What beguiles us in history are often the most transient and ephemeral things, because we see in them something of the intangible of our own lives. What will pass away, what will go barely noticed, what means so much to us now. L.P. Hartley signed himself a place amongst the immortal when he wrote “The past is a foreign country. They do things differently there.” But who doesn’t love to travel; the everyday becomes so strange, and you want to taste everything.

Two friends came over for dinner this week. They’re about to travel, leaving town for a few months. A year maybe, to live in another country, to experience another culture, two Catalan boys together clinging. We had a little food, they bought a bottle of vermut and we drank it, and then they told me had a present. “We thought you’d like it” A. said, handing over a thick book they picked up in a secondhand shop: 100 Gays: Una Lista Ordenada de Los Gays y Las Lesbianas Más Influyentes del Pasada y El Presente. It’s the Spanish edition of a book by Paul Russell, published in English under the title The Gay 100 in 1994.

The pleasure came on opening it up; it had been heavily annotated by a previous owner. For many people this is a curse. They hate to see the pristine printed page defaced. Me, I don’t mind; it’s a tradition as old as time, with mediaeval scribes writing things like “The work is written master, give me a drink. Let the right hand of the scribe be free from the oppressiveness of pain” in their margins, or “A day will come in truth when someone over your page will say, ‘The hand that wrote it is no more.’”

Annotate your books, but please, make it good. Make it like the anonymous owner of 100 Gays, who signed their notes only ‘R.’, but gave us everything else they had. On the spare pages at the front and rear of the book, R. has added their own notes, remarks, poems and theories. On the front page they’ve inscribed it with the place and date:

Barcelona, Otoño 1999.

There’s little more information about the scribbler than that, but the notes they’ve made are a guidebook to that foreign country of the past, a tender reminder of how different things were, and how recently.

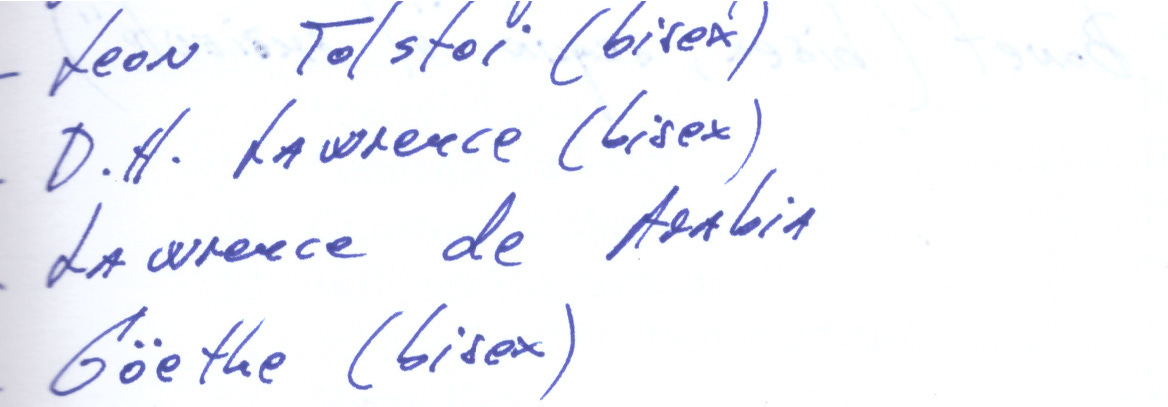

The book lists the gays in order of importance, starting with Socrates, going through Gertrude Stein, Kit Marlowe, Emily Dickinson and Yukio Mishama before ending, somewhat improbably, on US talk radio host Michelangelo Signorile. The bulk of R.’s annotation are an addendum to this list; in a beautiful handwritten addition, R. has named 131 more — some known homosexuals, others news to me — as well as additional observations. Errol Flynn, Julius Caesar and Doris Day are all annotated (bisex) for bisexual,

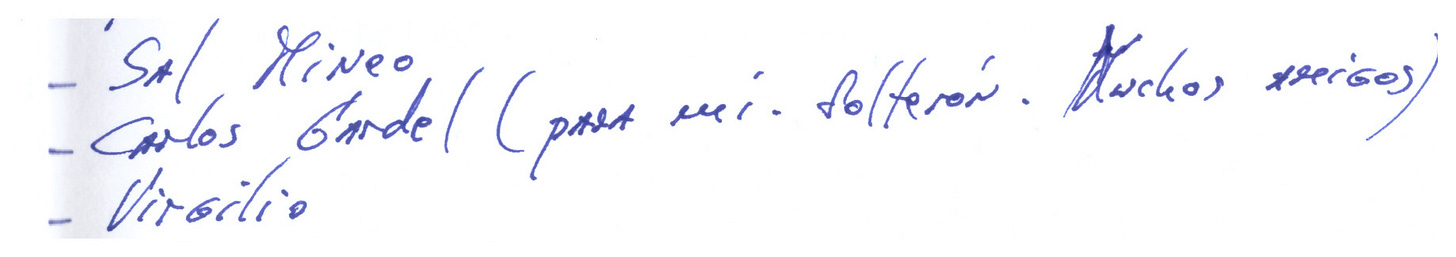

while others, in a touching and enigmatic notation, are simply followed with the note “para mi” [“to me”]. It’s hard to know whether “to me” means R. has made that assumption, thinks they’re gay or bisexual, has heard a rumour, half-remembers reading something, or whether there’s something deeper, a sort of reading of something queer in their essence — para mi, they’re family — or a mixture of both. Many are names famous within Spanish and Latin-American culture, but less well known in anglophone countries. The French-Argentine singer Carlos Gardel, for example, a legendary and handsome performer of tangos who died young, tragically, in a plane crash, is described thus:

– Carlos Gardel (para mi. Solterón. Muchos amigos.) [Carlos Gardel. (To me. Bachelor. Many friends.)]

R.’s notes emerge from such a specific time and space, and capture something important about gay history — its fluid interaction with oral culture, with gossip, which is values, with what is passed on person to person. The list includes a lot of names from Catalan culture, who I won’t include here, because many are still alive and not, as far as I know, openly gay. Here, they are — journalists, authors, television hosts, singers — listen alongside their supposed lovers. Besides one female Catalan politician, the note:

(Bisex...dicen). (a mi me parece que no) [(Bisexual… they say). (I don’t think so)]

One of the most famous Catalans of all is there — I’ve always wondered myself — the architect Antoni Gaudí. About him, R. writes

Gaudi (para mi. Sublimado. Sensua/-espiritual) [Gaudi (for me. Sublimated. Sensual/-spiritual)]

While Gaudi sublimated his sexuality, others weren’t so lucky. Many in R.’s list are described as reprimido, en mi opinión (repressed, in my opinion), usually followed by Misógino ++, including Ernest Hemingway, José Luis de Vilallonga (the Spanish co-star in Breakfast at Tiffany’s), Adolf Hitler and, inevitably, the former Spanish dictator Francisco Franco. Let’s consider reprimido as R.’s shitlist.

Some of the most touching references are towards women, including (repressed) Joan Crawford, whose name is spelled with two love hearts above it. Loca x Bette Davis (Crazy for Bette Davis). My heart aches to read it. Florence Nightingale, listed in the official contents, is annotated with a star. At the bottom of the page, its referent:

Basta una Flor, para salvar a Inglaterra... [One Flower is enough to save England…]

This is more than a list of names. This is a whole worldview; each person appearing on TV, each voice on the radio, assessed for sexual similarity, for tells, for giveaways, for something shared. This is being raised in a hateful and homophobic society, where every rumour of queerness in a filmstar, a writer, a politician, is clung to as a sign of a secret underground of desire. Who keeps lists of names of queer people in their head, their sexuality, their secret loves, their supposed desires ranked? Other queer people, that’s who. Below Crawford is Greta Garbo. She is annotated too:

(“Quiero estar sola”). (La comprendo). [("I want to be alone"). (I understand her).]

I read this to my friends over dinner. “Él era obviamente una reinando!” said G., of R. (He was obviously a queen!) I assumed so too, until the next day, after they left, when, with the help of the internet, I translated the writing from the inside cover of the book. It’s clear to me from this short treatise on their own desire that R. was a lesbian. I reproduce here in full, with apologies for any mistakes in translation:

Para mi, lo mas dificil, es hacer entender a la sociedad tanto homosexual como hetero, que lo que me atrae de las mujeres y concretamente de muy pocas no es el cuerpo, sino El Alma… ya que, y en definitiva, lo que me enamora es el personalidad … femenina. A saber esa mezcla de fuerza y feasibilidad - fuerza fina le llamo - que tan solo y en la grado mas depurado lo que alcanzar, precisamente, una mujer.

Y de tal manera es asi, que la sexualidad GENITALIZADA - propriamente dicha - aunque importante, es realmente secundaria para mi. Extremo es ultimo, dificil de entender incluso para la hembra humana, y, para el varon, practicamente imposible.

Y esa es la clave. Justamente.

[For me, the most difficult thing is to make society understand both homosexual and hetero, that what attracts me to women and specifically very few is not the body, but The Soul ... because, and ultimately, what I love is the personality ... female. To know that mixture of force and ugliness - fine force I call it - that alone and in the purest degree that I reach, precisely, a woman.

And in such a way it is so, that the GENITALIZED sexuality - properly said - although important, is really secondary for me. Extreme is last, difficult to understand even for the human female, and, for the male, practically impossible.

And that is the key. Exactly.]

I think part of what I find so moving in R.’s annotations is the intensity of the expression, as if, finally, a place has been found in which these long considered feelings, nurtured in the breast, can be put down, explained to the other gays in the book of gays. The notations are a testament to a queer life lived, fought for, won. We know so little of R. but we can presume from the references, and having being written in 1999, that in all likelihood R. was born and raised either in Francoist Spain or very shortly after, when LGBTQ people were persecuted and imprisoned, with the full weight of the Catholic Church enforcing strict Catholic morality from the population. This summer I ate at a Galician restaurant which had a dinner show — two cabaret crooners and two drag queens. The average age of the performers, without exaggeration, was probably mid 70s, and behind one of the brilliant queens was a poster from her younger days, dressed in male attire, taken in the 1960s or ‘70s. As the waiters bought over another jug of beer, and she joked about finally getting “her operation” — a hip replacement, of course — I considered what lives these queens had lived, growing up under Franco and the Church, living through La Movida, a social movement that lifted some of the traditional taboos enforced by Francoism, before the AIDS crisis and a huge wave of heroin addiction hit the country. No wonder R. comes back to the Church again and again in her notes, referring repeatedly to the hypocrisy and the libidinal power of sexual repression:

La Iglesia Catolica, es una Theocracia de varones celibes. No es necesario tener un cerebro atomico, para darse cuenta de que, el Vaticano, es un nido de homosexuales…. Eso si, alto status y mayoritariamente castos....

Evidentemente, de aki, no puede salir nada bueno para la mujer

[The Catholic Church is a theocracy of celibate males. It is not necessary to have an atomic brain, to realize that the Vatican is a nest of homosexuals.... If that, high status and mostly chaste.....

Evidently, from here, nothing good can come out of it for the woman.]

Following R.’s list, the book is otherwise unannotated, but after the index, the final page returns to her theme; a poem, I assume of her own composition, which pulls together her marginalia. It is both a sexual fantasy and a political manifesto, a utopian hope pulled from the existing society in which she lives, the repression finally lifted. I read it and wondered where she is, right now. Perhaps she is no longer alive, and this book found its way, neglected, from a post-mortem house clearance of unfeeling relatives. Maybe, with luck, she has found a place, happily, where she can retire in lesbian bliss, and no longer needs her catalogue of famous pink comrades. Either way, I’m so grateful A. and G. picked it up for me, so glad buena fortuna found it into my hands, and I can appreciate this moment of recent history, share her tender notes with you, and remember that as LGBTQ people, we stand upon the shoulders of giants. Her poem:

El Sueno Rosado

Una orden de Monjas Lesbianas

“Las karatecas de Jesu”

Tambien conocidas como

“Las Teclas”

Order severa, de cultura extraordinaria.

Universitarias todas, muchas de ellas, becadas por su teroreria

Plusinacional. Plusiracial.

Autoritaria, pero democratica,

Gran elevacion espiritual

Uniforme sobrio. Pantalones a voluntad.

El Capellan seria “gay” … Naturalmente…

The Pink Dream

An order of Lesbian Nuns

"The karatecas of Jesus"

Also known as

"The Keys"

Order severe, of extraordinary culture.

University students, all of them, many of them with scholarships for their theory.

Multinational. Multiracial.

Authoritarian, but democratic,

Great spiritual elevation

Sober uniform. Trousers voluntary.

The chaplain would be "gay" ... Naturally...

utopian drivel is a weekly essay or audio essay subscription service from Huw Lemmey. Apologies for any translation errors in this week’s essay, and thank you to all my subscribers for helping keep the show on the road. Please feel free to share this post/email with anyone who might be interested. If you’d like to know more about utopian drivel, click here. And you can subscribe below.

Beautiful.

Thank you for sharing it.