People describe Private Eye as a British institution, and I suppose they mean that as a compliment. The satirical newspaper, founded in 1961 as an antidote to Punch during the “satire boom” of the 1960s, was something I became aware of on the cusp of my teens. It’s a strange moment in a child’s life when they begin to make sense of the conversations that happen around the dinner table, the idea that the spluttered utterances from your mother or father listening to the radio news in the evening might belong to a sort of separate sphere of events. My father was working in Spain during the 1997 General Election, and I was travelling with him. The morning after the poll we parked up outside a service station somewhere in the Basque Country, and I remember the sharpness of the freshly squeezed orange juice — a novelty to me at the time — and the thick chunks of potato in the tortilla as he returned from the news kiosk to join me and his workmates in the cafeteria. He was clutching a Spanish newspaper and could barely hold himself down to the bench as he repeated to us, hooting, “la muerte del Thatcherismo! Brilliant! La muerte del Thatcherismo!” I thought he may never come down.

There were a couple of family friends who we’d visit down south every summer for a few days, people who seemed to relish both political argument and the strange, bitter humour that comes with a world of such cruelty and cant. I remember the sheer magnetic force of being 11 or so and seeing the energy of this type of humour, the drunken, roaring laughter that set the world to rights, past my bedtime and echoing up the stairwell where I lay and listened. While my mother was extremely politically attuned, it felt like her thought and action was conscientious, ethical, coming from her own parents’ background within the tradition of teetotal Lancashire nonconformists, and owing more to Methodism than to Marx. This attitude soaked into our own Quaker family home. This was something different, and my excitement at encountering it, at encountering these intoxicating isms so loaded with meanings and weaponised laughter, was made concrete by the fact that in their house I first read Private Eye. It was everywhere; recent editions on their kitchen table, last years in the downstairs toilet, annuals in the upstairs toilets and copies and books going back to the 1960s on their shelves. I might not have really understood who ‘SuperMac’ and ‘Grocer Heath’ were, but I got the intent of the jokes that seemed, to a young mind, like a cutlass slashing across the wind. Wishing to encourage my nascent interest in politics, and then, later, wishing to complicate my rigid, Manics-fuelled teenage Leninism, my mum would buy me the Private Eye annual every Christmas, where my brothers got FourFourTwo.

“Grocer Heath & his Pals” by John Kent, Private Eye, May 1970

That’s a long-winded way of explaining how I got confused into thinking Private Eye was somehow radical. I was thinking of this early relationship I had with the Eye, as it’s known, while working on some research recently. Regular subscribers will be aware I’ve been looking at the relationship between espionage and homosexuality in the UK, particularly in the immediate postwar period. You might think that finding out the actual details of such matters are complicated, giving the secrecy implicit within the security services. In reality, finding out the facts is relatively easy. What is more difficult is finding out public attitudes and opinions to homosexuality at a time when public discussion of sexuality was so much more limited, and couched in euphemism. When, in 1957, the government convened a committee to research criminal offences around homosexuality and prostitution, even the committee itself referred to its subjects as “Huntley and Palmers” rather than “homosexuals” and “prostitutes”.

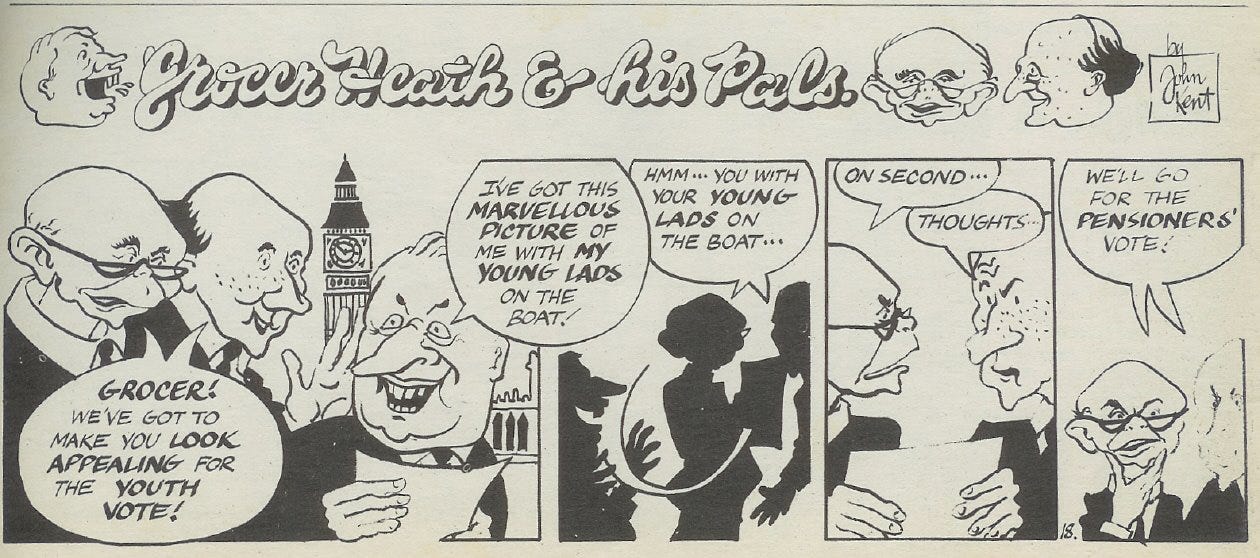

Detail from “How to Spot a Possible Homo”, Private Eye, May 1963

One organ unafraid to talk frankly about homosexuality even in the early 1960s was Private Eye. As espionage scandals involving homosexuals were in the news in the early sixties, thanks to both the defection of Burgess and Maclean and the Vassall Affair, there was a string of spoofs, features and cartoons in the magazine focused on the subject, some, such as this one from May 1964 illustrated by the late Willie Rushton, better than others.

Details from “More ‘Buggers’ Exposed, with cartoon by Willie Rushton, May 1964

From its earliest days in the ‘60s homosexuals, or, in the Eye vernacular, pooves, were a frequent subject for the magazine, and I’m afraid to report that the jokes rarely, in the contemporary vernacular, punched up. Often the humour was tied to the presence of a closeted public figure who wasn’t generally referred to as gay in the media, but which was nonetheless an open secret, such as the Labour MP Tom Driberg or the Tory MP, and later Prime Minister, Edward Heath. Here’s a cartoon following the death of Tom Driberg in 1976, playing on his legendary patronage of the gents’ loos as a cottager.

Cartoon by Nicholas Bentley, Private Eye, October 1977.

Whether they’re funny or not, and whether they’re cruel or not, Eye’s cartoons can sometimes be quite useful in thinking about the past. For a start, I’m not sure I entirely buy into the idea that “punching down” automatically makes a joke unfunny, not least because the idea of up and down is contextual. To reach again for a contemporary vernacular, perhaps an intersectional approach to satire is useful here. If Edward Heath was a homosexual, does that make him “down”, and jokes that included reference to his closeted sexuality inadmissable? Sometimes it is exactly the cruelty that can make a satire so perceptive in its evisceration of its subjects. Wildly unpopular though it is to admit it, it’s the reactionary moralism and social conservatism of Evelyn Waugh that makes him, to me, a writer who can so accurately observe and mock his own society, and the holes in novel ideas. Your tastes may vary.

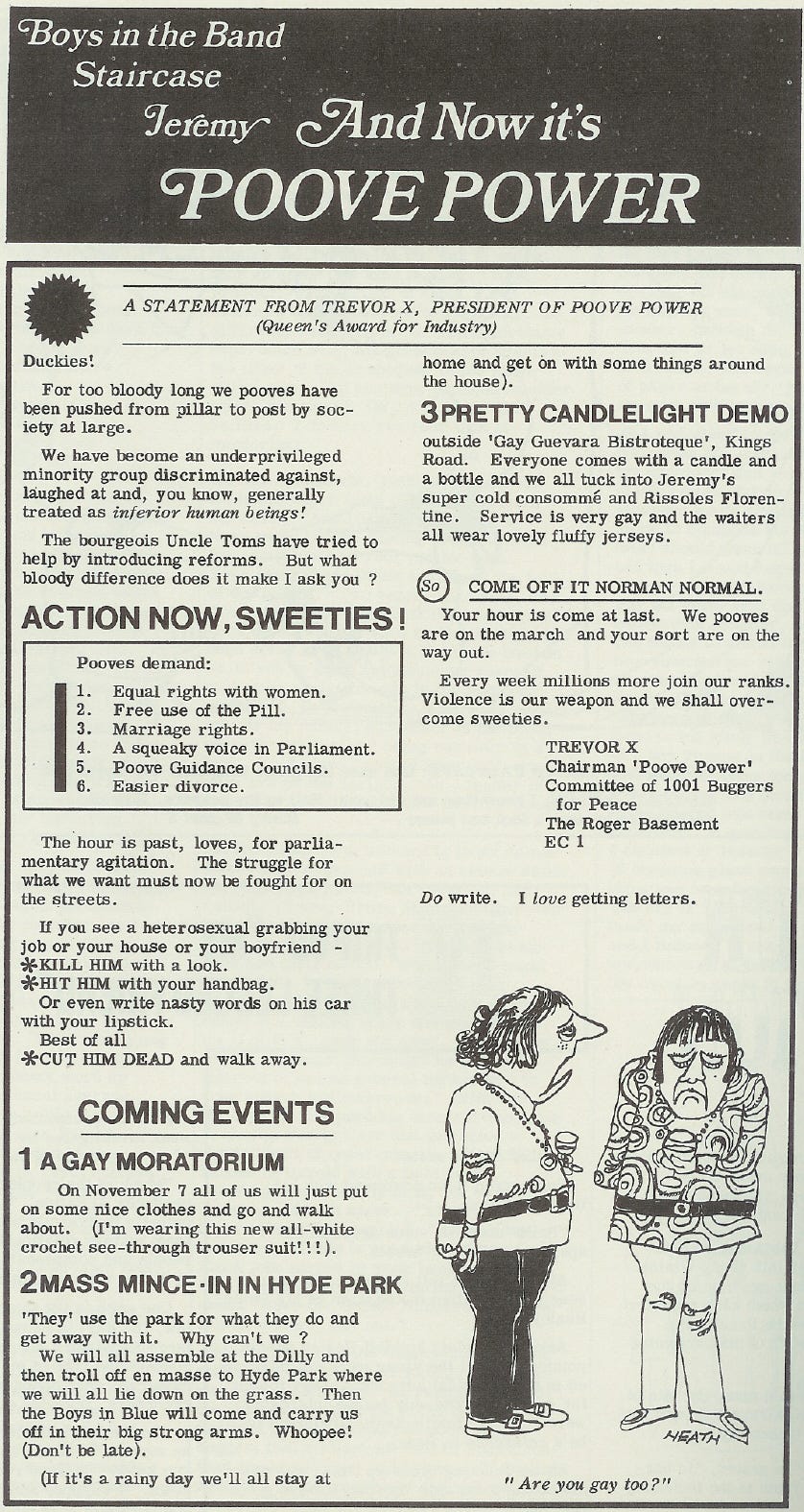

An example of this would be this extremely homophobic page from Private Eye in 1969, probably written collectively an anonymously (as many Eye jokes are) and illustrated by another problematic fave, cartoonist Michael Heath. It parodies the Gay Liberation Front and rising militancy within the queer community at the time, and illustrates perhaps why Eye’s coverage, produced as an immediate response to news and making satirical comment upon it, can be so useful. This page was produced just 6 months after the Stonewall Riots, and 5 months after the foundation of the Gay Liberation Front in the US. Indeed, it was produced almost a full year before the Gay Liberation Front was founded in the UK. It documents, therefore, wider social attitudes and responses to the idea of a gay militancy, and demonstrates how the idea of gay people even being militant was a direct challenge to mainstream ideas of homosexuality at the time. This is perhaps the moment where the old notion of what a gay man could be — bourgeois, depressed, unserious, fundamentally unsuited to political militancy — came into contact with the newer ideas of gay liberation. The humour is extracted from the very political conflict that was emerging at that. It marks a turning point, too, for representations of gay men in the Eye, especially by Heath. Before, gay men were paisley-adorned, lipstick-wearing, usually middle-aged and always tragic pooves. Within a decade, however, we see them depicted far more frequently as younger, cruisier, denim-clad, mustachioed gays.

There’s another aspect that’s useful here, and that complicates the idea of punching up and down. Part of the humour of this strip is derived from the idea that the GLF are taking the language of both anti-colonial and feminist struggles at the time. The parody open letter is signed by “Trevor X”, a reference to the black militants in the United States such as Malcolm X who replaced their surnames, derived from the surnames of those who enslaved and owned their ancestors, with “X” to indicate their unknown African names. The list of demands, meanwhile, is clearly a parody of the demands of the womens’ movement of the time; the demand for “Equal Rights with Women” is a joke about demanding the right to sleep with straight men. While the mockery of these imitations of the demands of Black power movements, womens’ movements and anti-colonial movements is clearly homophobic and cruel, it does raise useful questions. What does it mean that the Gay Liberation Movement explicitly used the names and rhetoric of anticolonial and feminist struggles while at the same time failing to adequately challenge racism and sexism within its own ranks, a situation that ultimately led to its own collapse? What are the implications of mainly white homosexual men and women, but largely men, in the US and UK adopting language that seems to claim parity with the experiences and struggles of Algerians fighting French colonialism, or Vietnamese fighting American imperialism? While the entire joke revolved around the humour of the idea that pooves could ever emulate the masculinity of independence fighters, and is therefore deeply homophobic, it also reflects the idea that the claim of parity is also absurd, a idea that has a point.

“Your Poove, Sir”, Willie Rushton cartoon, Private Eye, 1964. Wonderful.

The homophobia that underpins what we might call pre-liberation Private Eye —a mockery of a queer culture and identity that emerged in London between the wars, one recognisable in the work of Quentin Crisp — is a reflection of its class roots. The publication emerged out The Salopian, a magazine produced at Shrewsbury School, a British private boarding school, by four schoolboys: Richard Ingrams, Willie Rushton, Christopher Booker and Paul Foot. Ingrams and Foot both went to Oxford University after school, and Booker to Cambridge, an Oxbridge fate Rushton was spared. Some of the lads reunited in London to start the magazine backed financially by other Oxford friends shortly after, while still in their early twenties. Its editor was Richard Ingrams, whose homophobia was not just the casual homophobia of its time but a deeply held, almost pathological conviction in the perverted nature of homosexuality that he has nurtured deep into this century, often printed up by The Observer (and more on them later). The magazine was funded and later owned by satirist and Cambridge graduate Peter Cook. Cook was the founder of the satire club The Establishment, just yards from the Private Eye offices in Soho, which opened in October 1961, the same month the magazine launched. Cook was a key figure in the so-called Satire Boom of the early ‘60s, where alongside the Eye and The Establishment sat the comedy revue Beyond the Fringe and the BBC TV show That Was the Week That Was. The period is now memorialised in the imagination of the same section of society as a landmark in the liberalisation of British life and the start of the erosion of the culture of deference.

The public schoolboy vision of homosexuality that set in at the Eye seems peculiarly English and upper-class. It is at once both puerile and worldly, accepting pooves as an ever-present fact of public life, yet seeing them, and it, as a deep source of ridicule. It lacks the disgust and outrage that Mary Whitehouse had for it, yet almost holds it in lower esteem. It is a naughty joke. Both those who do “get caught”, and those who are open about it are sources of amusement, as though they should have grown out of it by now. And perhaps that’s the point; it’s a view derived from a childhood where situational homosexual behaviour was institutionalised as part of private school life. Thanks to the widespread prevalence of childhood sexual abuse in the British education system, it was also something associated with authority figures, hypocrisy, and privilege. Writing about his schoolmaster at Shrewsbury, Anthony Chenevix-Trench, Paul Foot recalled “He would offer his culprit an alternative: four strokes with the cane, which hurt; or six with the strap, with trousers down, which didn't. Sensible boys always chose the strap, despite the humiliation, and Trench, quite unable to control his glee, led the way to an upstairs room, which he locked, before hauling down the miscreant's trousers, lying him face down on a couch and lashing out with a belt.” In his obituary of Foot, Nick Cohen (also an Oxford grad and Observer columnist who contributes pseudonymously to the Eye) said “Exposing [Chenevix-Trench] in Private Eye was one of Foot's happiest days in journalism. He received hundreds of congratulatory letters from the child abuser's old pupils, many of whom were now prominent in British life.” I’m not sure you can detach this singular status of homosexuality as both abusive predatory threat and teenage sexual solace within the private school system from upper class cultural perspectives on gay people. Exposing the powerful as secretly homosexual, and highlighting their engagement in degrading sexual habits like cottaging or sex with guardsmen (another preoccupation of the class position) was both humour and revenge for this generation.

Private Eye, January 1968

These preoccupations came together in a genuinely important journalistic landmark in Britain, for which the Eye should be applauded, a piece of important journalism that probably wouldn’t have found publication were it not for the Eye’s homophobia: the Thorpe Affair. The tale of Jeremy Thorpe’s descent (if you want to look at it that way) from respected leader of the Liberal Party to his trial for conspiracy and incitement to murder is a long and tortuous one, a tale that has its own lessons to tell about British relations to class and homosexuality. If you are interested in that, we tell the full story on this episode of the podcast Bad Gays. Thorpe was a ruthless political operator who had risen to lead the Liberal Party while at the same time engaging in a number of sexual affairs with younger men, one of whom, a stablehand named Norman Scott, had become “troublesome”, making increasing demands for assistance from Thorpe. It was later alleged that Thorpe then conspired with two associates to have Scott bumped off, as well as liaised with party donors to fund the hitman operation. His position within the party made him almost impossible for newspapers to touch, such was the discreet code of silence regarding homosexual affairs of the rich and powerful. Scott had taken his allegation to social security, to lawyers, the press and even to the Liberal Party, but had struggled to have his side of the story heard, partly on the grounds that he was read as an attention-seeking queer. But when a gunman attempted to shoot Scott on moorland in Thorpe’s constituency, and ended up killing Scott’s dog Rinka, a police investigation did begin.

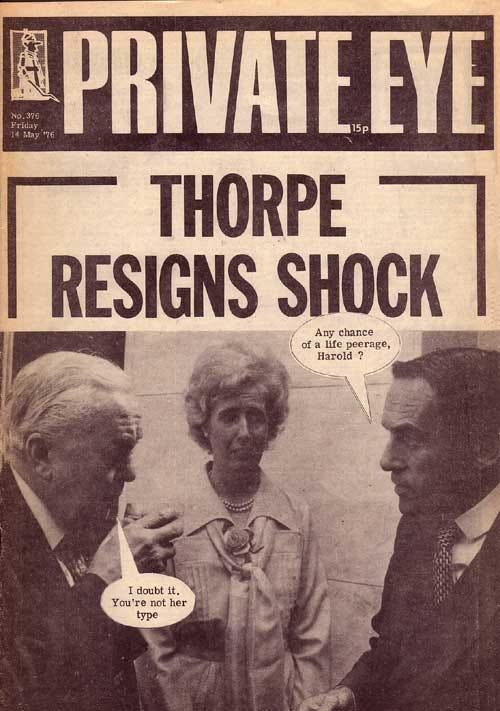

Cartoon by Marc, Private Eye, February 1976

It was Auberon Waugh, the son of the aforementioned Evelyn and regular contributor to Private Eye, who was one of the few to cover the story, publishing a series of heavy innuendos. While other newspapers declined to publish Scott’s earlier allegations (a stance also taken by Ingrams for a while, regarding them as likely blackmail), in the end Waugh was the little boy who pulled his finger from the dyke, as it were. He ended his first piece on Thorpe by saying “My only hope is that sorrow over his friend’s dog will not cause Mr Thorpe’s premature retirement from public life.” While the hitman, Andrew Newton, was jailed for two years, he didn’t implicate Thorpe, who resigned but denied all and remained an MP. Former Prime Minister Edward Heath must have been glad of the reprieve, as as a confirmed bachelor (a position, at that time, no longer beyond heterosexual reproach) he had long been the subject of the Eye’s innuendo, which heavily implied he was somewhere between homosexual and paedophile, and split the difference.

Private Eye cover, 1976

This was typical of the light and mocking tone of Waugh’s columns, but the case was also taken up by a more serious journalist, an early contributor to the Eye, Paul Foot. Foot was a fellow graduate of Shrewsbury School and Oxford University, and was a member of the powerful Foot family, but his politics was far to the left of most of the magazine’s staff. He was to make a name for himself as a campaigning investigative journalist, particularly focused on miscarriages of justice such as the case of the Birmingham Six. When Newton was released from prison the police reopened the case. Foot published a report in the Eye of Thorpe’s interrogation entitled “The Ditto Man” and Thorpe sent the Eye a writ: one of many occasions in which the powerful have attempted to use Britain’s libel laws to silence the paper, which highlights the important role it has played at times. The paper was not intimidated, and soon the story broke, leading to Thorpe’s trial, which Waugh would go on to cover in a book.

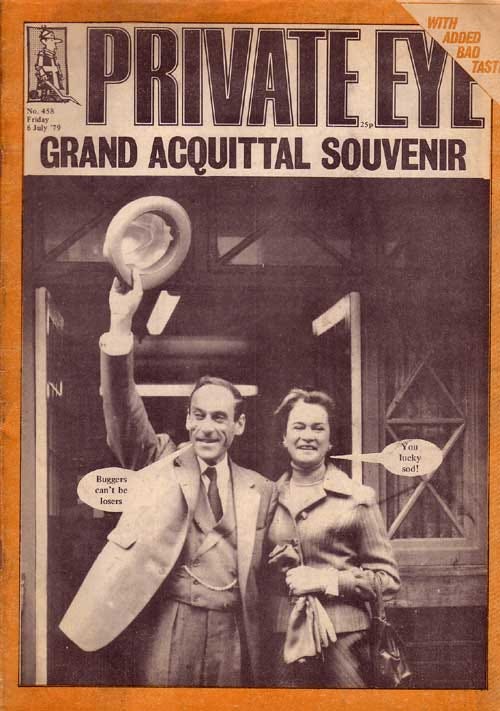

Private Eye cover, 1979

In the end, Thorpe was, quite extraordinarily, acquitted, helped by the highly partial summing up of the judge, Justice Cantley. As well as the aforementioned episode of Bad Gays, there’s an enjoyable drama series about the case written by Russell T Davies. However the cultural impact of the case will be forever tied to a parody of Justice Cantley’s summing up, performed by Eye owner Peter Cook just days after the trial came to a close, entitled Entirely a Matter for You. Mocking the biased summing up, Cook produces one of the masterpieces of British satire, but in it we see a number of the recurring tropes from the Eye. Norman Scott is rechristened Norma, Thorpe’s wife recast as his husband (a joke that still had at least another decade in it, replaying during the introduction of Section 28, which banned promotion of “pretended family relationships”) and, of course, the legendary accusation that Scott was a “self-confessed player of the pink oboe”. What’s startling is the general lightness with which the whole thing was portrayed. Despite the gravity of a case in which an elected politician allegedly conspired to commit political murder, the mere presence of homosexuality coats the coverage in a thick layer of schoolboy sniggering, and Scott, a man rightly aggrieved and very nearly murdered, became little more than a sad punchline.

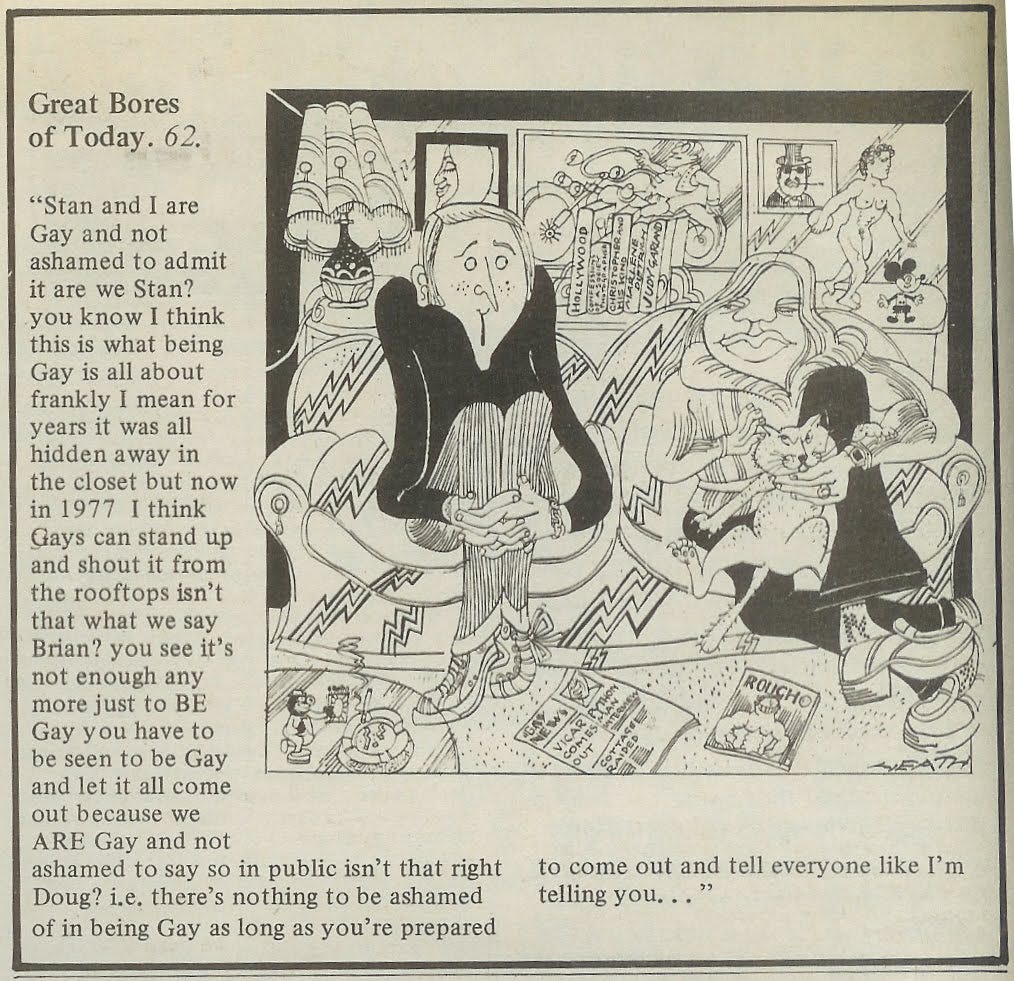

This schoolboy approach was to continue to mark Eye’s coverage of gay men particularly into the 1980s. The representation might have changed —the rouge wearing older pooves replaced by leftist gays — but they remain a target for cartoons that revolve around little more than the fact they exist. In a strange way, these cartoons can be most useful in trying to get a feeling for the sort of attitudes held at the time. Watching It’s a Sin this week, I was thinking about how representations of homophobia in the past are often characterised by violence and aggression. Depictions of responses to the AIDS crisis, for example, often revolve around the idea that heterosexuals were fearful and disgusted by gay men, and queer bashing, spitting and other extreme forms of violence. But much of Eye’s homophobia is marked by a sort of world-weary derision. Humiliation and abjectification is must rarer in representations of historic homophobia, but were tools in the suppression of queers that were much frequently used, and to just as destructive effect. It’s something you find frequently in the writings of other privately educated, Oxbridge writers, such as Christopher Hitchens; a sort of derisive mockery of homosexuals which never borders on appearing fearful, or disgusted, or morally opposed to homosexuality per se, and is often justified on the grounds that they themselves have had homosexual experiences at school, or excused by the fact that they would be gay were it not for the fact that gay men won’t sleep with them. This strikes me as a poor justification for a joke not funny enough to carry the slur. Much in the Eye archive that passes for satire is little more that a perpetuation of this culture of humiliation.

Great Bores of Today comic strip, illustrated by Michael Heath with text by Barry Fantoni and Ingrams.

“A joke not funny enough to carry the slur” is perhaps a useful way to characterise Eye’s gay content as we go into the 1980s, when, during the AIDS crisis, accurate reporting of queer life became an issue of mortal political import. But the ‘70s still had a few punchlines left up its sleeve, with the “outing” of the art historian and Surveyor of the Queen's Pictures, Sir Anthony Blunt, as a member of the legendary “Cambridge Five” Soviet spy ring shocked the country. The case recalled many of the jokes in the Eye in its early years, when the Vassall affair had provided the boys with a bunch of amusing comparisons between the closeted worlds of homosexuality and espionage.

Another favourite for me: Heath again, Private Eye, January 1980

However this time Private Eye had a front row seat. In 1979 journalist Andrew Boyle published a book about the spy ring, entitled “Climate of Treason”, in which Blunt featured, but under a pseudonym “Maurice”, after the eponymous homosexual protagonist of the book by E.M. Forster, published earlier that decade. Blunt demanded to see a copy of the manuscript from the book’s editor, essentially outing himself. The Eye published the story, and on publication of the book, named Blunt as “Maurice”. I cover the story and Blunt’s fascinating life in detail in this episode of Bad Gays. It was an incredible scoop for the magazine, worthy of a major broadsheet, but for the Eye the combination of homosexuality, espionage and monarchy was an irresistible threesome for Private Eye. Like in the Thorpe case, they revelled in the pleasure of puns.

Yet the era of queens and pooves was drawing to a close. Increasingly militant gays had begun to organise and the new left were putting the demands of lesbians and gays into the mainstream political sphere, where they were gaining actually political power, especially within the Greater London Council (GLC). Meanwhile the impending humanitarian disaster of the AIDS crisis provided plenty of laughs.

Read Part II of “Poove Power”, looking at how the rise of the “loony left” gave new ammunition for Private Eye to satirise gays, but how gays in schools and the AIDS crisis saw the Eye fuel an increasingly homophobic moral panic that lead to government crackdowns on homosexuals, here.

I am hugely grateful for, and indebted to, the work done by the blogger ukjarry in archiving many of the images used in this piece on his excellent blog StreetLaughter: A Gay Cavalcade of Comic Stereotypes, which looks at fifty years of comic representations of gays on TV, film and in print. Please do check it out, you won’t be disappointed.

If you want to read the second part of this essay, I will be releasing it to my paying subscribers next week, although I will make it more widely available at a later date. If you would like to get it hot for the press, please do consider upgrading your subscription for just $5 a month.