This is the second part of a two-part essay on spiritualism, grief, freedom and politics. Part one can be found here.

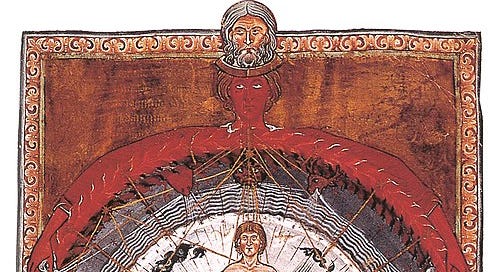

"Universal Man" illumination from Hildegard's Liber Divinorum Operum, I.2. Lucca, MS 1942, early 13th-century copy.

The relationship between a revealed truth and a woman recovering from sickness has some analogies in the mystical experiences of the 12th century nun Hildegard von Bingen, who, pledged to a religious life at a young age and in the care of the anchorite Jutta von Sponheim, had experienced visions that were revealed to her. She refused to acknowledge the visions, however, until she was struck down with severe health problems and sickness. Following her recovery from the sickness, which she perceived to be a result of denying God’s direct message to her, she began to write them down.

These works include Scivias, which contains her complex revealed cosmology and visions on the nature of both the human and the Church, but also Liber Divinorum Operum (The Book of Divine Works), which produces a wider view of the relationship between the human and the universe, and their interconnectedness, through the use of allegorical figures of women, who are consistently centred within Hildegard’s writings (her medical writings include the first known written description of the female orgasm from a woman’s perspective). While these works are mystical—produced from a direct connection with the divine—rather than spiritual—produced from a message from the dead—Hildegard’s relationship between sickness and revelation gave her worldly teaching a potency which challenged (and sometimes reinforced) the political and ecclesiastical establishment of her time through the same mechanism: namely, that these messages are delivered, regardless of the messenger:

“The marvels of God are not brought forth from one's self. Rather, it is more like a chord, a sound that is played. The tone does not come out of the chord itself, but rather, through the touch of the Musician. I am, of course, the lyre and harp of God's kindness.”

McKee’s suggestion is that the same mechanism helped spread radical political positions through spiritualism as the religious movement travelled. He refers to Allan Kardec, a French author and scientist who became interested in seances in his 50s, in the 1850s, when the phenomenon was beginning to spread. He produced a series of books which formalised his beliefs into something like a syncretic religion, bringing together Christian theology with spiritualism and pseudo-science into a philosophy he called “Spiritism,” a monotheism which posits that reincarnation is real, and that spirits can interact with the living world. Both Spiritism and spiritualism spread through Spain and Latin America; the Puerto Rican anarchist and feminist Luisa Capitello, who rejected the Catholic Church, nonetheless embraced Spiritism as not only compatible with anarchism, but as a companion to it—although she criticised the same tendencies towards injustice and inaction in the Spiritists as she saw in Catholicism.

Capitello’s Spiritism is unsurprising; syncretic religions based around spirits existed on the island long before the importation of Spiritism, as they do across Latin America, and anarchists already held an opposition to Catholic dogma and rituals like baptism and marriage. Many syncretic religions in Latin America derive from a blending of Catholicism with traditional religious beliefs held by indigenous people and by African slaves transported to plantations in the Americas, both of whom were forcibly converted to Catholicism. Spiritism itself is also now a component part in other syncretic religions, such as the Afro-Brazilian faith Umbanda or the Afro-Cuban faith Santería, which blends the Catholic veneration of saints with traditional indigenous practices, Yoruba traditions and Kardec-derived Cuban Spiritism.

The adoption of Spiritist beliefs by many anarchists in Catholic countries were a manifestation not of atheism but of anticlericalism, an important distinction which is sometimes lost in contemporary discussion where atheism, or even anti-theism, is the more prominent public face of the conflict between belief and disbelief. But Capitello’s beliefs are an example of the strong link between this particular brand of spiritual practice and anarcho-communist and feminist politics across Spanish-speaking countries in the 19th century, facilitated by the practice of mediumship and the prevalence of women as both mediums and converts.

Nowhere was this conjunction clearer than here in Catalonia, where republicanism, feminism, anti-statism and spiritism combined into a general atmosphere of radical free-thinking. The author and feminist Amalia Domingo Soler was also the editor of La Luz del Porvenir (The Light of the Future), a spiritist journal published in Barcelona at the end of the 19th Century, where she called for the secularisation of civil acts such as marriage, birth registration and burials, freedom of conscience and mutual aid between members of a ‘General Association for Freethinkers’. The anticlerical nature of Spiritism helped bring its originally middle-class demographic into closer contact with working-class republicans and anarchists; it goes without saying that the different factions are not coterminous, and the anarchists and spiritists disagreed especially on the use of violence, but links were still made and many belonged to both camps. At the First Annual Spiritist Congress, held in Barcelona in 1888, Huelbes Temprado declaimed from the stage:

“And moreover, spiritism, as you well know, is not only religious. It is complete, revolutionary, more revolutionary than all that is considered revolutionary in the world, because it includes them all. Pacific, yes; bloodless, that is true; yet spiritism's action in the spheres that existence embraces must be sweeping, overwhelming; we would like to smash this society and organize it again!”

The following year, less than two months after the end of the Cuban War of Independence, the third such liberation war the Cubans had fought against the Spanish state (during which an estimated 200,000 Cubans had died, mainly in concentration camps), anarchists, republicans and spiritists from across the world met again in Barcelona for the first meeting of the International Arbitration and Peace Association. According to the academic Gerard Horta:

“A crowd packed the hall to overflowing: the meeting called for the abolition of permanent armies, the establishment of arbitration to settle international conflicts peacefully, the constitution of a federation of free peoples in Europe for the harmonic development of all individual and collective interests. Moreover, the International League for Peace and Universal Brotherhood was created, ‘the most outstanding players were the anarchist and spiritist sectors’. The spiritists understood that the popular classes, ‘the great mass of labour,’ were the principal victims of the war, forced to act on behalf of the ambition of dominance and exploitation of the minorities that promoted the war.”

As the death of Van Dyke Fernald, two decades later, would prove, peace and universal brotherhood never arrived. Nonetheless, spiritualism remained. The belief in communicating with the dead is indeed the oldest road, and perhaps the craziest road of all, but the need to talk once more with those already gone, to come to terms with the wars and poverty of this mortal plane, is all too real. Josephine Fernald seems to have found little reason or help to deal with her grief in Kipling’s country; I find it fascinating how both her, Ascha Sprague and Luisa Capitello found within mediumship a new space to think thoughts, to discuss futures, that were otherwise unthinkable and unspeakable in the societies in which they lived.

For my subscribers:

Thank you as always for supporting my work. In other news, a new series of mine and Ben’s podcast Bad Gays, where we discuss bad and complicated gays through history within a wider social and cultural context, starts this Tuesday! I think this season is going to be better than the last, with some truly fascinating and malignant mollies featured. You can find it here, or wherever you catch your podcasts—just search “Bad Gays”.

If you enjoyed this essay, please feel free to forward it to anyone you think might be interested. If you were sent this essay by a friend, please consider subscribing for regular emails on everything from gay pride parades to satirical chamberpots to weird fiction about decrepit Radio 4 presenters: