Last week I looked at the coverage of gay people in the first twenty years of Private Eye magazine. This week I look at the following forty or so years in part II of “Poove Power”. If you haven’t read part I yet, you can find it here. Also, before I start, I’d like to add a little content note that this piece contains some substantially “stronger stuff” than the last in terms of aggressive homophobia and transphobia.

By the end of the 1970s queer culture was in a much stronger position, socially, politically and legally, than it had been a decade before. While the period after partial decriminalisation in 1967 had seen an upsurge in legal persecution of gay men, and there was still an enormous social stigma attached to homosexuality, gays had nevertheless began to build a much larger, more open culture of nightlife, publishing and other cultural outlets, particularly in larger cities. They had also managed to politically organise much more widely, especially on the left, around gay issues. As a result, the perception of gays was changing. As I mentioned last week, the impression of tragic, older, lonely and predatory old pooves was disappearing in favour of younger, tougher, more perverted leather and denim gays. We could discuss an alternative history here, of what might have happened if that social process had continued largely unhindered, but such counterfactuals are both foolish and, in this instance, tragic, as in the first few years on the decade a new crisis emerged within the UK gay scene, one which would change wider public perceptions of gay men in particular: HIV/AIDS. But before we reach that juncture, it’s worth looking at some of the Eye’s takes on gay activism, which Ingrams regarded as a taking advantage of the magnanimity of heterosexuals decision to decriminalise.

A popular theme in the press in the 1980s was the rise of the so-called “loony left”, and particularly the actions of the GLC, who were beginning to provide some money and resources within local councils for minority groups. In retrospect, many of the policies that were seized upon by the right-wing press seem so minor or worthwhile that the intensity of the reaction seems farcical. For example, Brent Council appointed an advisor to liaise on race relations in local schools; the backlash was often intense, and pushed not just by a hostile right-wing press but also by the right of the Labour Party, seeking to clamp down on socialist policies. On the issue in Brent, Roy Hattersley, a prominent figure on the party’s right, declared the policy amounted to “unacceptable behaviour” and said “I want to eliminate it." Another controversy was around a large grant given to establish the London Lesbian and Gay Centre in Farringdon, a large, non-commercial community space for queer people.

Some satire. Private Eye, January 1982.

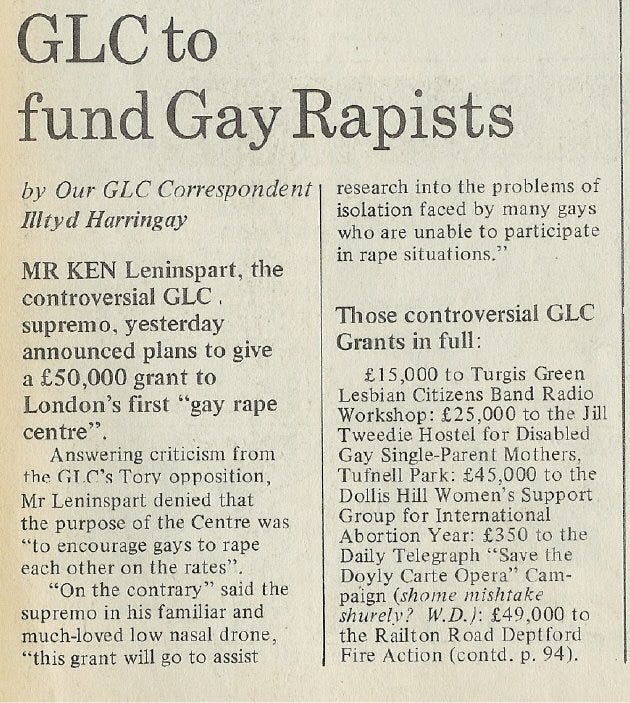

Support for gay and lesbian groups, especially from the left-controlled GLC, became a key battleground in the right-wing attack on the “Loony Left”, combining both general homophobia with increasing fear and ignorance over the deepening AIDS crisis. Private Eye rode the wave of mockery against the Loony Left, Ken Livingstone (the leader of the GLC at the time), and particularly against gay and lesbian people.

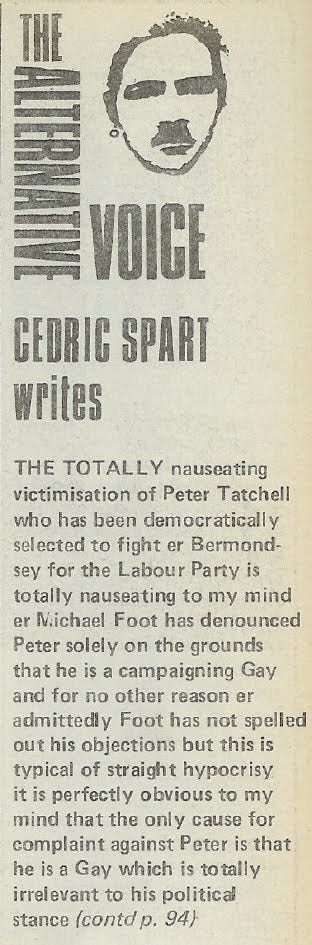

A regular column in Private Eye for decades is purportedly written by “Dave Spart”, a parody of far left activists in the UK. In 1983, the Eye ran a special version of the column under the name “Cedric Spart”, using the same photograph as Dave, but with a moustache and earring. Cedric was present to comment on the ongoing furore around the Bermondsey by-election, which was being contested by left-wing Labour candidate and prominent gay rights activist Peter Tatchell.

Tatchell had been selected by his constituency party, but his strident leftist views had been opposed by many in the party bureaucracy, seemingly under the mistaken belief that Tatchell was a member of the Trotskyist Militant tendency (unlikely, given Militant’s opposition to homosexuality). Labour leader Michael Foot (uncle of Eye journalist Paul Foot) and the party’s National Executive Committee refused to endorse him, and reran the selection process, which Tatchell again won. The resulting by-election campaign, run under intense scrutiny by the national press, was a run-off between Tatchell and the Liberal candidate Simon Hughes. The campaign was both deeply homophobic and at times violent; Tatchell was attacked in the street and his home was vandalised, and received death threats, while the Liberal party had male canvassers wearing badges saying “I’ve been kissed by Peter Tatchell” and released a pamphlet declaring it was "a straight choice" in Bermondsey. Private Eye profiled the affair on its cover.

Private Eye cover, February 1983. “The Tendency” refers to both Militant and being “that way”.

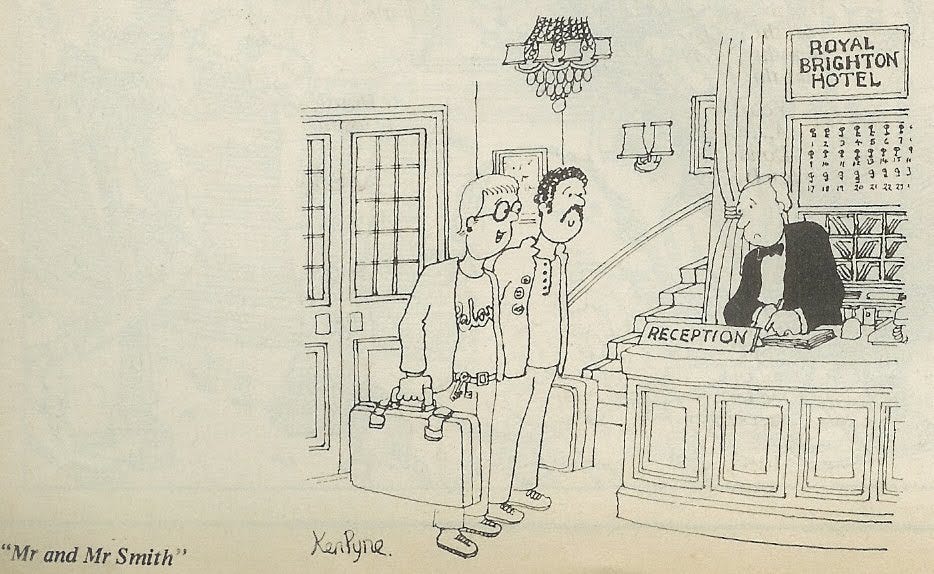

The effects of the prolonged press campaign against the “loony left” were not restricted to abolition of the GLC by Thatcher via the Local Government Act 1985. It also was a significant contribution to the moral panic around the role of gay and lesbian people in education, and the teaching of young people about gay and lesbians. In 1983 the Daily Mail ran a hit piece claiming the childrens’ book Jenny Lives with Eric and Martin was being put into school libraries in London. Despite the book being an entirely innocent book about a gay couple and their daughter, it wasn’t even true: the book was in an internal library of materials for teachers. Nonetheless it helped to kickstart a campaign that resulted in Section 28, a prohibition on locals authorities promoting homosexuality in schools, or promoting “the teaching in any maintained school of the acceptability of homosexuality as a pretended family relationship". The section became law in 1988, leading to a widespread suppression of not just the specifics of the law, but on counselling and helping young gay people in general, either out of fear of prosecution, or using the law as an excuse to fail to provide care by homophobic teachers. The law stayed on the books until it was repealed in 2003. My entire education was covered by this period, and when I came out in secondary school, I felt its presence keenly. Private Eye found the notion of the “pretended family relationship” fertile ground for humour.

Cartoon by Ken Pyne, August 1984.

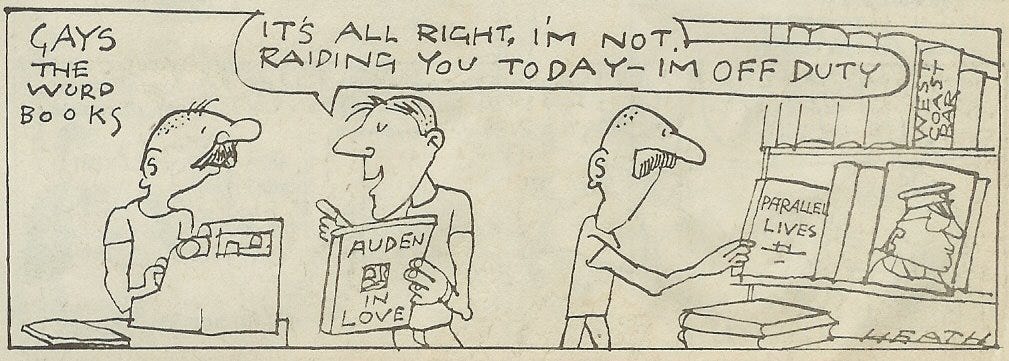

Private Eye also made much of the ongoing suppression of gay literature by the Thatcher government, and by the increased policing gay men in particular were experiencing. The rising homophobia that accompanied the AIDS crisis provided ample political capital for a conservative government keen to preach, if not practice, a return to traditional values. Emboldened police forces cracked down not just on cruising spots, but also on gay bars and gay bookshops. Gay’s the Word bookshop imported much of their literature from the US; in 1985 Customs and Excise raided the shop, seizing thousands of pounds worth of books, including the plays of Tennessee Williams and Jean Genet, citing them as obscene materials.

Michael Heath’s ‘The Gays’ strip for Private Eye, April 1983

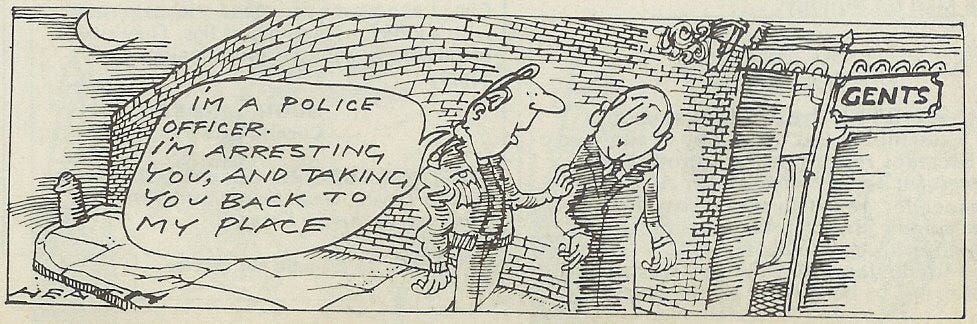

The ongoing cartoon strip by Michael Heath, The Gays, made much of this crackdown, especially focusing on the use of so called “pretty policemen”, attractive younger PCs used to honeytrap men into sexual offences. The subject of the satire is two-fold: the hypocrisy of a police force that, he assumed, contained gay men then cracking down on other gay men, and gay men who somehow desired the suppression of police. The idea that homophobia is a gay-on-gay crime, that homophobes are troubled gay men unable to come to terms with their sexuality, is a lingering one, displacing responsibility for homophobia from a straight society onto gay men themselves. It was also a favourite trope of Heath’s (who, I admit, I nonetheless think is one of Britain’s great cartoonists) in “The Gays”.

“The Gays”, March 1984

Although coverage of gays under Ingram’s editorship had always been pretty unpleasant, there is a definite sense that while he started off as a more liberal if mocking voice had changed. By the 1980s, with the GLC and increasing calls for gay rights and representation becoming an irritant for him, his tone had become more aggressively homophobic, something noted even at the time as having parallels with the Eye’s history of antisemitism. Writing in 1982, Julian Barnes remarked, I think accurately, that “To the charge of anti-semitism, Ingrams replies that the Eye is anti every other minority too, and that Jews have ‘become much too sensitive; they should be more tolerant of criticism, as they used to be.’... like homosexuals, they have got a bit uppity, and need to be reminded of this very English truth: that by toleration we do not mean equality.”

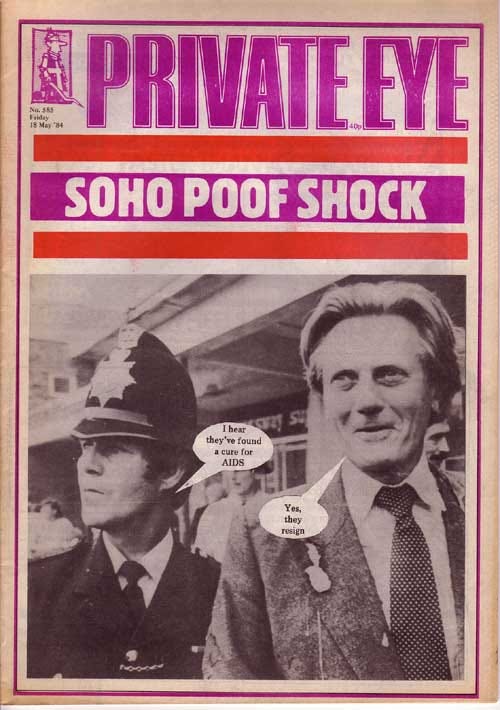

Private Eye cover, May 1984, after one of Defence Minister Michael Heseltine’s aide Keith Hampson MP came on to a man in a Soho gay club who, it turned out, was an undercover police officer. Although the charge was dropped, Hampson was forced to resign. Aide/AIDS is the joke you’re looking for here.

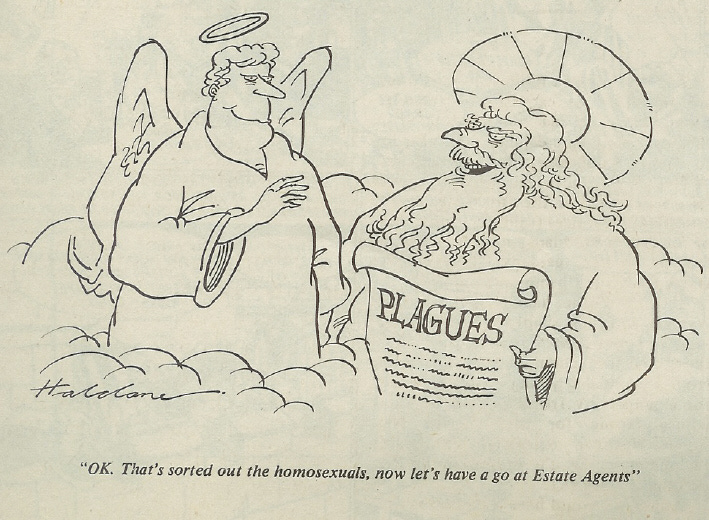

Haldane for Private Eye, August 1985

Homosexuals, having grown too big for their boots, were by the mid ‘80s a stock target for Private Eye, a magazine that is forced to recycle much of its material, and to establish tropes, due to its regular fortnightly publication schedule. It feels like, when the AIDS crisis began to emerge in the UK, the Eye responded with the sort of casual cruelty it had become use to, unable to see the enormous human tragedy unfolding in the country. Much of its coverage of the AIDS crisis, from the first acknowledged death in the UK in late 1981 right up until the nineties, was marked by an almost gleeful cruelty that, in all honesty, would not have been out of place in a National Front newspaper. In 1983 Auberon Waugh wrote in his diary piece “Would the Gay Community take it very badly if I suggested that American homosexuals visiting Britain should be required to spend six months in kennels before being allowed out to take their pleasure with the natives [?]” As ‘UKJarry’ writes on StreetLaughter, Waugh’s piece was “intended here in a sententiously high-toned and blithely semi-nonsensical opinion-proffering manner”, but the irony must surely have struggled to fight through a general culture of fear and hatred around people living with HIV and AIDS at the time, not least when accompanied with the following cartoon.

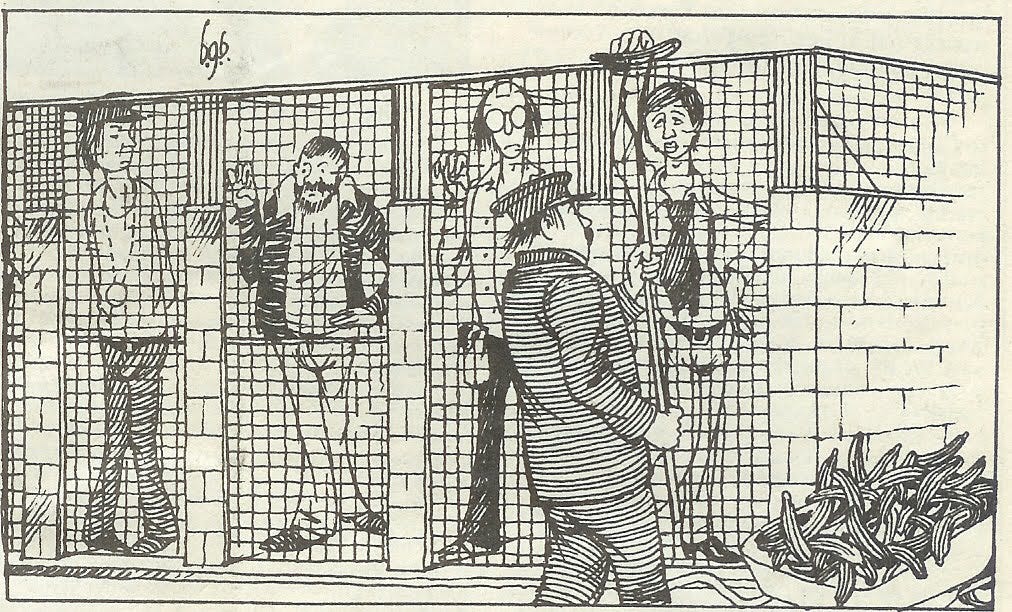

Indeed, just a few years later discussions of concentration camps, forcible tattoos and gas chambers were, if not mainstream, certainly common in a discourse around HIV and AIDS, with dark echoes of persecution of LGBTQ people under the Nazi regime. In the Pink, a gay and lesbian community magazine based in the West Midlands, reported in 1987 on a meeting of South Staffordshire Council where the Conservative Council Leader Bill Brownhill said

I should shoot them all... those bunch of queers that legalise filth in homosexuality have a lot to answer for and I hope they are proud of what they have done. It is disgusting and diabolical. As a cure I would put 90% of queers in the ruddy gas chambers. Are we going to keep letting these queers trade their filth up and down the country?

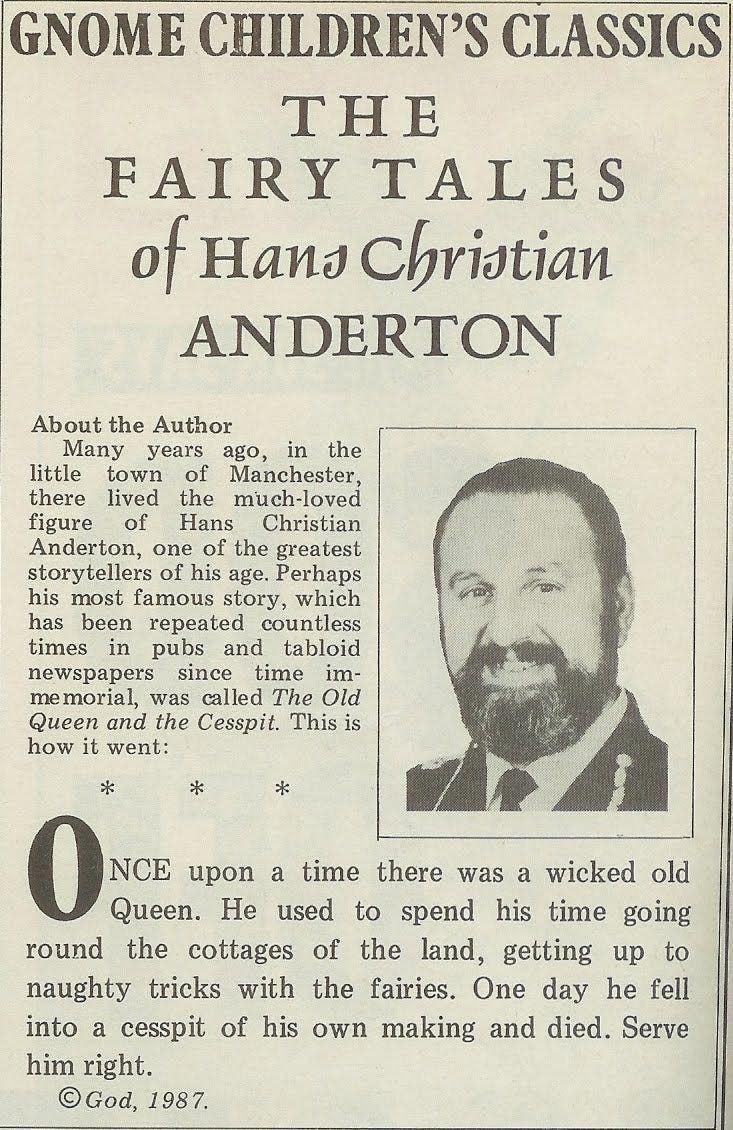

His Labour opposite responded that “Everyone of us here will agree with what has been said,” although the Liberal leader said that "there is little point in queerbashing other than making ourselves feel better." Shortly before, the Chief Constable of Greater Manchester, James Anderton, had said that gays were “swirling around in a cesspit of their own making” and told Women’s Own magazine later that year that "The law of the land allows consenting adult homosexuals to engage in sexual practises which I think should be criminal offences. Sodomy between males is an abhorrent offence, condemned by the word of God, and ought to be against the criminal law." He was knighted in 1990.

Parody piece on Anderton in Private Eye, 1987.

Richard Ingrams was to leave his editor role at Private Eye in 1986. He anointed Ian Hislop as his successor, with Peter Cook’s blessing, when Hislop was just 26, much to the annoyance of the paper’s older generation of writers. There is no doubt that Hislop did make some changes to the paper’s coverage of homosexuality, partly as a result of shifting its emphasis away from mere society gossip. Indeed, as part of the changes he sacked the gossip columnist Nigel Dempster, who had once outed the Labour MP Maureen Colquhoun, making her the first openly gay member of parliament, as well as scrapping the Michael Heath cartoon The Gays.

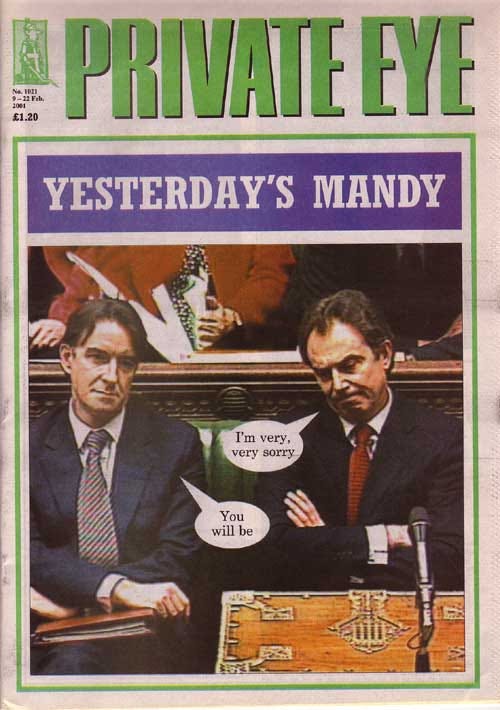

Yet it would be too far to say that Hislop removed the schoolboy homophobia from Private Eye; it lingers below the surface, in its characterisation of Peter Mandelson as ‘Mandy’, the ‘Prince of Darkness’, or in its cartoon “Supermodels” about the fashion world, to take but a few examples. Some of the cruder material that marked the early stages of the AIDS crisis would now be unthinkable in the Eye, but it’s notable that there seems to be very little material at all that is satire from the perspective of gays, for example. Strange, when you think about it; gay satires on heterosexuals are hardly rare, yet the idea of opening the Eye and seeing it there seems almost unthinkable, which somewhat punctures the argument that Private Eye is an equal opportunities offender, with knives out for everyone. There have been gay contributors to Private Eye —Tom Driberg, for example, set the famously filthy crossword — but that’s not quite the same thing.

In the year 2000, the height of Blairism, the BBC ran a feature on the magazine where one respondent said that Private Eye had a policy of refusing to publish classified adverts in the back of the paper for gay and lesbian people. I’ve not been able to find another source for it, although around the same time they also turned down an advert for Interflora on the grounds it was too racy. Of all the aspects of Private Eye’s relationship with gay people, this was perhaps the most unexpected for me. As unpleasant as all the other aspects might be, I can understand their logic within the framework of a libertarian, say-the-unsayable and offending everyone attitude of a satirical magazine, whether or not I agree with the arguments, and whether or not I find the jokes funny. But this little nugget seems uncharacteristically prudish and conservative. Perhaps behind the man-of-the-world attitude a little phobia did lurk; I don’t mind joking about buggery, but I draw the line at facilitating it.

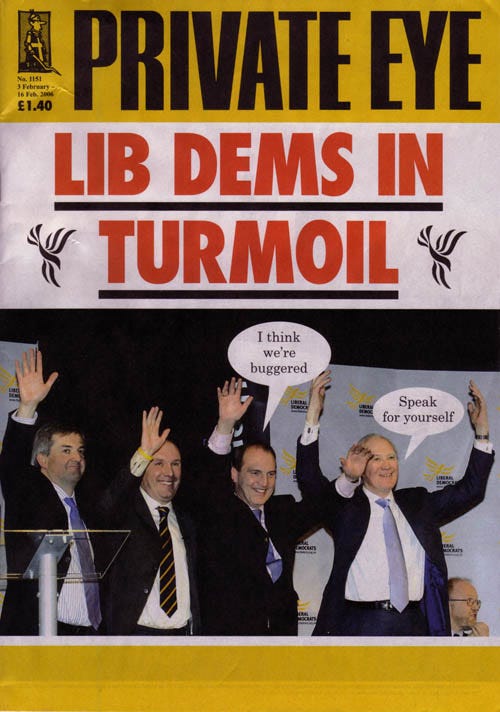

By the mid noughties, public attitudes to homosexuality were changing, although the mere existence of homosexuality was still a workable punchline. Take this 2006 cover playing on the troubles of the Liberal Democrats following the resignation of their leader, Charles Kennedy, due to his alcoholism. The four men pictured were all initially in the running to replace him. In the previous few weeks, however, Lib Dem MP Mark Oaten (second from left) had been the subject of an exposé over having had a threesome with rent boys, while Simon Hughes (second from right) was forcibly outed as bisexual by The Sun after they presented him with “evidence” that he’d used gay sex chat lines. Hughes must have felt a painful twist of irony, given he’d come to power in the Bermondsey by-election thanks to the very same vein of political queer bashing that now denied him his chance at party leadership.

So yes, the Lib Dems were buggered, and if I’m honest, I think you’d have to be a little oversensitive to take too much offence at this pun, although within the wider context of Eye’s history it’s obviously of a piece. What’s more important to point out, however, is that it’s not funny.

Kerber’s “Supermodels” strip, November 2018. Curious as to whether a single human has ever laughed at this cartoon.

I hope we are past the point of no return in terms of normalising gay people in the UK. Unsurprisingly, given the generation and milieu from which the Eye revolves around, while much of the organ’s historic public schoolboy homophobia has taken a quiet backseat, it has been replaced with a more virulent transphobia, one which is echoed within the pages of broadsheet newspaper like the Observer and the Guardian (other examples of liberal British culture mistaken for left-wing) as well as the right-wing outlets such as the Spectator or Daily Mail. While some of that takes the form of the same casual, abjectifying bigotry that gay and lesbian people faced in the past, much of it is “journalism” that takes place under the rubric of the supposed “gender debate”, such as their review of Abigail Shrier’s book on the “transgender craze seducing our daughters”, Irreversible Damage. While there’s an element of truth to the idea that the current attack on trans people is a rerun of past attacks on gay people, it’s not entirely accurate. For a start, much of the homophobia against gay people in the twentieth century was itself also transphobic and hostile to gender nonconformity, even if it couldn’t elucidate the difference itself. Transphobia can also emerge from within the gay community, often from people who were themselves the subjects of homophobic ridicule in the past.

‘Marc’ for Private Eye, November 1982 - one of the few examples of jokes specifically at the expense of lesbians

While the Eye might have prided itself on its worldly approach to homosexuality — it was always funny or pathetic, but never shocking — in its approach to trans rights and healthcare it has adopted a “think-of-the-children” mode of concerned horror not dissimilar to the proverbial Disgusted of Tunbridge Wells they used to mock. Others have done a better job of examining the moral panic claims made in the linked review of Shrier’s book. I will just add that I think on this issue Eye illuminates the very distinct British media culture that has allowed trans people to become such a punchbag from left, right and centre, and where a liberal-left milieu have been the driving force of “respectable” transphobia. The British media is extremely closed in terms of where it draws its cohort from, and very insular in the ways it socialises. Private Eye will no doubt continue to publish some of the more virulent and vicious attacks on trans people because its tradition of anonymous columns allows columnists at other papers to defend their friends and perpetuate the narrative of columnist victimhood and censorship that has become an article of faith amongst that particular generation and milieu of older journalists. I think it’s impossible to get a grasp on the persistence of transphobia within the UK media without understanding the internal dynamics of media culture, as ongoing battles at The Guardian make clear.

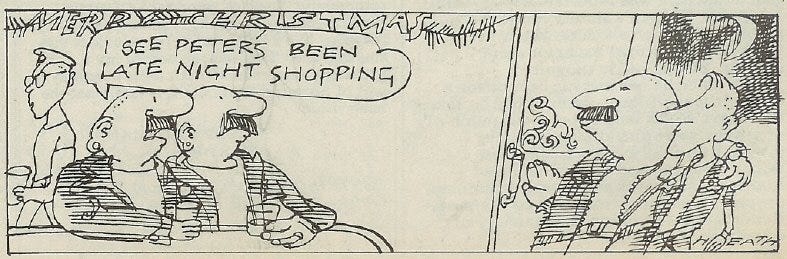

Heath’s ‘The Gays’, December 1984

I wrote this brief queer history of the Eye because I found the cartoons, many of which are archived on the absolutely essential blog StreetLaughter: A Gay Cavalcade of Comic Stereotypesby the blogger ukjarry, to be fascinating primary sources for attitudes towards gays at the time, illuminating a less official public mood about what gays meant, and how they were seen. I wanted to put together that history partly because the magazine emerged during the 1960s process of liberalisation, and in tracing that history through one publication we can see what liberalisation might actually mean in practice, negotiating a tug-of-war between legal behaviour, public disgust, creeping toleration and reaction.

‘The Gays’ again, March 1983. Remember gay bars?

For the hard of thinking who have adopted the popular trend of confusing criticism for censorship, that couldn’t be further from the truth. To think differently about the past is not to “cancel” it, and satire as criticism is not above criticism itself. But I do find it fascinating how Private Eye has become such an object of affection for many British people, and why so many people regard it as a progressive organ. I think Private Eye has to be seen within a very British type of centrist politics, balancing a certain affection for the culture of the traditional stratified class system, the belief that there is such a thing as a patrician class, with a sense that critique is possible. It’s telling that a lot of the humour of the Eye relies upon understanding long-running in-jokes about “Ugandan discussions” and “page 94”. They are traditions in themselves, understandings ones inherits, like I did, where just knowing the tradition confers a sense of belonging. In that sense, the magazine is very much part of that public school, Oxbridge and Westminster culture of tradition as a tool of inclusion and exclusion.

Humour is often weaponised like that in the UK. Demands to be able to “take a joke” and “be a sport” are frequently abused in order to maintain insiders and outsiders; you’re allowed in if you’re willing to take the humiliation. It’s telling that, reviewing Tom Driberg’s posthumous memoirs, Peter Cook described him as a “poof with a sense of humour”. Not like the others who can’t take it (a joke, I mean). Yet anyone who’s put up with such a thing knows it has limits, keeping the humiliated constantly under threat of ejection. They also know that the humiliators can rarely take the joke themselves. Once I began to recognise those same schoolboy tactics in Private Eye, even the worthwhile journalism couldn’t take the bitter taste from my mouth. After a couple of decades of Have I Got News For You, you might start to wonder who is taking the piss out of whom. Some of the most objectionable characters in British political life have managed to achieve high office by first manifesting themselves as satirical figures in their own right. By becoming jokes, they preempt the disciplining power of the joke, and can rise to positions of power almost entirely on the back of the laughter. They might seem like the fool now, but before you know it they’re the Prime Minister and the Leader of the House of Commons, and scrutiny and oversight disappear beneath their pratfalls and pranks, and 100,000 British people are dead and the food is rotting at the ports.

You come to understand that the class system soaks into everything in Britain: how, at the top, they’re all essentially the same. The socialists are all aristocrats, the satirists are all bullies. Everyone is related to each other, or went to school with each other, and all are invested in keeping the class motor running. I myself went through a process that I think is a common disillusion. As an socialist eighteen year old, full of rage, you think Britain is a cesspit of conservatism, ruled at the top by a parasitic monarchy, where everything is rigged in favour of the rich. You think Britain is a closed shop where an Oxbridge elite perpetuate a system of patronage, of jobs for friends and the children of friends, where mediocrities rise to fame and fortune and where those who are talented but aren’t rich and white and usually straight and male rise only as performing seals or in order to line their pockets or flatter their egos. You think Britain is only a simulation of a democracy, where opposition is tolerated only so far as it shores up the establishment, tarts up the place to look a bit more modern, or where criticism is allowed only as an escape valve, to release pressure, where satire is a jester to a court that laughs then continues just the same.

Then you grow up a bit, and realise, of course, things are a little more complicated than that. Change is a slow process, realised in incremental steps that might seem invisible in the short term. Negotiation is the British story, the slow accretion of progress, the winning over of heart and mind. You get over your youthful idealism and realise that, while change is slow, the process does perhaps work. Not ideally, and not every time, but the power elites that once dominated British culture and society are seeing their power eroded in favour of a more open, egalitarian, and democratic national culture. Then you grow up some more, and realise you were right the first time, and the joke isn’t funny anymore.

Thank you again to all my subscribers. Please feel free to forward to anyone who might be interested. For those just visiting, I send out a newsletter/podcast a week to paying subscribers — for less than $5 a month — and one a month for free subscribers. You can subscribe here, and, if you like it, please hit the like button. It helps other people find my newsletter.