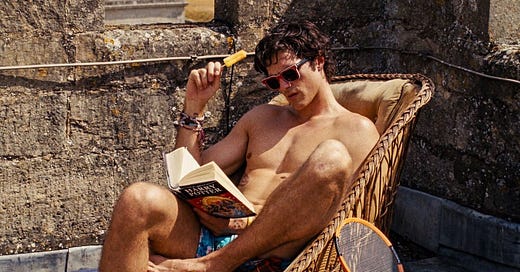

Jacob Elordi as Felix Catton in Saltburn

“Everybody hates a tourist,” whimpers Jarvis Cocker into his microphone, “especially one who thinks it’s all such a laugh.” He releases a tight, sardonic giggle. Yeah. Sure. And “the chip stains and grease will come out in the bath”. The camera pans across the crowd. 100,000 people standing in a field. As he returns to the song’s original tone — a deep, uncompromising sincerity that stares the listener straight in the eye and tells it like it is —the crowd pulsates. They don’t just know every word, they feel it. It’s 1995, at the Glastonbury Festival, and his headlining band, Pulp, are at their zenith. There have been 16 years of Conservative government in Britain, and their policies have further entrenched Britain’s class divisions and difference. Cocker’s song seems to press hard on the exposed nerve of huge numbers of young poor people excluded from the riches of Tory rule, just at the moment that working class culture is becoming cool. One really can’t over-emphasise how deep English people’s identification with this song, “Common People,” still runs. It says something important to us.

“Common People” tells the story of the frontman meeting a rich Greek student at the bar of Saint Martin’s, an art college in Soho, Central London, at the end of the ‘80s. Like most London art colleges were until relatively recently, the school was a strange menagerie of starkly different class and national backgrounds, where working- and middle-class oddballs trying to escape the provinces would mix with the feckless progeny of the global ultra-rich indulging in the most social and transferable of higher education pathways. This knowledge-devouring Greek goddess reads Cocker as a working class Northerner, is attracted to him for that reason, and tells him that she wants to live, and fuck, with common people like him. But what she will never understand is that everybody hates a tourist. The only problem is, I don’t think we do. In fact, I think the English love nothing more than a class tourist, especially one whose fare is paid through sex. If we didn’t, why is this fantasy of passing through someone else’s upstairs or downstairs world one we return to again and again, in music, film and fiction?

A decade on from the song’s release, at least in our own fiction time, and Lady Elspeth Catton, played by Rosamund Pike, is reclining in her rattan armchair outside Saltburn, her country home and husband’s ancestral seat. By the pond her children, Felix and Venetia, drape themselves across the ground in their swimwear. Oliver Quick, Felix’s working class university pal, hugs his knees. Babybird’s 1996 hit single “You’re Gorgeous” plays quietly on the radio, causing her to reminisce. “I used to hang out with them all actually, when I was modelling. Britpop, Blur, Oasis, God, the parties. But then, of course, Common People came out, and everybody thought it was written about me, which was completely mortifying and ridiculous. I mean I barely knew Jarvis.” The two beautiful boys share a conspiratorial smile, the sort of conspiracy you can make when you realise just how ludicrous it is that you’ve found yourself where you are. She continues “but she came Greece. She had a thirst for knowledge. It couldn’t have been me. I’ve never wanted to know anything.”

It’s a standout line, evocative of the kind of listless, benign neglect embodied by the rich aristocratic family whose country pile, Saltburn, gives the film its name, Saltburn, a black satire written and directed by Emerald Fennell that’s been called “the most divisive film of the year”, with good reason. The family aren’t just rich, of course. They’re what my dad would call poshos, that strange sliver of the upper class who balance their inherited wealth and natural conservatism with a certain louche, even bohemian attitude, the sort of rich people whose jumpers may have holes and whose Volvos may smell of wet dog, but whom any Englishman worth his salt can recognise as wealthy, powerful and ennobled from 100 yards. Their undisciplined children fill the public schools of England, their unfaithful husbands fill the boardrooms of the City, their untalented wives fill the galleries of Mayfair, their unconscious parents fill the House of Lords. They are cunts, utter, reckless, moronic cunts, to the last drop. Yet they retain a stranglehold on Britain’s land, culture and imagination, both literally through their power and possession, but also figuratively through their dominance of education and the arts.

Hardly surprising, then, that a film set in their milieu of Oxford University and the country estate, a film that claims to highlight their entitlement and stupidity, would generate such divergent opinions, especially coming at the end of another generation of Tory rule. Saltburn is a long way from Common People, however. Other critics have compared the film to Evelyn Waugh’s 1945 novel Brideshead Revisited, which isn’t an enormous leap to make. After all, the basic plotline is similar, at least to begin; the lower-class protagonist [Oliver Quick/Charles Ryder] arrives at Oxford, ready to study and ignorant to the ways of the ruling elite, but soon finds himself transfixed by the boyish scion of a noble family [Felix Catton/Sebastian Flyte]. Becoming friends, or perhaps more than friends, the rebellious heir invites the young man to his family estate [Saltburn/Brideshead], where he charms the boy’s mother and sister, before finding himself in past his depth.

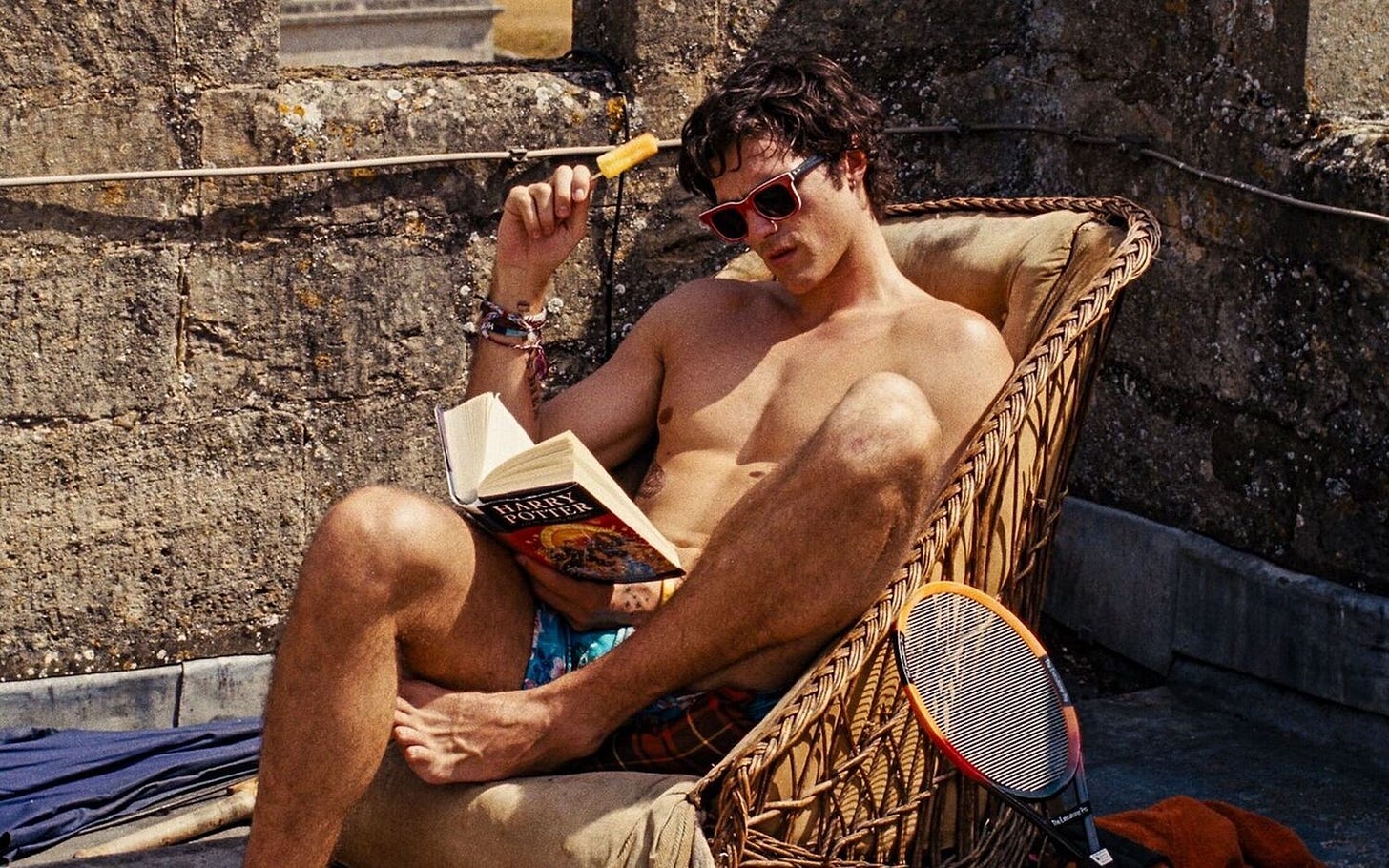

Jeremy Irons, Anthony Andrews and Julia Quick in the 1981 TV adaptation of Brideshead Revisted.

Brideshead is often regarded as Waugh’s masterpiece. Like Saltburn, it has long been a favourite of an English middle class keen to look in on how the other half live, and to pruriently observe their sinning. Similarly, like Saltburn, it’s provided a strangely alluring model for the rich and aspiring rich to live up to. It’s notable that a TV adaptation of Brideshead become a point of obsession for many students arriving at Oxford in the early 1980s, at the start of the Thatcher administration, a generation of students who grew up to become the most recent generation of Tory rulers. David Cameron, now Baron Cameron, recalled that “these were also the years after the ITV adaptation of Brideshead Revisited, when quite a few of us were carried away by the fantasy of an Evelyn Waugh-like Oxford existence.”

It’s not just half a plot that Saltburn shares with Brideshead, but a narrative device too. Both employ the technique of using a queer man (in the old-new sense of the word), and specifically a queer man of a lower class status, as a narrator and audience surrogate. Like Brideshead, Saltburn starts with this character, speaking later in life, reminiscing about what had happened at the country house many years before. “I had been there before” says Charles Ryder at the end of the prologue, “I knew all about it”. He knew all about it and he was going to tell you. The queer man moving into a different socio-economic class has become a staple of English literature. He is our man on the inside. On account of his queerness, he is accustomed to passing, to shape-shifting, to moving through, just as Oliver Quick does in Saltburn. Quick, you see. Ryder.

The queer looks. They learn about the rules, the eccentricities, the hypocrisies with fresh eyes, figuring out what the rich are really like, and as they do, we do, along for the ride. It’s through his queer eyes, motivated at first by lust and then curiousity, his desire muted and hence safe, that we see them living. A straight working class boy chasing a posh girl would never work; the defences would already be up. But to the English upper class queerness is disarming, even charming. In Saltburn, Quick does little else but look; nosying around the family silver, staring from the window as Venetia walks the gardens at night, watching through the crack in the door while Felix wanks in the shared bathroom between their two rooms (an architectural idiosyncracy that Saltburn shares with Brideshead and, indeed, the Perlman’s family villa in Call Me By Your Name).

The bathroom shared by Elio and Oliver in Call Me By Your Name (2017)

It’s a literary technique employed by another gay, Oxford-educated novelist, Alan Hollinghurst, in his 2004 novel The Line of Beauty. His protagonist Nick, recently graduated, follows his straight boy college crush Toby back to his parents grand West London home where he meets the boy’s beautiful but mentally unstable sister Cat, and his rich but inattentive parents, Gerald and Rachel. Set in the early 1980s, Gerald has recently been elected as a Tory MP in Thatcher’s government, and through this device we get to see through the public image of a happy family into its real workings, only to find that behind the Conservative ideals of family values lies sexual infidelity, cruelty and hypocrisy. This illuminates Nick’s own complicated private life as he navigates how to live in Thatcher’s Britain as a young gay man during the AIDS crisis. Despite the apparent warm welcome, he soon finds out that, like with the Catton’s in Saltburn, the rich only ever make transitory and transactionary attachments to the poor. Oh, I should have told you: the protagonist’s full name name is Nick Guest. Guest. Quick. Ryder. Our boys are always just tourists, always just passing through.

Although Saltburn bears some obvious plot resemblances to Brideshead Revisited, I think this similarity is only skin deep. Brideshead Revisited, after all, is nothing if not a book of deep conviction. It’s a book Waugh wrote in the midst of the Second World War, where he was recovering for a few months from a training accident before heading to Bari, Italy, on an improbable secret mission for the Special Operations Executive to Yugoslavia to aid the communist leader Tito and his partisans. Improbable firstly because Waugh was a committed anti-communist, and secondly because, in 1930, he had converted to Catholicism. Brideshead is a deeply theological novel written with a nostalgia and care for the sort of “ordered” society and tradition it depicts, however imperfect that order was. It was also written out of commitment; that, amidst that society’s destruction under the rationalising, modernising influence of mechanised warfare, something still mattered. In Waugh’s case, what mattered was God’s grace, the ability to be brought back into a happy relation with His creation even after all the chaos and sin and cruelty of both Waugh’s and Ryder’s earlier life. And sin there had been; as well as being divorced before his conversion, later necessitating an annulment from the Church before he could be remarried, he had been, like Ryder and Quick, a queer while at Oxford. Like both characters, he had come from a resolutely middle class background, and likewise he had fallen in love with a posho, Alistair Graham, and would spend his holidays at Graham’s stately home, Barford House, complete with glamorous mother and absent father (dead). Waugh’s own experience being an influence on Brideshead is hardly a secret: in the original manuscript Waugh occasionally slips up and refers to Sebastian as Alistair. Like I said, and unusually for Waugh up to this point in his career, its a deeply committed and sincere novel.

Evelyn Waugh relaxing as an older man

Conviction and sincerity are hardly words one could use to describe Saltburn. In The Guardian critic Adrian Horton suggests, convincingly, that it’s a vibes-based film, and “the vibes are lazy”. There is a visual coherence to the film, a sort of posho-gothic carried in the clash of bold and muted colours and sunshine and darkness; a fitting visual language for an old house in high summer. This vibe is boosted by some truly striking scenes which ride its back, including the red, grief-bottled breakfast, or the gravefucking. These scenes carry a plot that slowly reveals the mildly dissolute, fun-loving lives of young, rich, attractive party animals who reject meaningful connections with outsiders, or even each other. There are relationships, sure, but not really passion, more commitment to the vibe, the party, and when your money runs out, your time is up and you’re off the ride. It’s hardly the stuff of Brideshead, with its emphasis on the importance of lingering affections and the long-term damage of interpersonal cruelty.

A more pertinent comparison for Saltburn in terms of form and ideology might instead be Waugh’s 1930 satire, Vile Bodies. Written on the cusp of his conversion (driven, he claimed, by Olivia Plunkett Greene, a fellow free-wheeling party animal whom he lusted unhappily and who “bullied me into the Church”) and during the breakdown of his marriage to his first wife (also called Evelyn), the novel is a deeply pessimistic, cynical satire on the Bright Young Things, a social set of English aesthetes, aristocrats and artists who, mostly too young to have seen the First World War, threw themselves into the outrageous fun and thrills of modernity in the decade that followed it. It was shocking to those who had seen the horror and slaughter of the trenches that the sacrifice of their generation was for this: hollow, artless, debauched, disgusting fun. For those, like Waugh, who took part in the fun, there was clearly an attempt to escape the unmanageable expectations and resentments that came with victory.

Vile Bodies is extremely well-observed — virtually a roman à clef of his own social circle, a least in its dramatis personae — and bitingly funny, but at its core is the sense of disgust borne of someone growing out of the vibe, the excitement both of partying and of the thrilling new modernity. “Oh Nina, what a lot of parties” laments Adam, the protagonist, exhausted by Russian parties and naked parties, boring parties and drunk parties, Oxford parties and swimming pool parties and disgusting dances in Paris — “all that succession and repetition of massed humanity … Those vile bodies”. Same with Saltburn: all that period fingering, all that coke and Bolly, cum-slurping, succubus rape, karaoke-wailing, all those vile bodies… but where does it all end? What does it mean? The vibe, the scene and the shock seem only in service of themselves: at what point do any of these scenes break into a meaning beyond the plot?

Cecil Beaton’s photo of some of the actual Bright Young Things

For Waugh, it ends in destruction, and I can’t blame him. In my own first two books, themselves both satires on London’s late-capitalist (I hope!) faggotry, there seems nowhere for the story to go but the end of the world. It’s a get-out, a trick. The epilogue of Vile Bodies ends on “a splintered tree stump in the biggest battlefield in the history of the world”, stricken with biological weapons. But — and here’s the problem — Waugh’s apocalypse is the moment in which his cynicism is weaponised, where it sharpens to a point. This “circling typhoon” of decadence, of disconnection, of modernity, leads inevitably to a war of the worlds. Yes, it’s crypto-fascist, but it is a point, a value judgement. But here, circling too, is the fatal flaw in Saltburn. The world of Saltburn, its ancestral line, ends. But there is no reason that anything happens. What is the point?

This isn’t an argument for a didactic political lesson (personally, I wouldn’t mind, but that’s not everyone’s vibe). Rather, it’s pointing out that there’s no emotional component that moves the action; whereas Vile Bodies breakdown of weak social bonds drives towards calamity, Saltburn instead dissipates towards nihilism. Waugh’s destruction is the story, Fennell’s is just the plot. Throughout the first two-thirds of the film, enough is left unspoken to allow the viewer to build a universe of potential causes and effects which makes it feel, for a moment, like a very rich film. What makes the bathwater cum so delicious to him? When Oliver finally sticks his dick in the freshly-turned sod in which Felix lies, I gripped my hands into fists with a pure, disgusting pleasure at the weirdness of it all. There appears, for a moment, to be something unplaceably strange driving this man. And yet, from this point on, the film is suddenly lost. Any story is ripped from the viewer. In quick succession the rest of the family are knocked off as mere plot points, sucking the tension from the plot. Perhaps it’s counterintuitive, but one murder is far more unnerving than four murders. And then, in the final act, the protagonist becomes a Scooby-Doo-ass villain, ripping off his mask and explaining just how he did get away with it, despite all the pesky kids. Oh great, I thought, as a montage of sabotage made everything previously unspoken suddenly painfully explicit. This director thinks I’m a fucking moron.

So did Quick fuck Venetia to hurt Felix? Did he hope, in imbibing Felix’s salty, cum-laced bathwater, to ingest some of his superior, noble DNA into his own body? Was he, like Highsmith’s Ripley, aroused not by knowing humans, but by defrauding them? Was he disgusted by his own class, or did he desire to wreak revenge upon the rich in the mansions in which they live? Did he start by wanting a simple homosexual love affair, but become entangled in his own lies to the point where murder was inevitable, even just? Feeling Felix slip from his grasp, did he kill him so no-one else could have him, a mirror of the sort of fucked-up patriarchal urge that sees bankrupt men burn down their homes and murder their families? All were delicious possibilities before we were told, in bold print, ass hanging out, that no, this is what he did and he did it because he simply wanted the house. It was a simple murder plot from the first minute of the film. We’ll ignore the plot holes; how suicide seems fundamentally out of character for the rambunctious, easy-going father; possible, of course, but not so likely as to be part of any pre-determined masterplan; or how a person driven by a total, character-eradicating psychopathy is simultaneously driven to wailing grave abuse.

In the end, we are left with only one feasible place to look for a motive that drives the plot. It can’t be emotion, and desire seems pretty much out of the window considering Quick’s masterplan is in action long before the lingering money shots of Felix’s elongated, erect neck. The only real source is the thing Oliver lies about, runs from, obsesses over: his class. Oliver’s upbringing, far from the life of poverty and addiction that he describes, is actually very comfortably upper middle-class, albeit in an area that suffers from high crime and that ranks as one of the most deprived boroughs in England. Sitting between these two positions, as a well-off scouser, he becomes very specifically the supposed surrogate of an audience of a film who are, in all likelihood, from a similar background: neither powerful nor impoverished. So, who are we supposed to be?

One of the alternative covers for Pulp’s album “Different Class”

What is the attitude towards class in this film whose engine runs on the English obsession with class? The English, as is well known, have a complex attitude to class. We have an ear for it, the way one might have an ear for music. Its signals resonate to us, especially for the middle classes, for whom a constantly regenerating set of signifiers betray a very specific class position; a Waitrose shopping bag, a confused “was” with “were”, a dinner or a tea, a signet ring: all hum a recognisable tune, so much so that the signifiers themselves can be taken on or off almost as a costume. They are what Owen Hatherley describes as the “epiphenomena of class usually obsessed over by marketers, psychologists, and rock musicians”. That fancy dress is especially popular when young people attend university, searching to find an identity that fits and distinguishes them from the dreaded label of being middle class. English universities are full of people using their miner grandfather to offset their stockbroker grandfather, or, less frequently, hiding their humbler origins and accents, which is why Oliver’s lie is such a convincing and engaging plot point for an English audience. Being able to pinpoint or obfuscate exactly where you sit within a shifting class system is a defining characteristic of the English middle classes, and is an characteristic far more enduring than mere shopping loyalties. In the words of David Hoyle, “I am actually from a lower middle-class situation - and they are the most treacherous. You’re walking a very fine line to prove that you are superior to the truly poor… a lot of these middle class people will cut a ha’penny in two.” I, like Hoyle, am from a lower middle class situation; while my parents were frequently broke, we were never poor. An important distinction.

Yet the epiphenomena of class — the accents and shopping habits and dinner times — are not what makes class, even in England. As Pulp demonstrate in Common People, even if you adopt all the signifiers of a different class, “you will never understand / how it feels to live your life / with no meaning or control” because the actual phenomena of class — poverty and opportunity, limitation and reassurance — are its actual meaningful consequences. If you called your dad he could stop it all. The power of Common People, Hatherley astutely notes, is not just in mocking the upper class tourist slumming it with the poor, but in offering hope and speaking to the weird working class kids “who don’t play pool or smoke fags, who don’t talk in Cockney or Manc accents, who might be uninterested in sports or pints, who might not even be heterosexual — to tell them that none of this had anything to do with social class.” It’s not the sportswear that makes you working class, it’s that you’ll always understand, and that your dad couldn’t stop it all.

Saltburn does just the opposite. In its world, there is no meaningful distinction in the way our class influences our relationships with others. We are all willing to treat each other like property, we are all willing to laugh at our friends when their backs are turned, we are all liars. The only real difference between Oliver and the Cattons is envy. We are all just temporarily embarrassed Cattons. What makes Oliver an antihero within the film? It’s that he fills that strange archetype so loved by the English, the class tourist, enabled by his queerness. It’s only the intoxicating and ultimately toxic combination of intelligence and faggotry that has sheared him from his rightful class position and fired him into the echelons of the rich, and he’s here to report back to us that, underneath their clothes, they’re just the same as us. It’s all just epiphenomena, all the way down. And if they’re just the same as us, well, what’s the point in getting rid of them?

‘Utopian Drivel’ is written by me, Huw Lemmey. If you’re a paid subscriber, thank you so much for your support. Please do forward this to anyone who might enjoy it.

If you aren’t a paid subscriber, please consider subscribing; paid subscribers also help support pieces for free subscribers!

You also get access to the entire archive of 100+ essays, including posts such as this piece on the idea of a gay audience, this short story about breaking glass, , this essay on depression through a mirror, darkly, and this report on watching the Queen’s funeral at a gay sauna. Free subscribers get occasional posts, like this guided walking tour around London’s world of queer espionage, or this double-header on the Gay History of Private Eye magazine.

Share this post