Half Price Subscription Sale! It’s Christmas coming up, so I thought I’d give a special offer to new subscribers to Huw Lemmey’s Utopian Drivel. If you subscribe to my newsletter this month you’ll get a full 50% off an annual subscription. Treat yourself, or why not get a gift subscription for a friend who loves reading but already has too much clutter? To take advantage of this half price offer (and support independent writers), click the button below. Thanks, Huw

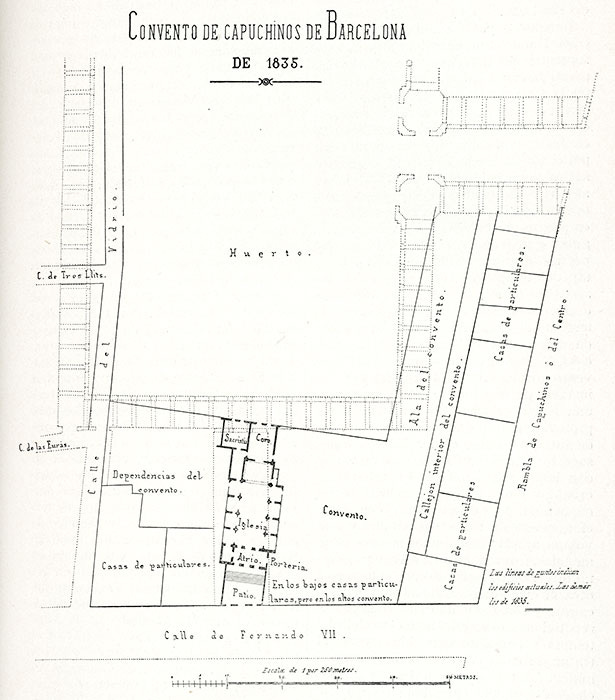

The Convent of Santa Madrona, which stood where Plaça Reial now sits

Some streets are good streets. Some streets are bad streets. I don’t why but I do know the difference. Some streets are cut-throughs. All streets are cut-throughs, really; even a cul-de-sac takes you somewhere. Their job is to link. But cut-throughs are even more linky than regular links, like the terrace back alley I used to walk down as a kid, taking me from my street down to the newsagents where once I bought sweets, and then Hooch Lemon. Those streets linked me to all kinds of fucked up. That’s where streets take you: to memories. It’s one of those Morrissey lyrics you’ll never be able to expunge, thank god, but I would rather not go back to the old house.

So this morning I was waiting at the haberdashery on Carrer de Francesc Pujol. In the square in front is an excavation of the tombs of Roman citizens buried along the road that left the city two thousand years ago. Romans always buried their dead on the roads outside the city walls, I believe. The haberdashers is a traditional shop, with racks of wooden drawers and shelves filled with reams of cloth samples and boxes of pins. Ahead of me each little old lady was ordering a few little things: a sample of offcuts used for quilting, a new set of needles for a sewing machine, and so on. Each one would order an item, and the shopkeeper would disappear into the back room and reappear, perhaps with a roll of cloth in hand, which he would lay on the long, dark wooden counter and unroll. With a pair of pinking shears and a wooden metre rule he’d cut the required length, then ask the old lady, in Catalan, “alguna cosa més?” - “anything else?” And there would be something else, and then something more. And with each lady the shopkeeper would exchange a few words, and then the lady would exchange a few words with another lady stood in the shop, and then would leave, and the second lady would walk to the counter and begin the whole process again. I stood leaning on a pillar, a bundle of bobbins and reels in my hand, feeling that strange sensation of frustration arising, a sort of pins and needles of the soul. But then I realised, and set myself straight. If, through the twists and turns of your fate, you’ve found yourself waiting in a haberdasher’s shop on a Monday morning, nothing in your life can be that urgent that you can’t wait your turn. So I wait.

Just off Carrer Ferran is a street that’s always been bad. That’s not something empirical, of course. Nor is it something negative; I like it, as a bad street, dark even though it’s well lit, too thin for anything much wider that a bicycle, quiet, and long, with no side exits. Its false prospect seems born from the fact that Plaça Reial was built much later than the surrounding neighbourhood, a 19th century bourgeois conceit fucked into the mediaeval city, to paraphrase Owen Hatherley on the Shard. Well, that’s how cities work; sometimes here the urban metaphors are a little too on the nose. The pretty neoclassical square replaced the Capuchin Convent of Santa Madrona (itself only early 18th century), the new order subsuming the old, just as Via Laietana, the broad avenue linking the homes of the new bourgeoisie in the extension district uptown with their warehouses at the ports, was smashed through the neighbourhood in which the mediaeval guilds had long resided. But this bad street has been here since the Romans, I reckon, with remnants of the city wall found at its edges, and since it’s held lionesses and women of the night, and all inbetween. It backs on to an old nightclub, one built as the dictatorship crumbled, and one that became a nail in it, a nail with all the threads of the counterculture snagging on to it. As I walked down it a few nights ago I walked down the bad street and saw a man stood, bent over against the wall by the nightclub fire escape. He leant his head against his arm, his leather sleeve a little cushion against the swaying stone. He rocked like he was on a ship. As we passed, we heard that unmistakable sound, when the stomach overrides the limits of the body and the throat opens to release a thick, heavy jet of vomit and bile. Flush, pause, flush, pause, flush. Across the feet, his shoes, and rising into the air, a miasma of acidic vodka painted the surfaces. He would still smell of it in the morning, but the street would be cleaned.

The plan of the convent overlayed over the street plan for the neoclassical plaça. Carrer Ferran was called Calle de Fernando VII

I arrived at my office on Plaça Reial a little after 11am, later than I had wanted. I sat at my desk and answered the emails that had accrued over the weekend. Pati, the little cat who lives in the office, was padding at my chest. The grim grey cloud that had loomed over the city when I left the house had dissipated and I looked out of the window of my office, which sits in a little attic on the top floor, onto the rhomboid of crisp blue sky that the neoclassical square frames. Around the top of the winter palms seagulls swooped and pigeons fluttered. As I looked back to my work, I got the sudden sense of commotion, perhaps in the corner of my eye. Like when there’s a fight on the very verge of kicking off on the street, sometimes you just sense in your shoulders that something is happening. I looked up and directly in front of my window, on the deep ledge overlooking the square, a seagull had a pigeon pinned to the stone. With an unexpected rigour he was pushing his beak deeper into the chest of the little bird, who, by the time I realised the gravity of the situation, was making his last moments on this earth, a few aggressive but stilted flaps of its wings, attempting to pound against the body of the gull. The enormous seagull had broken through the pigeon’s ribcage and had plucked its heart from its chest. Then it left back into the big blue square. I summoned the courage to assess the grizzly scene, but it was surprisingly bloodless, almost surgical: a small impact wound exactly in the middle of its broad, fluffy chest, and no heart, and its quiet, sad little face resting on the cold slab, eyes now closed to the winter, and that was all that. Another memory.

These linking streets in my mind are all dead ends recently. Old sadnesses bring old depressions. When I walk through the city I get a taste of what life had been for me. This restaurant here, the smile of a drunken friend in love, that corner there, a debt I had to pay. Up here an apartment where I had sex with a tourist, and there where I bought a bag of drugs, even though this morning everything is closed for Constitution Day. This is what makes streets, cities, the urb. It’s why I love some given neighbourhood, even though I remember my own vile sensation of vomit streaming through my own body, and why I can’t visit other ones, even though my mother held my hand there — or maybe not though, but because. Sometimes the streets don’t fit together in our minds; you take one thinking you know where it comes out, and you find yourself in a place you never wanted to be. So things close down. For others, it’s a public holiday, but for you, wanting to live, it’s just a row of shuttered stores.

If you aren’t a paid subscriber, please consider subscribing; paid subscribers also help support pieces for free subscribers! You also get access to the entire archive of 100+ essays, including posts such as this short story, “The Fantasist”, this essay on depression through a mirror, darkly, this one on “normalising everything”, this piece on Vox and homonationalism, and this essay on watching the Queen’s funeral at a gay sauna. Free subscribers get occasional posts, like this guided walking tour around London’s world of queer espionage, or this double-header on the Gay History of Private Eye magazine.