I write regular essays on everything from gay sex to Romanesque architecture, from Joan Didion to Francisco Franco, from grief to murder. If you would like to get regular essays from me direct to your inbox, please consider subscribing. For this week only I’m offering 20% off for a year’s subscription, meaning you pay $4 a month or $40 for a year’s worth! A steal…

It’s said that the representation of queer people on television has been revolutionised over the past ten or twenty years. But has it? While it’s true that there are more openly queer people on TV than ever before, how has their presence in otherwise straight storylines changed the way queer stories are told? Are we seeing more queer experience on television — or are we just getting gay stories for straight allies?

Let’s say my teenage years were the turn of the century, for drama’s sake. I’m sure I’ve told this sob story before, but life was hard for a teenage fag in the early noughties. I was the only gay kid in school, and my mum was very sick, and my memories are built around a scaffolding of emotions that overwhelm the facts, mainly revolving around the idea of getting out, of escaping. I wasn’t even a particularly rebellious teenage fag, just a morose one, going home from the ‘60s comprehensive classrooms with their pinboards and carpet tiles to a tangle of medical equipment and healthcare workers. At the weekend, though, I could escape, through a miracle of serendipity. When I was a very little kid, you see, I lived in a long, low valley that was sparsely populated. As a very small child a new family moved in as our nearest neighbours, a mile away. They had a son, a month older than myself, and we became friends. My family moved away, but not so far; we went to different schools but hung out a lot, most weekends, and as a teenager, that was the escape.

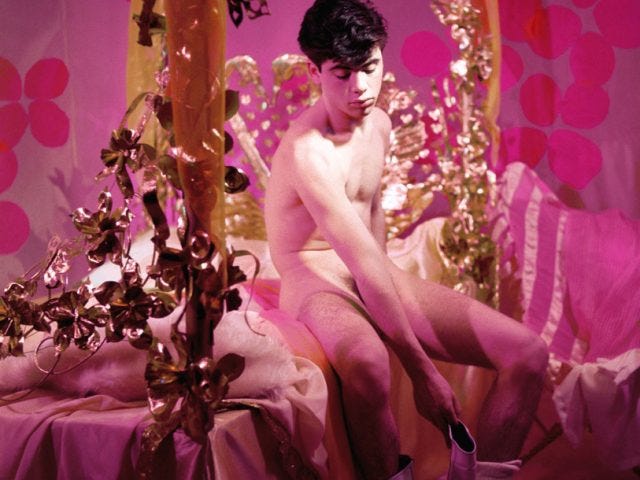

The serendipity was the interests of my friend’s mother, who cultivated a library of incredible movies. I’m trying to think what I saw at the cinema around that age: Armageddon, various iterations of Austin Powers, Bridget Jones’ Diary and Jackass. At their house I saw Nosferatu, David Lynch, Muriel’s Wedding and, more influential than anything else, queer movies, like My Beautiful Launderette and Velvet Goldmine, A Beautiful Thing,Priscilla, lost greats like James Bidgood’s Pink Narcissus, at that point only just rereleased, some Bruce LaBruce and, divine providence, most of John Waters. Today it’s harder to make clear what, pre-social media, seemed so obvious; you don’t really stumble upon queer culture, you are actively inducted into it.

My friend’s place also had satellite TV, which we had never had. There was a forbidden taste there of a brash, quick-cut, American, MTV-style of television that was alien, sometimes even a little scary, to someone raised largely on the BBC, Channel 4 sometimes, and ITV for Heartbeat and Corrie. One of the shows my friends loved was screened on Bravo. In it, five different iterations of faggotry took a puppy-dumb heterosexual man and just pulled him apart for his flaws. It was 2003; Bush had declared it was MISSION ACCOMPLISHED in Iraq, I was wearing a Che Guevara t-shirt I bought mail-order from the back of Kerrang! and sat in front of the TV, stoned from bad hash and eating cheetos, I was being assaulted with a type of queer culture I’d never experienced before on TV. It was called Queer Eye for the Straight Guy.

That period, from late nineties to early noughties, had been a crux period for gay men on TV. While representations of gays were still largely homophobic, even on youth-oriented shows like Friends, there were emerging gay stars and plots where they weren’t solely the butt of the joke. So Graham Norton leaned into butt-fucking jokes that were owned by gays, and Will and Grace embraced the nascent status anxiety of not-like-the-other-gays, a meaningful representation not to be dismissed. Queer as Folk was explosively sexy, inducing a whole generation of young queers to sit far too close to the TV with the sound all the way down after their parents had gone to bed, one hand on the off switch and the other on their cocks. But somehow the most disruptive for me was this low-budget lifestyle show on Bravo.

There was an almost anarchistic intensity to Queer Eye for the Straight Guy at times; the way the ‘Fab Five’ burst into the house of a heterosexual who may as well have been expecting the drug squad, and who only ever looked half-persuaded that their appearance on the show was a good idea. But more than that, there was the feeling that QEftSG, with its how-the-other-half-live exposé of heterosexual male habits and its aggressive sense of near-disgust at them, was somehow a show decisively aimed at gay men. As a fucked up teen battling with self-hatred, it wasn’t always easy; Carson Kressley’s intensely queer, lascivious, sexual and slightly femme charisma scared me, maybe even disgusted me at the time. His refusal to be otherwise was destabilising, an indictment of my willingness to conform. But it was a show for a queer audience, in which we were the heroes and the straight men were somehow the rejects, the ones failing at life. It seemed to be by us, for us, inverting some of the social shame around our own private lives and asking, instead, what if they were the hopeless cases who aspired to what we have?

I’ve been thinking of the show because of a comment from Sarah Schulman on an excellent recent episode of the podcast Suite (212). In the show, which discussed the cultural impact of the ongoing AIDS crisis, the guests were talking about one of the most significant mainstream representations of that crisis in the US that appeared on screen, the HBO adaptation of Tony Kushner’s 1991 play Angels in America. The show was a lodestone in the cultural representation of AIDS and its effect on gay men, a moving and elegiac attempt to capture the terror that a HIV diagnosis could wreak upon gay men and their lovers before the development of effective antiretrovirals. In fact, its iconic status means that for many people, including queer people, the play is how you learn about the crisis at that time and place, which was used to great effect in the recent Netflix adaptation of Tales of the City. In the show an older character, furious at a younger gay man’s claim that he understands what is was like for gay men at the time, snaps back “Oh you do? Really? Because you saw Angels in America? Fuck that. Fuck that. You have no idea.”

Much of Schulman’s criticism on the limits of the play, on the faultlines of representation, is both incisive and generous, as we have come to expect from the New York writer, but one comment really stuck out for me. Like films such as Philadelphia and The Dallas Buyers Club, she says, the plot revolves around:

the gay person who’s alone, and they’re dependent on a homophobic straight person to heroically overcome their prejudices to help them. So Angels in America occurred at a time when people with AIDS and gay people with AIDS were abandoned by their families, by their government, by their society, and joined together to force the country to change. But Angels in America doesn't show that. It shows gay people betraying each other, and abandoning each other, and the Reaganite Mormon straight person heroically going through a change, and that was a very palatable story… what these works all do is they erase the gay community and the gay political movement that actually was creating the change. They show gay people abandoning each other instead of straight people abandoning them, and then they get enormous amounts of approval.

I was profoundly moved the first time I watched Angels in America. And perhaps the only way a wider straight audience could grasp the intensity and scale of the abandonment was for them not to perceive it as an accusation. The moral enormity of the subject makes that a difficult call for a playwright to make, and perhaps in communicating the enormity he erased the importance of making the accusation. I say that not to accuse Kushner, but because it provides a useful framework for thinking about what has followed. What if, following Schulman, the successful emergence of queer figures and queer culture into the wider mainstream has only been possible by removing the problem of the heterosexual.

What I liked about QEftSG was, for all its myriad failures, its problematic jokes (I haven’t watched back but I’m certain they’ll be in there) and its relentless aspirational consumerism, its whiteness, it did at least acknowledge the problem of the heterosexual. It acknowledged that amongst gay people, between us, straight people are a problem, and that queer people in general, enjoying hanging out with each other, have a culture that does not revolve around the figure of the heterosexual. Most early manifestations of queer culture breaking through to the mainstream in fact understood that, and focused on intra-queer dynamics. Queer as Folk was about gays; its storylines were about gays wanting to fuck other gays, or not. There were no straight men really in Will and Grace, and the complex friendship between two different modes of being a gay man was central to the plot. Perhaps this sounds stupid, but The L Word was made for lesbians to watch. In Tales of the City the gay characters drank at gay bars, went to gay saunas, and had gay sex. Even in the notoriously homophobic Friends, when Ross’ ex-wife became a lesbian, well, she became a lesbian, and put away childish heterosexual things.

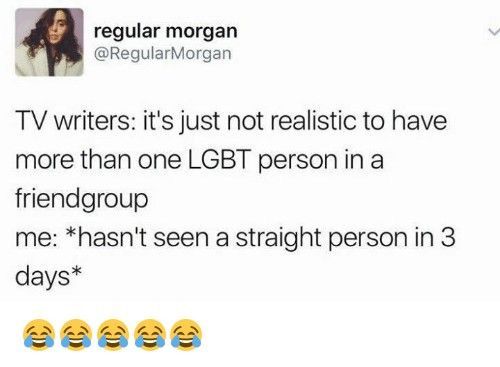

Seeing a queer person on screen has become more palatable to a straight audience (Generally this means a gay man, occasionally a lesbian, rarely a bisexual, and trans representation is a horrific nightmare all of its own, such that I won’t focus on it in this essay, but instead point you towards the Laverne Cox and Sam Feder film Disclosure.) For many, this represents progress. Perhaps it is, but the price of that representation has been, in my opinion, a shift away from the context in which gay life is portrayed. A gay person is acceptable on primetime television, but as an adjunct to the heterosexual story; their issues, such as they are portrayed, are increasingly seen as moral thought experiments on which the straight characters can dwell, or even just as a signifier that the heterosexual characters are liberal and open-minded enough to have gay friends. But the depiction of queer lives operating independently of the heterosexual, of queers who have aspects of their lives that don’t concern the heterosexual, or a culture that acknowledges the problem of the heterosexual, are few and far between. A viral tweet a few years ago put it more succinctly:

TV writers: it's just not realistic to have more than one LGBT person in a friendgroup

me: *hasn't seen a straight person in 3 days*

While there are more individual gays on screen than ever, the absence of life as it exists between queers is almost more pronounced today than it was twenty years ago. Short of Pose, an historical drama set in the early nineties, and Tales of the City, a sequel to a show first broadcast at the same time, I’m not sure I can think of a single show like Queer as Folk or The L Word which portrays such a culture. The issues that face LGBTQ people are almost entirely gone from our screens, except from when, as Schulman points out, they are intensely personal, stripped from the political, and provide an opportunity for growth for a heterosexual. The trials of coming out are in, the trials of finding a job or apartment when faced with homophobic bosses and landlords is out, learning to love yourself is in, learning to find one remaining bar still open in this damn town where I can get a cold beer and a blowjob is out, a gay best friend who seems to have no other gay friends is in, access to fucking healthcare or an appointment at the gender identity clinic is out.

A case in point: I settled down to watch Happiest Season just before Christmas, a much-awaited lesbian rom-com starring Kristen Stewart, Aubrey Plaza and Alison Brie, and celebrated before release as a progressive step forward in mainstream lesbian representation. Kristen Stewart plays a young lesbian woman going to spend Christmas with her girlfriend’s family, who she’s not yet met. Only one problem: her girlfriend hasn’t come out yet. Uh oh! From such promising beginnings, the film curiously fails to build momentum. The premise might suggest the heartwarming comedy of errors and manners we saw in The Birdcage when a gay person’s daily life meets a straight person’s expectation of what a family should look like. Instead we get an increasingly vicious and unhinged renunciation of love and homosexuality from Stewart’s girlfriend, wildly disproportionate to the supposed conservatism of the family.

Her girlfriend’s cruelty only serves one function; to increase the good vibes festive payoff when the family, in the end, welcome Stewart into the fold. I wonder what a heterosexual might make of this film; as a fag, the intense and visceral cruelty of the girlfriend, disavowing not just her lover but lesbianism per se in a virulently homophobic manner, is far too disturbing to be “made good” by the cosy acceptance at the end. While the unbroken integrity of the family unit might cover that sin for a straight person, it surely stirs the pot of the queer psyche too much for anyone to believe that Stewart, having being treated as a source of humiliation and shame, would stick with her terrible girlfriend? The compulsion to stay with your appalling partner through their increasingly ill treatment of you, because, I don’t know, love finds a way, because the lure of the family: this is a heterosexual’s love story. I struggle to believe that any queer watching Happiest Season could regard it as a happy ending; the girlfriend’s unresolved homophobia is bound to destroy the relationship in the end. It seemed all too clear that, despite the lesbian director and bisexual star, the film was part of this new genre: gay stories for straight allies.

Of course, the use of a queer person as an audience surrogate is nothing new, but that feels different. The external eye that a queer character, especially a narrator, can bring to a story can be used to help explain the dynamics of an otherwise closed society from the perspective of someone who might pass, but nonetheless is chronicling and analysing with the eye of the queer, watching for dangers and idiosyncrasies. In Brideshead Revisited, a novel by Evelyn Waugh adapted for TV in 1981, Charles Ryder plays theexemplar of the queer audience surrogate. His sexuality lets him through the gates of Brideshead, allowing him to explain and decode from the inside, to the outside, the vagaries of upper class morals and priorities. Christopher Isherwood plays a similar trick in Goodbye to Berlin; the homosexual is somehow outside of the class system and marriage market just enough to look in, in his words as “a camera with its shutter open, quite passive, recording, not thinking.” Lesbian author Patricia Highsmith’s stunning character of Tom Ripley, a sociopathic fag par excellence, allows him and the reader to move effortlessly through the class dynamics of the rich leaving bodies in our wake, and in The Line of Beauty gay author Alan Hollinghurst provides a cognizant riff on the theme, with the protagonist Nick Guest (guest, geddit?) slipping between the heights of the wealthy Thatcherite elite and the working class gay lives they were maligning and destroying. But all of these characters perform a similar function; observing from the outside a social circle relentlessly obsessed with itself, blind to the existence of the different, the other. They are our mole on the inside, and they allow the reader to see it with the fresh eyes of a queer who can never belong. “What the fuck,” you end up thinking, “are these people doing?”

This is fundamentally different to gay stories for straight allies. Within all of those stories, it’s conceivable that the queer view of heterosexuality might make an accusation of misdeed or oddness in which the heterosexual reader is complicit. But in the gay story for the straight ally, there is always a more pressing concern: to make the good heterosexual feel included. While it may be in some way important to “see yourself on screen”, what good is it if you don’t see yourself within the context of a wider queer culture, if the purpose of your story as a queer person is solely to confer some moral benefit, to offer a fable, for a straight life? It feels like, as queer individuals are ever more present on our screens, actual queer stories are increasingly absent. Mainstream manifestations like RuPaul’s Drag Race feel more like an outreach project for straight people, offering an exciting chance for people to watch competitive TV without having to endure heterosexual men, than anything that speaks to and for queer people. Even the more specific stories of gay life that slipped through in earlier seasons, testimonies against shame, or even the rare invocation of queer solidarity, seem to be replaced with a series of self-help mantras based on personal growth and self-realisation.

Which brings us back Queer Eye for the Straight Guy. After two seasons, the show abbreviated itself as simply Queer Eye, losing the important dialectic that drove the engine of faggotry at its inception. Cancelled after four years, the show was resurrected in 2018, and the differences between the two versions seem to illustrate both the marked increase in visibility of queer people (the new show being marketed as a huge Netflix production) but also the change in the function of queer community and stories on television. Gone is the antagonism between the lifestyles of the feckless straight and the functioning queers, a dynamic that seemed to overturn supposed heterosexual superiority. Gone is the spirit of an unleashed, even unhinged sexual libertinism, a sexuality that potentially scared the straights. Instead, the queer is a combination of a nurturing, positive cool mom, not like the other moms, and a cheerleader whose own life stories and struggles against the odds help to guide a heterosexual through to a better you. “Ask not what you can do for your queer, but ask what your queer can do for you,” it seems to say, leaving unspoken the real nature and social context of traumas, traumas that are only ever hinted at as signs that these things too shall pass.

Yet those hints point to issues of lives that are perhaps uniquely and explicitly queer, from Bobby’s visible trauma from a childhood raised as a gay man within a Christian Fundamentalist tradition, to Antoni’s complex and unresolved familial issues, to Tan’s frequent references to childhood ostracisation for being queer. These issues are never discussed between queer people either on Queer Eye or, to be honest, on TV more generally. A notable exception might be Pose, but Ryan Murphy has followed that show up with Hollywood, which instrumentalises experiences of racism and homophobia to tell the feelgood story of a straight America that overcomes its prejudices so flagrantly that its finale is unwatchable to an Aaron Sorkin degree. There is a wider awareness than ever amongst “allies” that coming out, or gender dysphoria, or queerbashing, might be traumatic experiences for queer people, but where are they discussed between queer people, and not simply as a hook on which to hang a narrative of redemption or anti-discrimination for the cisgendered or heterosexual?

A recent commissioning brief I read for a broadcasting opportunity that claimed to be “for and about LGBTQ+ communities” included the following paragraph, which I include here not to pick on them but because I think it sheds a light on one of the reasons for this subtle shift. “Queer perspectives are central to popular entertainment and learning,” it began. “What is key to their success is not only reflecting these characters and issues authentically, but creating a space for a broader audience to engage with the world seen through a Queer lens.” What if the things queer people need to say to each other, the things that we say amongst ourselves, don’t create a space for a broader audience? What if the very point of queer culture is the exclusion of the figure of the heterosexual? What if the things queer people want and need to say and hear with each other are things that straight people might find challenging, unfair, accusatory?

These queer stories for straight allies appear on the face of it to be acts of representation for queer people. But if the stories are always told with one eye on a potential straight audience, always hoping to snag a little of that market share, to sprinkle a little of that charismatic queer pixie dust on the heterosexuals, to make them feel a little better, a little more included, a little more fabulous, are those stories actually queer stories? Where do we go for queer stories for queer people?

‘utopian drivel’ is a weekly essay series by Huw Lemmey. Please feel free to share and forward today’s newsletter with anyone who might be interested. For those just visiting, I send out a newsletter/podcast (about) once a week to paying subscribers — for less than $5 a month — and once a month for free subscribers. You can subscribe here, and, if you like it, please hit the like button. It helps other people find my newsletter.

Share this post