art and theatre, through camp and through political agitation. To me, the queer is a forward-looking and utopian political project aiming to undermine the secure subject position, to disrupt the regime of gender and sexuality categorization that is used to punish the deviant. I’m drawn to that political project, but I have always been someone who can only see the world I live in through the spectres of history. The gay, then – the specific and contingent, the flawed and corrupt, the lost and still living – holds me in its grip when it comes to my approach to the city. It illuminates the city and culture in the explication of its very prejudices.

2 Columbus Circle now :(

A gay urbanism understands the city through an approach that is askew to the mainstream, the heterosexual, the planned, but contingent upon it, existing as a lived experience only in relation to the attempts at control, order, and policing. I think that the historical imagination is ideally suited to the specifics of the gay city, rather than the political projections of the queer city. Please do not read this as a reactionary attitude towards the queer – or, at least, please accept my apologies as I search for the value in the specifics, and try to disrupt me if you will. Bersani continues:

We have erased ourselves in the process of denaturalizing the epistemic and political regimes that have constructed us. The power of those systems is only minimally contested by demonstrations of their “merely” historical character. They don’t need to be natural in order to rule; to demystify them doesn’t render them inoperative. If many gays now reject a homosexual identity as it has been elaborated for gays by others, the dominant heterosexual society doesn’t need our belief in its own naturalness in order to continue exercising and enjoying the privileges of dominance.

In historical specifics we can understand better a gay relation to the city as the city relates to gays. The city and homosexuality are almost coterminous in both history, homosexuality as a category emerging out of bourgeois moral panics of the new sexual conditions created by urbanisation, and physically, with urban centres providing the unique mix of darkness and light needed to generate a resistant sexual subculture. From those temporal and physical specificities emerge the stories necessary to create the contradictions and counter-narratives that offer alternatives, in the same way that the contesting cultures of cities provide counternarratives to the isolation of rural fags who find themselves drawn to urban spaces.

As Muschamp elaborates, those contingent new cultures of cities produce not just artists, or performers, but also new audiences. Audiences are themselves silos of memories and references, and are the catalyst that produces meaning and takes it out, from inside the galleries or clubs or theatres, into the world, in order to change perspectives, to change urban space. “In the 60's, the space of the audience expanded from the theater to the city at large. The energy that flowed into that setting was driven by adolescent hormones. We were eager to attach ourselves not only to one another but to the streets.”

Perhaps in further exploring our relationship with the city as a specifically gay experience, we can understand ourselves as an important receptive and productive audience. The AIDS crisis represented both a massive loss of, and a discontinuity in the oral culture that helped created, a gay audience. Muschamp laments this loss as being under-recognised in its significance:

Early on in the AIDS crisis, the city registered the cultural impact caused by the loss of gay artists. The effect produced by the loss of the gay audience is more insidious, however. An audience retains the memory of a performance. What happens to that memory when the audience is gone?

Those memories were never recounted to younger gays like myself; the skills never transferred, the slow realisation of the impact of urban histories on our senses of self having to be learnt from experience, rather than taught from experience. In picking up the pieces of our specific histories, we can produce challenges to a hegemonic regime which wishes to plaster our city in glass facades, much like they’ve done to 2 Columbus Circle, covering up the distasteful Venetian motifs, the Tiffany lamps, the dirty gay bars, the darkened nooks and crannies, the complex counter-histories to capitalism that don’t sell well but produce lives and loves and meanings and memories. Muschamp understands that “a vibrant city is perpetually recreated from the emotional depths, and from our socialized capacity to empathize with the memories of others”, and in remembering we can recreate our cities too.

‘Utopian Drivel’ is written by me, Huw Lemmey. If you’re a paid subscriber, thank you so much for your support. Please do forward this to anyone who might enjoy it.

If you aren’t a paid subscriber, please consider subscribing; paid subscribers also help support pieces for free subscribers! You also get access to the entire archive of 100+ essays, including posts such as this essay on the quality of phone screentime, this piece on Orton and Halliwell, this essay on depression through a mirror, darkly, and this report on watching the Queen’s funeral at a gay sauna. Free subscribers get occasional posts, like this guided walking tour around London’s world of queer espionage, or this double-header on the Gay History of Private Eye magazine.