The Anatomy of a Joke

On Fisting Norman Lamont

Nothing is as unfunny as a joke analysed. Still, I’m going to do it anyway. That’s because, some 31 years after it was told, there’s one joke I find myself returning to again and again, finding new resonances, new power, new humour in it. The more I hear it, the deeper it gets, so to speak. It was a joke so powerful that it derailed the joke-teller’s career, at least for a while. Yet it lingers as a legend, and for good reason.

The joke landed like a stone dropped into a stagnant nation. It was 1993, and Britain was in the doldrums, politically, culturally and socially speaking. The destructive dynamism of Thatcherism had exhausted itself, and the country was left with a Tory party in power that was rapidly ossifying. Thatcher had been toppled in a palace coup in late 1990 over the party’s internal divisions over Europe (plus ça change,) and she was replaced by the uninspiring figure of John Major, who saw out the remainder of her parliament under a spectre of high interest rates, high inflation, and high unemployment. Despite winning a surprise victory in the 1992 General Election, his party never seemed to recapture the popular momentum of the Thatcher era, and pop culture followed suit, perhaps sensing little to push against. The pop charts were dominated by the boyband Take That and M People, while top TV ratings were won by shows like the lighthearted ‘60s cop drama Heartbeat or the home video clip show You’ve Been Framed! It was only really in contemporary art and in comedy that there were stirrings of something interesting happening; the YBAs were beginning to break through into popular consciousness, while 1993 saw the debut of The Mrs Merton Show and The Smell of Reeves and Mortimer.

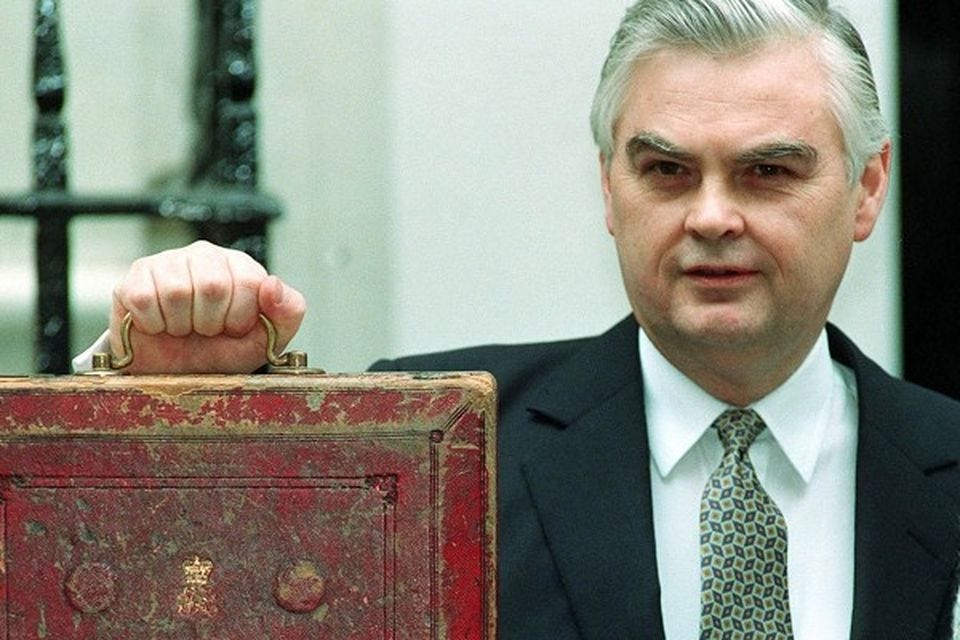

Out of ideas, the government nonetheless trundled on, struggling through economic crises of its own making. After Britain dropped out of the European Exchange Rate Mechanism, Norman Lamont, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, resigned, delivering a bruising blow to the government when he quipped in his resignation speech that the Tory Government "gives the impression of being in office but not in power." It was a punchy little line that resonated precisely because it seemed to distil exactly the sentiment of the country. But the real joke was to come later, at Lamont’s expense.

6 months after Lamont’s resignation, he was presenting an award, for some reason, at the prestigious ceremony for the British Comedy Awards, a black tie dinner affair broadcast live on TV to honour the year’s comedy successes. The list of winners is an impressive overview of the great and good of comedy broadcasting at the time: French and Saunders, Steve Coogan, Richard Curtis, and Rik Mayall had all taken to the stage to collect awards that night, a stage decorated, inexplicably, to look like an abandoned gothic horror graveyard, complete with cemetery gates and creeping ivy. The host, Jonathan Ross, had been compering the event from behind a lectern designed to look like an old tomb. To present the award for Top Television Personality, he welcomed to the stage the stand-up comedian Julian Clary, who had made his name as an outrageous camp stage performer and virtuosic euphemiser, before breaking into TV with his own show, Sticky Moments. He was one of only a handful of openly gay comics on TV at the time, a new brood following on from a nation’s tradition of keeping their gay comedians simultaneously close to their hearts and locked in the closet. Best here to watch the clip, before I precis it for those who can’t watch.

“Very nice of you to recreate Hampstead Heath for me here,” Clary quips, a reference to North London’s notorious gay cruising ground. “As a matter of fact, I’ve just been fisting Norman Lamont.” The audience erupts into something more than laughter: you can see Armando Iannucci breaking up. Mark Lamarr is howling; Martin Clunes is crying. Onstage, Clary struggles to even get the punchline out: “talk about a red box!” (an allusion to the red despatch box which the Chancellor traditionally brandishes to the press to announce a new budget.)

The joke is a good joke, an outrageous pun and visual image against an authority figure wrapped up in a classic format. But there’s an extra power to it, a power that finds its source in how gay men were understood by the wider public at the time, and how the Tory party, of which Lamont was a member, treated them. It wasn’t a good time to be gay. Social attitudes about homosexuality had actually grown increasingly negative through much of the 1980s, as the AIDS crisis hit the UK, and as gay people became more visible in mainstream society and the media. By 1993, some 65% of Britons regarded homosexual relationships as often or mostly wrong, with only 18% regarding them as “not wrong at all”. What’s more, the HIV/AIDS epidemic was hitting the community hardest at this time, with highly active antiretroviral therapy still a number of years away. 1993/94 marked a peak for AIDS diagnoses in the UK, and 1994/95 for AIDS deaths.

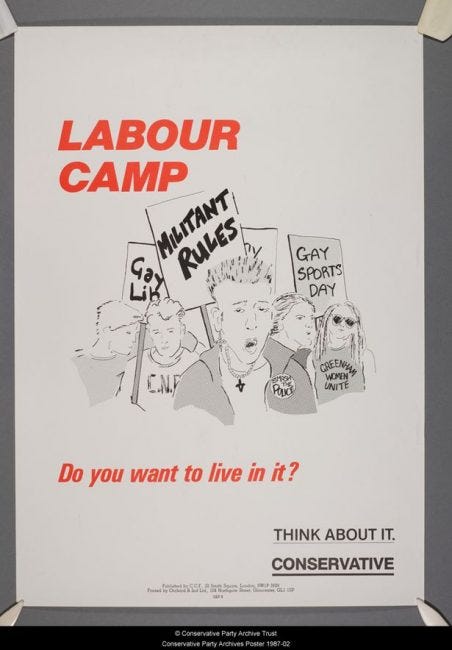

1987 Tory campaign poster. And the answer is “yes.”

The fear of AIDS in a population scared half to death by government messaging on the epidemic — the major 1987 public health awareness campaign on the disease featured a enormous monolith engraved with “AIDS”crashing to the ground, with the tagline “Don’t die of ignorance” — fuelled a moral panic that the government in turn took advantage of. LGBT rights was seen as part of a “loony left” agenda, and anti-leftist homophobia in the media and government reached a fever pitch, as I discussed in this piece a few years ago, with suggestions that left wing activists, out-of-touch teachers and academics, and sex perverts were not just “shoving it down our throats”, as the old chestnut goes, but conspiring to corrupt our children and silence their legitimate concerns. It all sounds achingly familiar to anyone with half an eye on the most recent British culture wars of the past decade or so. This moral panic resulted in the passing of Section 28, an anti-gay education law that stayed on the books until the early 2000s. The moral panic around sexual deviance, and the implication that gays were after your kids, not only fuelled the idea that gays were abject and disgusting, and the engineers of their own suffering, but also helped prevent exactly the sort of sex education that could have mitigated the epidemic.

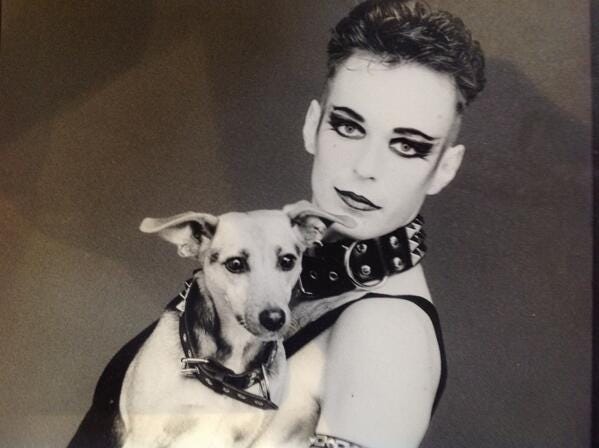

Clary was a tonic in this atmosphere. He acted as an alchemist on queer abjection, turning what was regarded as dark and degrading into camp entertainment, and bolstering defiance against this moralism not by disguising his joy in sex, but revelling in it. Walking out to thunderous applause, he would thank his audience, saying “I do enjoy a warm hand on my entrance,” and his gameshow Sticky Moments would bring this very pretty boy with a filthy mouth and a pair of hotpants into the nation’s living rooms. He is, in a word, charming, but in an atmosphere as hostile as the early ‘90s was for gays, that charm was transformative, even magical.

Clary with Fanny the Wonder Dog in 1989

What is perhaps more astonishing is that, while his star was ascending across the TV skies, he was facing the very sharp end of this gay crisis. In his 2005 autobiography A Young Man’s Passage he provides a non-exhaustive list of guys he’d fucked, including “the boy from Hove youth hostel,” “Sensible Ian,” “Pop-it-in Pat,” “Palma man with one eye,” “Henry with the dirty sheets” and the “former RUC man with real bullet scars and colostomy bag.” Nestled in among the conquests is a love, “Christopher the Dead Boyfriend,” whom Julian had met and fallen for before he disappeared off the scene a while. When he returned into Julian’s life, he told him that he had AIDS, and that he loved him. There is a chapter on Christopher’s illness and death, a deeply moving passage that will be immediately familiar to anyone who has sat with someone through the end stages of a disease that will slowly kill them. He captures the fact that we walk through this unfolding catastrophe in an almost pedestrian fashion; moments of trauma, like the realisation Christopher is near his end whilst on holiday, and having to smuggle him home on a flight, are balanced with the fact that the world around you doesn’t recognise the solemnity and horror of what is happening, and buses still run and TV shows still written and the hospital rooms of the dead are still soon filled with new dying.

Christopher died in 1991, with Julian having cared for him throughout his illness. In the aftermath he understandably struggled, and has talked on occasion about the sense of depression he felt without his lover by his side, and his cocktail of drugs — valium during the day, and rohypnol at night — to try to control the frequent panic attacks he suffered. He had popped a valium as he took to the stage that night, having spotted Norman Lamont in the audience, and feeling pretty sick of the whole damn charade.

“Fancy inviting him, I thought,” he would write later, “How inappropriate.” Still, the man is nothing if not a consummate entertainer, and the show must go, loss and the black dog notwithstanding. Appearing on RTÉ’s The Late Late Show a few years ago, he mused on how it was “a very contradictory thing, being funny for a living, then having all that grief to deal with.” But Lamont’s appearance was inappropriate: prior to being the Chancellor, Lamont had been a junior minister throughout Thatcher’s administration. What’s more, Major had tried to reinvigorate his flagging political remit and win back his backbench support by restoking the culture wars against the social liberalisation of British society. Appearing at the Tory Party conference in October of 1993, he had announced a new campaign, saying “the message from this conference is clear and simple: we must go back to basics.” Back to Basics meant not just a return to classic Conservative principles of free trade, but to social and moral values as well: “traditional teaching, respect for the family and respect for the law.” It included a thinly veiled attacked on young single mothers, a tabloid moral panic all of its own at the time.

John Major with fellow Tory MP Edwina Currie, with whom he cheated on his wife.

The speech was Major’s attempt to rebuild a political base by appealing to the same “common sense” Conservatism, and the same culture war rhetoric, as Thatcher. His Back to Basics speech bears a familial resemblance to Thatcher’s 1987 conference speech, where, a bolder and more charismatic politician than Major, she drove home her point more explicitly, declaiming that “children who need to be taught to respect traditional moral values are being taught that they have an inalienable right to be gay. And children who need encouragement—and children do so much need encouragement—so many children—they are being taught that our society offers them no future. All of those children are being cheated of a sound start in life—yes cheated.”

Major was playing the old hits to the party faithful. That’s what made Clary’s joke both so shocking, and so profound: it went to the heart of the political fiction which the Tories were trying to spin, at the expense of gay people, by bringing them down to our level.

For years Tories had been painting gays as depraved, and homosexuality as dirty; the language of homophobia in the 1980s and ‘90s was so visceral. Filth, shame, and cesspits of their own making: buggery, sodomy and fornication; disease, sickness and endless references to committing acts, as though each incident was a crime. Suddenly, Clary was turning the tables; he was reducing the Tories to purely physical and the sexual beings, just as they had done to gays. In a time when hardcore pornography was much less readily available, the invocation of the act of fisting was much more mysterious. Its connotations were both gross and hilarious (not my personal opinion, of course,) and the image of a red box vivid, even violent, and yet the butt of it, so to speak, was not us, but a Tory grandee.

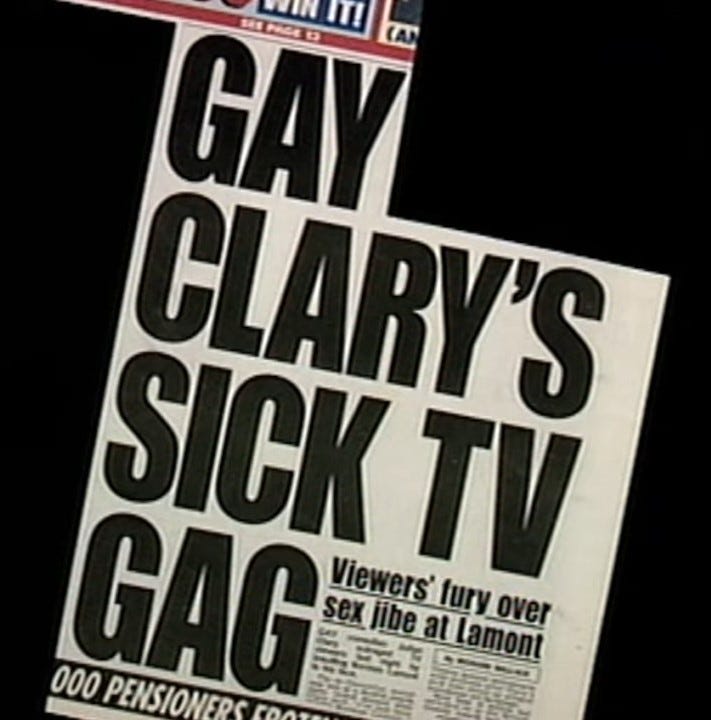

The joke flipped power on its head somewhat. He could have been getting a blowjob from Norman Lamont, or jerking him off, or fucking him. But by choosing a sex act like fisting, he somehow brought it onto gay territory, into a gay argot. The next day Britain’s tabloid press, hand-on-glove comrades with the Tories in any culture war, were appalled, despite the fact the live broadcast only received 7 complaints, out of 13 million viewers. The Sun headline read “GAY CLARY’S SICK TV GAG”. Speaking over a decade later with Boy George, he said “The headlines the next day - they kept calling it a “gay sex act”... I think fisting is available to anyone, isn’t it?” Well, yes, but also no. It was, at its heart, a gay joke, and not just because it was between two men, but because it tapped into gay knowledge. Suddenly sexualisation was a two way street, and they were getting a taste of their own medicine.

The years that followed were hard on Clary, by his own admission, as he continued to struggle with panic attacks. It’s sometimes claimed he was banned from TV following the joke. He wasn’t, although it was years before he was trusted again to appear on live TV. But his career faltered, and he took time to process his grief and his anxiety. There’s a pretty astonishing appearance on Ruby Wax’s talk show in 1998 where, appearing alongside Wax, Ivana Trump and Dana International (iconic), he suffers a panic attack live on air. It’s a difficult watch for many reasons — not just Wax’s graphic obsession with Dana International’s transition, but also to see him struggling.

Things didn’t go much better for the Conservatives. Their Back to Basics campaign for common sense and decency backfired when it turned out that the Tory Party consisted largely of Tory MPs, and they were caught over and again with their pants down, politically and literally, doing what Tory MPs do. Fraud, corruption, and sex scandals galore, including a number of secret gay affairs and pregnancies with secretaries, led to Back to Basics becoming a joke itself, and one that just drew more attention to the moral hypocrisy of conservatives. Perhaps there was a sense in the audience that night that Clary was just saying what we all knew: the Conservatives are all nasty little perverts too.

The degradation of traditional family values ended up happening not at the hands of gays or single mothers, but at those who claimed them as their own, and wanted to use their political power to force them on others. In that context, the frankness of public voices like Julian Clary seemed less obscene than prescient and refreshingly honest. Norman Lamont would lose his seat at the next election when the people spoke, but soon found himself back in politics, ennobled as a Lord in Britain’s second chamber, a neat little trick the British establishment has for speaking back to the people and correcting their mistakes.

Once Clary bounced back, not into the Lords but primetime TV, he found himself riding the wave of changing social attitudes to gay people, as well as personal affection for himself. He rejects the term national treasure, preferring “national trinket”, but I think the way he handled his career downturn and public hounding for his joke probably contributed to the sense of general public warmth that now gilds his profile. He was an underdog who showed his spunk. Today moral panics are back on the horizon. In a recent profile for the Guardian, Clary was prodded to take part in the culture war, asked about whether safe spaces and cancel culture were killing comedy. “I quite understand things like safe spaces and refusing to engage,” he replied “because life’s too short. I get that.” Given his experience with loss, that “life’s too short” packs a punch, so to speak. How much of our lives are we to give our enemies?

Trinket or not, Clary, like his friend, the late lamented Paul O’Grady, will always have pugnacious, gay edge to his humour, because he understands the stakes. When asked whether, by being the man he is, he is contributing to his own persecution at the hands of homophobes, he stated “No, because I don’t ever think of myself as a stereotype. I have the right to be a camp, effeminate homosexual.” That stalwart refusal to dim yourself for others still has far more power to shock and offend than any fisting joke.

Can’t get enough of me? Well who can blame you. This week I had a piece on my mum, grief, and cooking, up on Vittles, which you can read here. I have also written an essay, “Mass Market Masters,” to accompany the new catalogue for the Tom of Finland/Beryl Cook hit exhibition at Studio Voltaire this summer. The catalogue, like the show, is superb; you can buy it here.

If you’d like to read more of my work, please do subscribe to this newsletter. It’s been going for five years, so there are hundreds of essays to read. Paid subscribers get access to the whole archive. Why not start with one of the most popular ones, this essay about watching the funeral of Queen Elizabeth II live from a gay sauna under Waterloo Station?

Really great piece. Shared it a bunch, might even mention it in a class on Wednesday.

I loved getting the joke explained! Thank you!