Normalyze This

do we need to normalise everything?

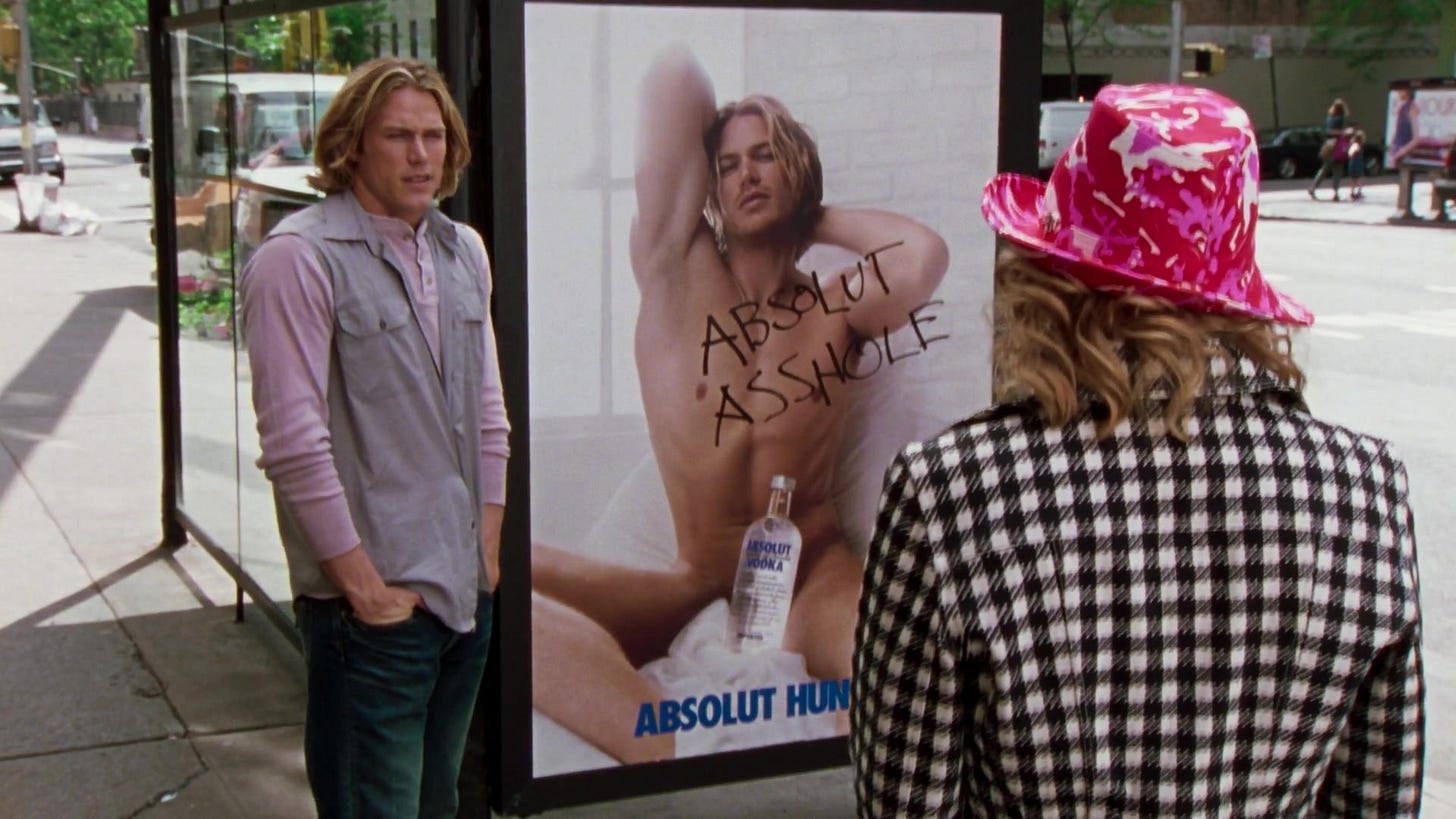

There’s an episode of Sex and the City in which Samantha Jones, the PR agent who is a stand-in for the viewers unrealised fantasies of true sexual freedom, is trying to explain how culture works today. Her client, a young, hunky model named Jerrod Smith, is the new face of Absolut, and his naked body, penis hidden by a strategically positioned litre bottle of vodka, is up on display on a billboard in Times Square. Despite being promised that the campaign would help the young actor break out of off-off-Broadway political theatre and into the mainstream, he feels like he’s becoming a figure of fun, a sell-out. Samantha is gently reassuring him that it will soon pay dividends, when a gay guy comes over and asks if he really is the “Absolut Hunk”. “I just wanted to say that my friends and I are huge, huge fans”. From over at the bar, a group of queens offer him a flirtatious salute.

“It’s working, what did I tell you!” Samantha beams, “First come the gays, then the girls… then the industry!” It was a different landscape back then, of course, but she was right. That episode, from Season 6, came out almost exactly twenty years ago, and for most advertisers, being associated with gay men was brand suicide. But we were at the start of the shift towards our current landscape, where gay men — or rather, a certain type of gay man — were becoming associated with something desirable: fun, style, and being ahead of the trend. Sex and the City was part of this shift in popular culture. It portrayed gay men much more sympathetically than a lot of TV at the time; while they were mainly bit characters, they lived rich, fulfilled lives, made money, spent money, and thrived as part of the social world in which the aspirational female characters lived. The fact the show was written and produced by gay men is probably the main reason for that; I’m a firm subscriber to the conspiracy theory that Sex and the City show was actually conceived as a show about four gay men, but knowing it would never be commissioned, the genders were merely swapped while leaving the plot intact.

Absolut was another player in this shift. The brand has been advertising itself explicitly to gay men since the very early ‘80s, in magazines like the Advocate, in gay venues, and in sponsorship of LGBTQ events. As such, it’s an interesting piece of product placement; I suspect few other alcohol brands would have allowed their products to be used, yet Absolut were actively courting gays in a storyline about how gays were trend leaders. Samantha, the SATC producers and Absolut all understood that gays were an emerging market, and that in normalising commercial relations with gays, they were normalising gays at the same time. The same logic emerged at the same time in the conservative case for gay marriage: normalise homosexual relationships, bring them into the same logic as heterosexual relationships, and you will capture the market for conservative values. This process was just as successful as Absolut’s. In making his case for gay marriage legislation in the United Kingdom, Conservative Prime Minister David Cameron would claim that “I don’t support gay marriage despite being a Conservative, I support gay marriage because I am a Conservative.” Admitting homosexuals into the institution was an attempt to revive marriage’s flagging brand.

Gayness had been normalised. But what does normalise mean? I think the implication is generally that it was society that had changed enough that gayness was now normal. But the object that the verb normalise is acting upon, the thing that is changing, is not society, but gayness. It is gayness has been transformed.

I suppose the threat was taken out. The mass social transformation that is coming out - the public acknowledgment of one's deviant desires in large enough numbers to undeviate them - has been quite astonishing as a political process, especially considering a massive epidemic and murderous moral panic hit barely a decade after it began in earnest. In his 1996 New York Times essay When Plagues End the conservative gay columnist Andrew Sullivan, a long-time advocate for gay marriage, suggested that although the AIDS crisis exposed the deep, inhumane homophobia of American society, it also turbo-charged the process of normalising gayness. For many, the choice of whether to come out or not was taken from them; dying of AIDS outed thousands of gay men across society who would otherwise never have made public their sexual orientation. Gays ceased to be a powerful hidden cabal and instead became an all-too-impotent generation of Middle America’s brothers and sons.

I’m far from a Sullivan fan but I think that’s a compelling argument. Yet Sullivan’s argument is not that it was AIDS that normalised gay men for America, but rather the political response to AIDS within the gay community. Pre-AIDS gay culture was dominated by the ideology of Gay Liberation, something, he argues, that was marked by a fundamental irresponsibility. Gay Liberation was a childlike state in which gays were second class citizens, denied rights in exchange for being denied responsibilities. It was, he wrote, “the Faustian bargain of the pre-AIDS closet: straights gave homosexuals a certain amount of freedom; in return, homosexuals gave away their self-respect.” Sullivan argued that AIDS forced responsibility — care — onto gay men and in the process turned them into political subjects with a stake in a liberal democratic order, wanting to marry and willing to fight in its wars. This echoed his article in the New Republic some seven years earlier, “Here Comes The Groom: A (conservative) case for gay marriage,” in which he argued that gay marriage would tame the irresponsible behaviours of gays with monogamy, showing a charming belief in the fidelity of both hetero and homosexual married couples.

I believe his argument, by accident or design, mischaracterises Gay Liberation as an idea. It seems to me that a gay liberation politics is not rooted in a desire to evade responsibility, but rather an abiding responsibility towards each other (and younger generations) in undoing the conservative social structures that clearly did so much harm to LGBTQ people. I think it also doesn’t give enough credit to the invaluable work gay liberation did in creating a homosexual identity and community that, when the AIDS crisis emerged, was cohesive enough to recognise and advocate for itself. When he acknowledges that “even the seemingly irresponsible outrages of Act-Up were the ultimate act of responsibility”, we can’t ignore that it has its roots in a pre-AIDS conception of a gay community. And I think for many participants, Gay Lib was entirely about conferring upon oneself a degree of self-respect: it was the respect of wider society that it gave away.

But whatever: I come not to bury Sullivan but to praise him, for I think there’s a strong argument to be made that both Sullivan’s logic and his politics have become the dominant ideology of gay life today. So successful, in fact, that it’s possible for many gays, Sullivan included, to gather comfortably amongst the pitchfork caucus during the latest, current iteration of a century-and-a-half-long moral panic about homosexuality and gender. Sullivan was right: normalising gays by bringing them into the fold has bolstered the sex-gender system that the Gay Liberationists were trying to unpick, and gays and lesbians are more than welcome alongside the pro-lifers and evangelicals as they portray variance from the sex and gender norms as a predatory conspiracy of powerful groomers, child-abusers and leftist anti-Americans.

What’s surprising is not that the archetypal white, wealthy American gay boogeyman has adopted a post-Sullivan politics. Whisper it, but class interests are still the organising logic of a class society. It’s that so many of the supposedly radical queers are post-Sullivan too, in their fundamental logic, if not their ideological positions. Normalise has become the imperative buzzword of a social phenomenon that followed this general normalisation. Normalise not having sex scenes in films. Normalise cutting out toxic friends and emotional vampires. Normalise getting your parents to pay for your therapy. You know the stuff. It is as if, in seeing the success of the normalisation of gays (rather than of male homosexuality, maybe), normalisation has become the marketplace, the territory, of successful political action. There seems to be only one feasible strategy: not to challenge the moral argument for “normalcy”, but to expand its capacity while keeping its limits the same.

A trivial case in point: I am old enough to remember when dating apps were far from the norm. People who met a lover or partner online constructed elaborate backstories as to how they “actually” met, at a museum or on the train, perhaps, to disguise the abjection and shame of online dating. When sites like Gaydar and GayRomeo, and then the app Grindr, were launched, there was a period of a few years where gays would discuss their hookups from the apps pretty openly among each other, but we would be much less likely to talk so openly about them with straight friends or workmates. There remained a stigma to getting laid using the internet, which stank of desperation, perversion, or even subterfuge, rather than the natural chemistry of the meet-cute. Gradually, that stigma seeped away as more and more straight people began using the apps, and this behaviour was “normalised”: that is, made legible to heterosexual culture. What had been other became us; what was once dehumanising became human.

I was thinking about this the other day when watching the gay BBC dating series I Kissed a Boy. In the episode a new delivery of gay men arrive in the villa, and one contestant, Ollie, a sweet lothario who oozes a sense of sexual libertinism, begins chatting up Dan, a newbie he fancies. He’s sure he recognises him and is trying to place the lad, who tells him “I probably sent you dick pics”. That wasn’t it, Ollie is sure, so he whispers under his breath “Do you go cruising?” Despite having just told him he had probably sent hm photos of his cock, Dan is shocked by the question, and its implication, replying “fucking hell! Fuck off!”. We cut to Dan sat on the couch, confiding in the camera: “that was a pretty interesting question to ask someone, right off the bat of meeting them!”

I thought it was fascinating how a once-abject act - digital cruising, planning to meet someone for sex online, or sexting, sending them hot photos - had been normalised by its proximity to heterosexuality, and the original sex culture - one that involves physically meeting someone, determining chemistry and attraction in-person first, something that to me seems eminently normal, something that indeed inspired cruising apps in the first place - had become more shameful in the process. I’m sure we could talk more here about the growing fear of the embodied, the increasing taxonomies of “types”, the fact we’re too anxious to answer our own phones anymore, but we won’t. It’s enough to merely use this as an example of how normalisation works: normality requires its inverse, abnormality, and abnormality must be further excluded if the normalised is to be included. Grindr has made IRL cruising weirder.

So calls to normalise things — and forms of queerness and sexual behaviours, specifically — are often reactionary forms dressed in radical words. As friend-of-the-stack Davey Davis wrote recently, “why is it that we must be fit, condensed, into their worlds in order to live? why is normalcy something that must be granted by straight people?” When people see behaviours, modes of existence, ways of being that are subject to repression or hatred, the imperative becomes to make them identities, and then demand that such behaviours are normalised. Perhaps we can do what Sullivanism did, and make them credible, legible to the norm, feasible, and therefore deserving of rights. It doesn’t work: white American male homosexuality has been swept up in the new moral panic along with all the other queers. Resisting normalisation isn’t an issue of posing as radical, of wanting to be edgy. It’s about acknowledging the fact that, as Davey says “normalcy does not exist without the abnormal.”

Perhaps we are not normal. Perhaps normal is no good. Perhaps normal is the thing that made us abnormal to begin with. I hope to become better at welcoming my abnormality, and in the process accepting and loving the abnormality of others. It’s no easy task: as I wrote last year, when I discussed disgust, in our society “...abjection - to be the object of revulsion - is to be unworthy of love. This is not just something preached from the homophobe’s pulpit, either, but is a belief that underpins a society constructed, at root, on the reproduced image, the once printed and now pixelated image. We live under the tyranny of the image. Disgust is to be erased, sanitised, purified, ejected. Only the immediately and crudely attractive, only the beautiful, is capable of being loved.” We don’t need to normalise anything: we need to reckon with our love of the norm.

I’m currently in Amsterdam for a resident at Woonhuis, attached to De Ateliers. On Tuesday 12th I’ll be giving a public lecture there. All welcome, you can find details on their Instagram.

‘Utopian Drivel’ is written by me, Huw Lemmey. If you’re a paid subscriber, thank you so much for your support. Please do forward this to anyone who might enjoy it.

If you aren’t a paid subscriber, please consider subscribing; paid subscribers also help support pieces for free subscribers! You also get access to the entire archive of 100+ essays, including posts such as this essay on Vox and homonationalism, this one on the Huw Edwards scandal, this piece on cultures of anxiety, and this essay on watching the Queen’s funeral at a gay sauna. Free subscribers get occasional posts, like this guided walking tour around London’s world of queer espionage, this double-header on the Gay History of Private Eye magazine, or this essay on the limits of gestures of allyship.