(A quick note: this essay discusses racism, transphobia, homophobia, and violence.)

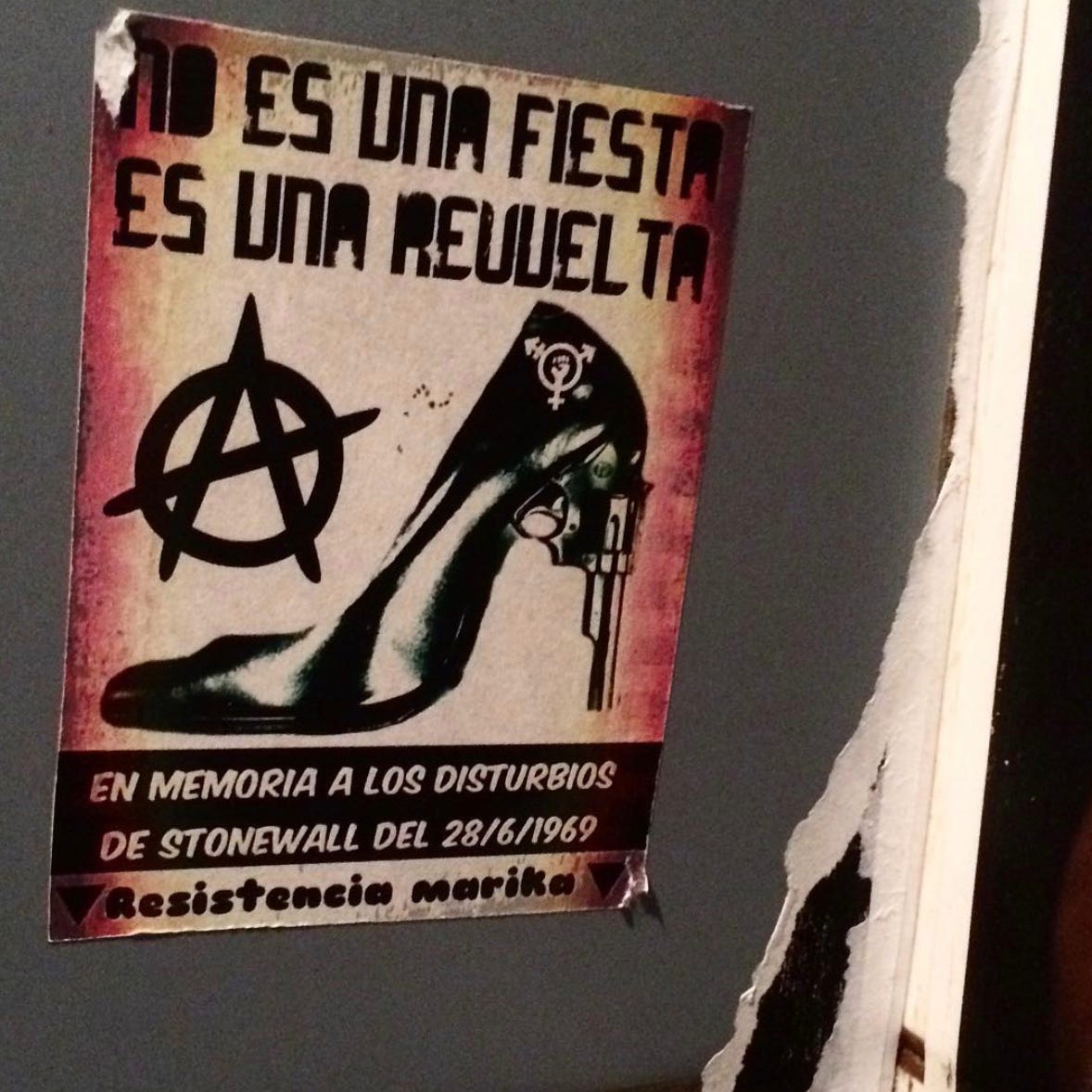

Last week I joined the Orgullo Critical (Critical Pride) march, an anti-corporate response to the money-infested business of modern Pride parades. The crowd was swollen with queers, their placards and flags addressing the rise of the far-right, confronting anti-trans politics and the violence of borders, as well as ongoing political struggles such as the Telepizza delivery drivers striking for a living wage. Here it was; the spirit of queer, angry rebellion as it manifested at the Stonewall Inn fifty years earlier, or at the 1977 Barcelona demonstration against the Ley de Peligrosidad y Rehabilitación Social, the Franco-era laws designed to repress homosexual and trans people. As we reached Plaça Catalunya, a section of the march surged towards the McDonald’s; within a minute there were scuffles with security as the demonstrators reached for the rollershutters, pulling them down and shutting down the restaurant. On the advert outside, someone graffitied “homòfobs”.

It wasn’t a token gesture against the multinational but an act of solidarity; in the same McDonald’s just two days earlier a young queer kid had been attacked by some macho prick who came after him for wearing short shorts, a strapped top and platforms. A security guard had stood nervously by as the two men — a tough-looking muscular man and a slight, camp man — faced off against each other. It was his appearance he took objection to, the sort of commonplace homophobia you still see coming from people who would claim otherwise not to have a problem with queers. The ‘shoving it down our throat’ you see referenced so often, a metaphor reserved exclusively for gay men. "This is a public place where there are children" he shouted at him. His visibly queer demeanour and dress was a challenge to the heterosexual domination of public space. He made a brave defence of his position, and his unexpected unwillingness to cede to this attempt to reassert heterosexual control of the space riled his aggressor, who threatened to punch him, to “make you heterosexual”. The mask slipped; the gay kid was an unignorable queer contaminant, and his refusal to be shamed for his gender presentation, his sexuality, was a direct challenge, an inversion of the shame he was expected to perform, turned into pride.

This is why I go on Pride marches. I can’t speak for anyone else, but for me, growing up gay meant growing up cloaked in shame. As I turned into a teenager I came out, and came out into an everyday life without queerness. I am the first gay person I ever met. For the rest of my teenage years, I was the only openly gay person in a comprehensive school of 750 students. Section 28 was still in force, although the atmosphere of hostility was less due to the law so much as the fact that many of the staff were bullies themselves. The corridors stank of petty authoritarian control, of aggression against not just the weak, but anyone not willing to take part in the culture of mockery. “Dance, coco pops!” the deputy head told one of the few mixed-race kids in the year. “You must submit to discipline in order to earn your freedom” we were told in assembly. It was grim and mean.

My gayness was referenced daily, in the usual ways, something that followed me round, and that I internalised as a stain or smell. I couldn’t escape the fact that everyone around me regarded me as disgusting. I was only just discovering what my sexuality was; not my sexual identity as “gay”, but what things excited me. Every time I saw something that aroused my curiosity — a muscle running along a forearm, the nape of the neck on a freshly cropped haircut — I was immediately and terribly aware that I could not be caught looking, that if I was, everyone else around me would regard me with disgust. That disgust showed itself in the corridor and the playground; my body was the target for tripping and spitting in the corridor, and kicked footballs or thrown punches outside. When another boy discovered (wrongly) that I desired him, he cornered me in the science block and slammed my head into the coathooks. Queuing outside the changing rooms, another boy asked me what gays do. When I refused to answer, he held me down on the worn blue carpet tiles and pretend humped me, rubbing himself against my arse. Everyone laughed to see me having to do what I enjoyed. His erection against my leg was funny, because I was disgusting.

We did have a sex education class about homosexuality, as it happens. In the first hour the teacher explained that some men are women trapped in male bodies, and they are called ‘homosexuals’ or ‘gays’. Everyone turned in their chair to watch and wait for my reaction. Then we watched the movie Philadelphia. We broke for break, then we came back and watched Tom Hanks die of Aids, because he was gay. After that, a lot of people either warned me about Aids, or hoped I got it. On the bus to Beamish Open Air Museum the guy in the seat behind me, whom I had been friends with from junior school, pointed his phone at me and made beeping sounds. “It’s a gaydar” he said. Everyone laughed. Then he told us that gay men eventually need to wear nappies because they get fucked in the bum so much. Eventually they shit out their insides. Everyone laughed, it was funny that I’d end up shitting myself from being fucked up the bum. I felt weird when I got home, and didn’t want to think about men’s bums any more.

I’m not telling you this to induce pity, or to blackmail you into listening dutifully to my feelings about homophobia. I’m just saying, that’s what it was like. It wasn’t very long ago, and I’m sure for plenty of kids that’s still what it’s like. For the first 5 or 6 years of my life, every time I thought about sex, I thought about how disgusting I was, how I was probably going to die, and how my body, with all its involuntary and powerful reactions to other men, was something like a smear of shit on a shirtsleeve. When I told a sympathetic teacher about the changing rooms, she told me I could go to the art block during my P.E. lessons from now on. The problem, clearly, was me; remove me from the situation and the temptation to humiliate and assault would be gone. Isolate the problem, and remove it from the heterosexual space. This was the heterosexual response to the queer outlier, it fucked me up, and I think about it every time I go on a Pride march.

There’s a scene in the 2014 film ‘Pride’ where Jonathan, a burnt-out former gay liberationist who has been roped in to supporting a group of younger gays and lesbians in their campaigning for striking miners, attends a disco in the union hall. The floor is filled only with the miners’ wives, with whom he dances. “This is a first, this — men on the dance floor” one of the women tells him, “Welsh men don’t dance...can’t move their hips!” He responds by asking the DJ to put on a disco track by Shirley & Company. He takes over the dance floor, drawing all eyes to himself; it’s a pivotal moment in the film, where the supposed shame falling on the gays and lesbians is passed over to the miners. Jonathan, lost in a paroxysm of dance, turns his queer body in the space into a weapon of his own liberation. He ceases to care about the judgemental views of the hyper-masculine men he’s surrounded by. In doing so, he offers his own former shame back up as a challenge to them: I’m not ashamed of what I can do with my body, are you? “Shame! Shame! Shame!” the track plays out across the crowded union hall to two young miners at the bar, “shame on you, if you can’t dance too!” They take up the challenge, and squeeze more joy from their lives.

Like the very word “queer”, shame can be hijacked by those it stigmatises, turned into a challenge. Many queer people have spent a lifetime checking their behaviours, certain expressions of themselves, fearful that there will be a “tell” to straight and cisgendered people waiting to judge them, or a provocation to violence. Pride marches are a public, collective rejection of the imposition of shame. On the third day of the Stonewall Riots Allen Ginsberg turned up to watch, and was struck by the physical change in the demeanour of the queer and trans rebels. “You know, the guys there were so beautiful,” he said as he walked away, “they’ve lost that wounded look that fags all had 10 years ago.” I can’t help but think about the shame I filled myself with when I’m with other queers en masse like that. I feel like I’m broadcasting back across time to myself, from this hot street full of skin and leather and glitter, back to a teenage boy thrusting his single gay magazine beneath his mattress. Maybe the slither of resistance I had back then was nurtured telepathically by this future man who must, even then, have been somewhere inside me, just as the scared boy still hides in me, changing the way I walk in a room full of straight men, flinching from my boyfriend’s touch on the nightbus. Because of course I still haven’t fully processed the shame. I work through it all the time, before the mirror in the changing room at the gym where I refuse to look away. I kill a little bit of it one hot afternoon with the shutters half-closed, kissing two strangers in their bed and not hating a moment. I write down some notes after waking in the early hours, finally putting two and two together about some incident two decades ago. But still it lingers.

I’ve had therapists say to me that many of our neuroses develop as pretty reasonable and effective defence mechanisms in times of danger, and simply outstay their welcome, lingering in our psyches when they’re no longer needed, poisoning us. The shame does that; it helped me pass through school and the parallel catastrophe of grief with a lid on my desires, unnoticed and holding myself correctly in front of the straights, and without falling into some fucked-up situation while lost and untethered. Thank you, shame. But you’ve had your time, and some more; I didn’t need to spend another decade or so in fear of human touch, running from the idea that anyone who found me attractive was playing a cruel prank, lying prone in my bed all afternoon hating myself for being depressed, and being depressed for hating myself.

Best to help others nip it in the bud for others. I hope that one function of Pride marches is still, as it always has been, an outreach programme, a recruitment drive. From its earliest days, Pride was a communication to other LGBTQ people. The photos in newspapers, the nightly news reports — they reached into suburban homes where homosexual or trans lives were barely recognised as even existing, bringing with them the siren call to closeted queer kids that we’re here, and we’re waiting for you to join us. They are a moment when all the behaviours that can still make us ashamed, that many of us still feel inside, can be owned in full view in heterosexual, cisgendered space, in the very streets where we often suppress ourselves. I hope that they broadcast across space as well as time. I hope this unplaceable and flawed solidarity still undermines some heterosexual, cisgendered family’s psychic domination. I hope for some kid, somewhere, we are still the worm in the wood, the rot at the root, the taint in the blood, the thorn in the foot.

That’s not all there is to Pride marches. The repression of queer people is not simply or solely an idiosyncratic sexual revulsion, but a thread within a fabric of social control and repression. It starts early, and cruelly, and its effects linger on in our bodies and in our sense of self; a quick change in marriage law doesn’t erase a sense of self borne in an environment of degradation. And our struggles don’t just co-exist with other fights for labour rights, for gender liberation, and for freedom of movement, but exist within them, are part of them. That’s why things like the beautiful and aggressive prominence of pro-trans messages at Pride in London this year were so important, as trans people across the UK are relentlessly bombarded with dehumanising campaigns to deprive them of both dignity and rights. It’s why the Lesbians and Gays Support the Migrants (named in honour of the miners solidarity group that inspired the movie ‘Pride’) literally pushed themselves onto the parade route. Or why people in Madrid and Sevilla put the fiesta on hold to push their shame back onto fascist collaborators. The struggle is real, material; against border guards and cages, medical gatekeepers and denial of service. But it’s also about destroying the debilitating shame that serves only to deprive LGBTQ people of a voice, of a place on the street, of a right to live as we truly are, and it’s a fight we can only make collectively. Our public presence on the street together is a refusal of the demand to feel shame, to hide, to live in disgrace.

For my subscribers:

Thanks so much to all my subscribers, free and paid. I really value your support. I send out a free essay or story every month, but for $5 you can get a new one every week. If you want to get them straight to your inbox, you can subscribe here.