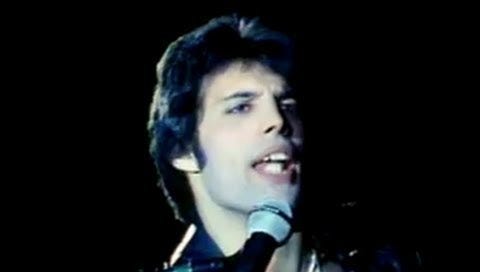

Do you think of Freddie Mercury as a gay icon? If so, you are, statistically speaking, straight. I’m sorry to be the one to break the bad news to you, but that is the way the cards have fallen. It’s the strange legacy of a man who, for a brief period, stood astride the world as a rock icon who bristled with sexual charisma, yet never quite performed the role of a sex god. Perhaps it was his curious mix of masculinity and coquettishness, his rich, sissy camp mixed with his broad-chested physical control and dominance, that confused people. To me, the contradictions are strange, alluring; the combination of exuberant gestures and exaggerated dick-grabbing masculinity is personal catnip. Yet those contradictions are what lends Freddie his odd afterlife; for straight people, it’s a disorienting reinforcement of the gay man as gender deviant and sexual predator, while for many gay people, well, there’s something tacky, embarrassing, something played out about Freddie Mercury. True, it’s a category error to think that gay men ever become gay icons themselves: that’s a position generally reserved for women. Yet, at a certain point in his life, Freddie was probably the most famous leatherman in the world, and at the centre of a cutting-edge gay sex subculture that continues to fascinate and inform gay culture today. But Freddie? Not so much. His absence from a gay nostalgia that touches on so many parts of his life is striking.

This September would have marked Freddie’s 75th birthday. We can only imagine the scale of the affair; his birthday parties are part of rock mythology for their scale and debauchery. But he didn’t live; watching the news report of his death, with archive footage of him descending the airstairs from a plane, was one of my earliest memories. Like many who die young, at that moment his creative life stood still, unable to answer for itself. Who he is today is not just the sum of how he lived, but of the moment he died, how his life was assessed and was interpreted, and the legacy of that time, when homosexuality had being almost synonymous with the AIDS crisis for many. We were a Queen household thanks to my elder brother, who introduced the band as the first music we listened to that wasn’t my parent’s choice. Throughout my childhood they were sort of omnipresent, their Greatest Hits I and II burnt into my memory such that even today, when one song comes to an end, the intro to the next finds its way to my lips and I start humming. As a teenager, I had a poster of Mercury on my wall, a decade after he died. Yet by that point I rarely listened to them, and today, never. It took me by surprise, then, to feel deeply moved when I watched Bohemian Rhapsody, the recent biopic of Freddie’s life with Queen. Specifically, I was moved to fury. It felt disgusting to watch, as though in watching it I was somehow complicit in the way this story was being told.

I clearly felt deeper about the subject than I had realised. What was missing in the way Freddie is today depicted? Why, throughout my life, have I kept returning to Freddie Mercury, as a performer, as a gay man, and why, thirty years after his death, is his strangeness, his performance, his sexuality, his gender, more interesting to me than ever? And why do so few other gay men seem to feel the same? Why is he remembered, or rather forgotten, in the way that he is? How did Freddie Mercury become the straight person’s idea of a gay icon, while simultaneously becoming excluded from the actually-existing gay canon?

At its core, the problem is that in both instances Freddie is still owned by tedious straight men, both ideologically and literally. Ideologically, he is owned through his association with Queen, whose emergence within the notoriously macho fanbase of classic rock survived Freddie’s flamboyance from the start of their career, and won them a legion of rock fans. Queen may always have been an anomaly within that scene, able to switch between pop, rock, and metal registers, but their roots remain within a music that was built for straight guys, a scene that often betrayed an assertive anti-queer, anti-black reaction, typified in the “Disco Sucks” attitude of the late 70s. Freddie was always a rock star, not a pop star, and for years, liner notes for Queen albums included the proud disclaimer: No Synths! While musically Queen would not be unshaped by Freddie’s encounters with disco, it’s as a rock band that they built and maintained their fanbase.

Furthermore, his legacy is still literally controlled by straight men; after Freddie died, the band continued, and continues to this day, existing as a sort of tribute band to itself. As well as new albums released and remastered using previously unreleased Freddie vocals, the band (minus John Deacon) has also built a new career on top of their historic legacy, with a live stadium show that continues to draw vast crowds and is fronted by a string of alternative Mercury replacements, notably Paul Rodgers and Adam Lambert. As well as the live show and albums, the band’s franchise has extended across platforms, including an ill-fated early video game, Queen: The eYe, cameos on X Factor and in the Olympics Opening Ceremony in 2012, a Queen West End Musical, and even a Queen ballet. Some people will see such cashing-in as a distasteful abuse of Freddie’s memory, out of tune with his stage performance, which relied so much on his idiosyncratic and unreproducable personal charisma; in reality, cashing in was always the Queen story, from their soundtrack albums to their unapologetically crowd-pleasing stadium anthems, to their notorious breaking of the South African anti-apartheid cultural boycott with their Sun City shows.

I’m neither fan nor hater enough to be particularly exercised by this project to squeeze every last pound from the brand, but it’s an interesting example how the management and control of already existing intellectual property, and the right to exploit its rewards, continues to misshape our cultural landscape. Holding the rights to the music gives the band, and especially its two remaining original members, Brian May and Roger Taylor, the key to shaping the historical memory of Freddie; the urge to protect the brand, which continues to produce massive value over and above royalties, has surely shaped the way he is remembered.

The biopic of Mercury’s life, Bohemian Rhapsody, is the most egregious example of how control of the intellectual property shapes just how a story is told. It’s no secret that Sacha Baron Cohen, who had long discussed his desire to play Freddie, left the film after the band pushed for a much more PG production. His replacement, Ben Whishaw, also quit after allegedly disagreeing with the direction of the script. The urge to maximise potential profit with a lower certification, and to give the film the broadest possible appeal, produced a film which continued down the long tradition of telling a straight story about Freddie, especially regarding his sexuality. In doing so, it reverts to a heroic mode for Mercury, casting him as a man who must overcome some flaw in his character to realise a greater destiny for himself; in this case, as in much of the Queen hagiography, the flaw is homosexuality, and the destiny is rock.

There was a golden time before homosexuality, when the band lived a full-throated rockstar dream with girls and touring and booze and girls, and Freddie was dating his lovely girlfriend, Mary Austin, and God was in his heaven and all was right with the world. It was into this prelapsarian paradise that homosexuality emerged, first destroying his relationship with the woman who would have been his wife, and then almost destroying the rock. In this story, Freddie’s same-sex desire leads him into a descent into the netherworld, where he is transformed by sodomy. When he re-emerges, penitent and blinking into the world, he brings with him some great creative secret that transforms him, and the band. But he cannot go unpunished; in this story (and it remains a common one), guilt is the natural bedmate of homosexuality, and AIDS is depicted as a metaphor for that guilt, the price of allowing yourself to be led astray.

It’s a terrible, reactionary, 1980s approach to both his creativity and towards homosexuality, yet Bohemian Rhapsody followed this narrative closely. Perhaps the most interesting scene is the one in which Freddie, played by Rami Malek, quite literally descends into the dark gay sex clubs of New York, places which are depicted as threatening, aggressive lairs of male sexuality, foreboding, with the threat of sexual violence or depravity just under the surface. It draws its influences from William Freidkin’s deeply controversial, homophobic, but good, film Cruising, in which a serial killer stalks New York’s gay BDSM scene; dark shots of Freddie walking through clubs pulse with house and disco music, enraptured by his own desirability to the men he encounters. Shots of the band rehearsing their 1980 hit Another Bites the Dust mix with montages of leather daddies leading men in masks through the heaving, sweaty crowds. It’s a trope for threatening gay desire that’s so well established that the Bohemian Rhapsody scene looks almost like a shot for shot remake of the famous “lebanese gay panic” scene from Kath and Kim, which was filmed 16 years earlier.

When Freddie returns, he, and the band, are transformed; his encounter with New York’s underground gay scene exposed him to the influences of disco and house music, and the creative output of other queer people of colour (the film seems to have an ambivalent relationship to Freddie’s ethnicity and downplays this link, perhaps influenced by Mercury’s own attitude). This much is true; from the point Mercury came out to himself and starting visiting gay clubs, he pushed Queen’s output in a very different direction from the hard rock they had made their name with; as Roger Taylor says in the film “We’re a rock and roll band. We don’t do disco.”

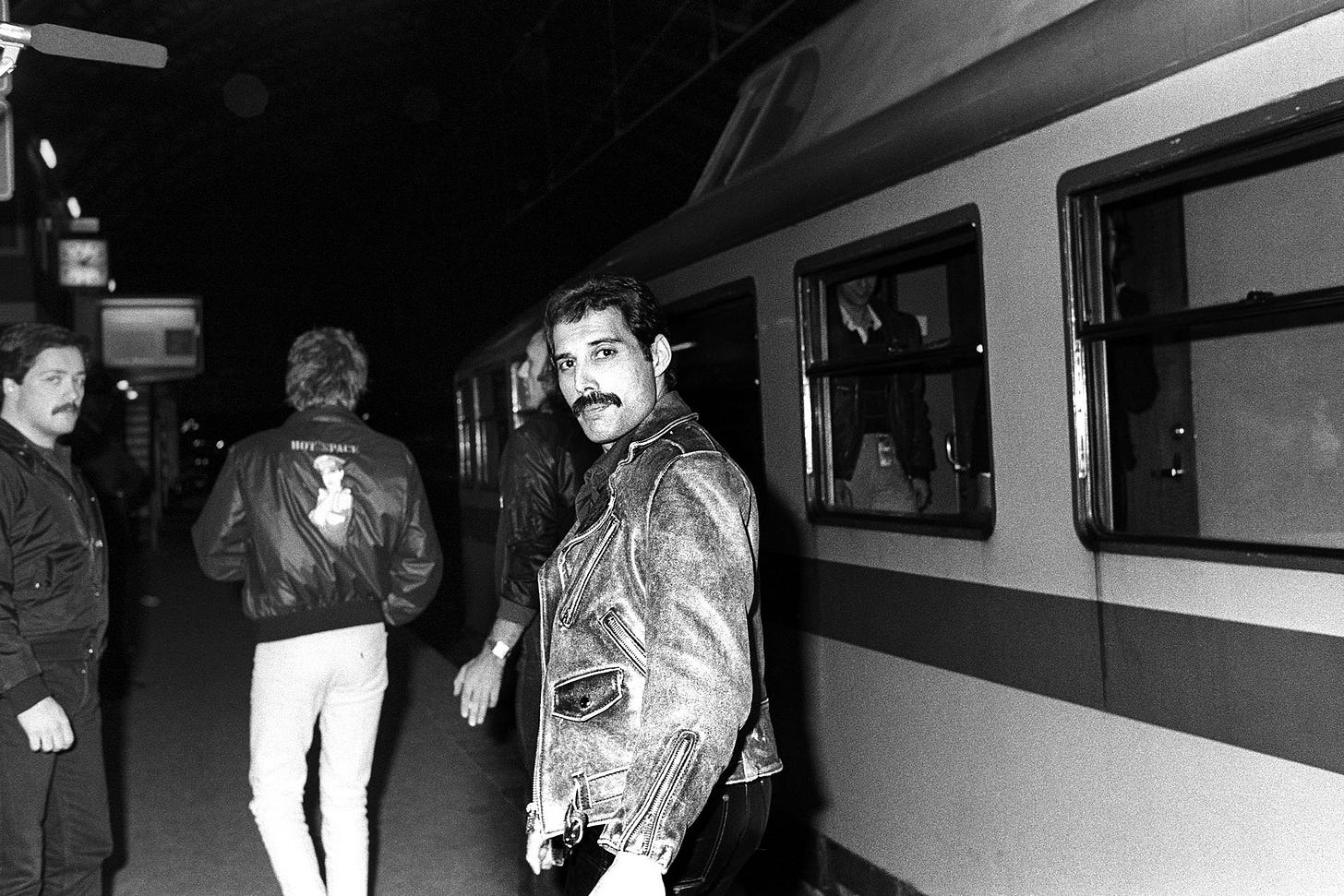

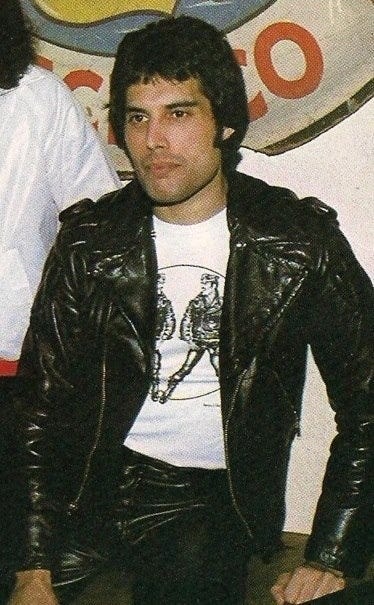

The influence wasn’t entirely appreciated by their fans. Their disco-infused 1982 album Hot Space was one of their least popular, even if it had been inspired by their huge 1980 hit Another One Bites the Dust. At the same time, Freddie’s image changed. The flamboyant 1970s rock god look of leggings, capes and long hair was replaced by a neat crop, big moustache and tight denim and leather around 1978. To anyone on the gay scene at the time, it must have been immediately obvious that Freddie was family; the look is a perfect representation of the hyper-masculine “Castro Clone” look that dominated urban gay centres in the late 1970s and early 80s. The look is so quintessentially the gay look of its time that you must wonder how anyone maintained the fiction that he was ever heterosexual, yet that’s the benefit of a hindsight that Mercury created; for many straight people the look became associated as the pantomime gay “look” precisely because they later associated it with Freddie who, just a day before his death, announced he was HIV positive and thus implicitly became one of the most famous gay men in Britain. Many others still maintain the fiction; as a teenager I recall a conversation with one of my mother’s carers who swore blind that his homosexuality was an invented slander after his death, and that he was a straight man.

In all these representations, queer culture, gay male culture, is an external world into which Freddie ventured, or was lured. His inability to resist it is depicted as his Achilles’ Heel, the fatal flaw that every genius has. His late coming out has perhaps perpetuated that story among gay people, too, as though he was deeply ashamed of his sexual orientation. This seems an unnecessarily unsympathetic read, as though the verbal declaration of homosexuality is the start and end of a publicly queer life. Asked about his sexuality later in life, the Mexican pop icon and heartthrob Juan Gabriel, another man who pushed the boundaries of a wordless queerness, would respond "Lo que se ve no se pregunta" -- “What can be seen doesn’t have to be asked.” Freddie’s late ‘70s transformation seems to me not so much an Orphean descent into the homosexual netherworld, as a flourishing embrace of the creative life that homosexual friends, and homosex, gave him. Can you really call someone wearing a Tom of Finland t-shirt beneath his braces and leather pants “in the closet” in any meaningful sense?

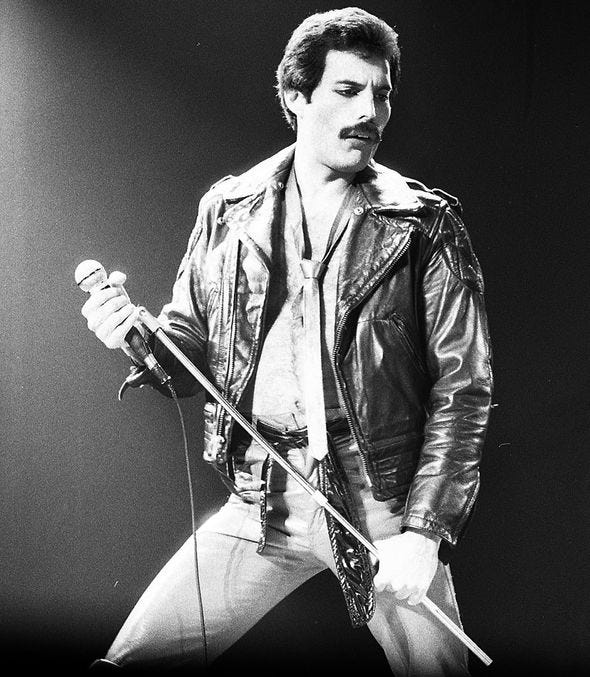

1980s Freddie is not a crumbling neurotic queer haunted by his own lusts. He is a sexual powerhouse of aggression, desire, and fucking, a leather-clad daddy taunting his largely straight audience with a combination of pelvic thrusts and hip-shimmies. His 1970s rock persona used his camp as a musical foil to heterosexual rock; now his entire register is homo, and the tension between top and bottom, dom and sub, masc and fem, becomes a motor for a sexualised stage performance that unleashes a confrontational persona that is wildly charismatic. Compare the strutting peacockery of his mid ‘70s Top of the Pops performance of Killer Queen - a mode that could be shared by any number of straight performers, from Mick Jagger to Rod Stewart - with his mid 80s Live Aid performance. Something has been unleashed; a fist-pumping, legs astride, arse-slapping physical masculinity, combined with an engagement in wider queer musical influences. Doesn’t the homosexual libertinage unleashed by the sex clubs - the bondage, the gangbangs, the drugs and the boys - actually mark a moment of creative awakening? Didn’t the libidinal power of the late 70s New York gay scene produce a burst of self-confidence in the performer that powered the band through the creative low points of the following decade?

The sad song told about Freddie’s libidinous life in New York’s gay underground seems something superimposed from outside, and retroactively. It is likely that during this time, Mercury became HIV positive, and it’s around this fact that, in my opinion, much of the difficulty people have in assessing his legacy occurs. As late as 2018 the book “Somebody to Love” told a dual biography of both Mercury and the HIV virus, a chapter at a time, creating in the reader the sense of an imminent fate as the stories move closer and closer to the point at which they join: New York in the late 70s and early 80s. Troublingly, the story being told in this manner creates a sense of inevitability towards Freddie’s sickness, something hard to disassociate from blame, as if, years before people were first recognised to be dying from AIDS, he should somehow have known such a thing was possible.

Blame continues to float around his memory; his death recast as a sort of collective tragedy for everyone else, and the specificities of his own life and death too indelicate to discuss. Homosexuality is cast as his hubristic flaw, the moment he pushed his desires for rock hedonism too far; indeed, sometimes it feels as though some Queen fans feel homosexuality stole Freddie from them, and robbed them on his future music. In the film Bohemian Rhapsody that’s certainly the case; Freddie’s enjoyment of homosex culture comes close to breaking up the band for good, stealing him from his rightful place, while a series of increasingly unpleasant villains who mislead the otherwise good-hearted if temperamental Freddie are all not only gay, but living manifestations of the sex culture he threw himself into.

Perhaps that’s to be expected, and par for the course; his established fans would have no interest in New York’s homosexual subcultures of the time, no interest in leather culture, and so of course they would find their heroes wholehearted embrace of his queerness alienating. His late, clone image became indelibly associated with his sexuality and his HIV status. Furthermore, Freddie’s death in 1991 was marked as the first death of a major rock star from AIDS, and as such was, for many people outside of marginalised communities affected by HIV, the first person they knew, they cared for, who had died of the disease. That was complicated; some of those people didn’t know he was gay, others loved him despite the fact, others knew but didn’t care. Sympathy and grief were sometimes mixed with fear and disgust.

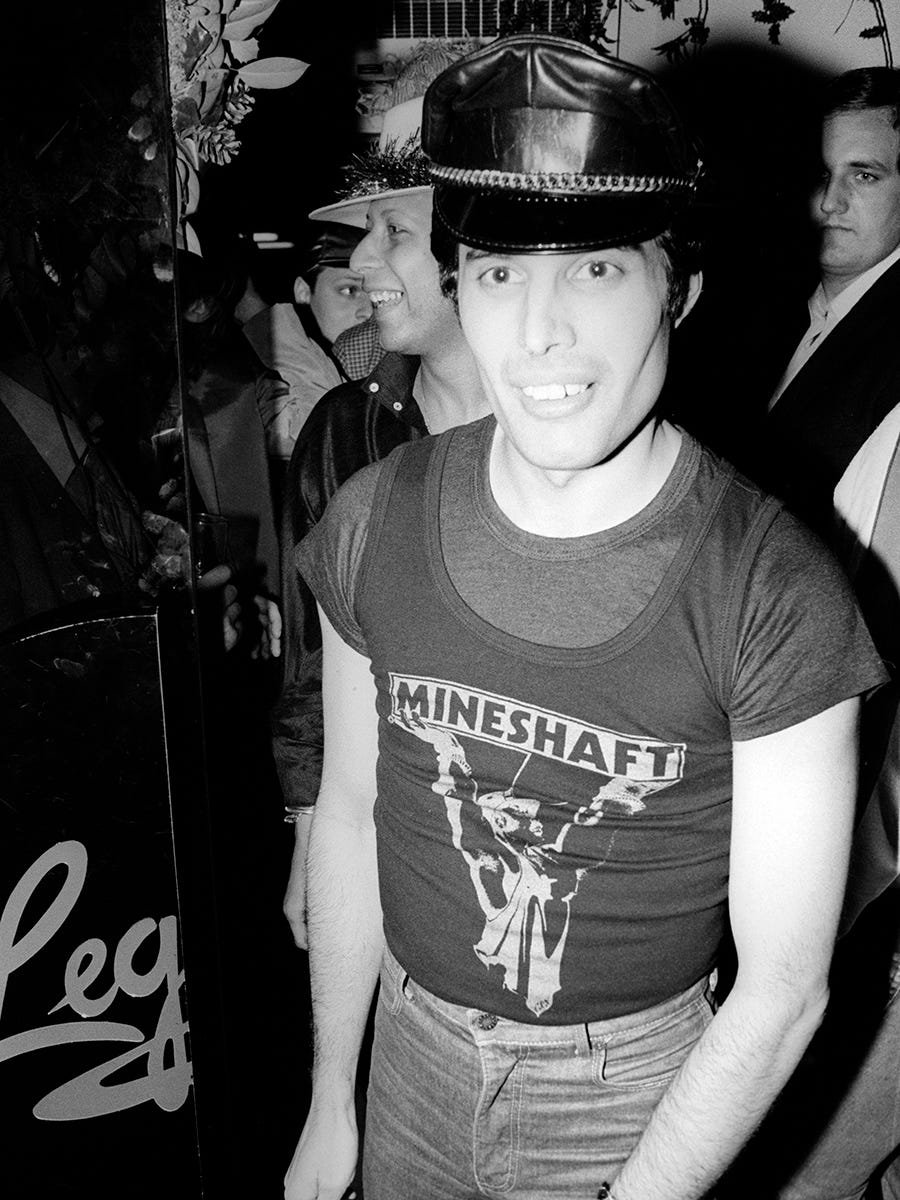

That is their business. But why does he still hold such an ambivalent position in the minds of gay men? I suspect upon his death, there was resentment from more explicitly out gay men that he hadn’t been more public, more vocal, both about this sexuality and his HIV status at a time when both gay people and HIV positive people were subject to an international hate campaign. For others, his music was what alienated them, fitting as it did into a much more mainstream, popular and rock world than many frequented. What seems strange to me, however, is how his life in the late 70s and early 80s is still so estranged from a wider understanding of the man. At the time, he was frequenting some of the most interesting and exciting gay clubs in New York, and engaging in era-defining sex cultures. He was a regular at The Anvil, whose fisting shows and crucifixions made it notorious, and where Cruising was filmed. In the late 70s he even wore a t-shirt from the legendary sex club Mineshaft for his performance in the video to Don’t Stop Me Now, beneath a black leather jacket, singing “Tonight I'm gonna have myself a real good time / I feel alive / And the world I'll turn it inside out, yeah / I'm floating around in ecstasy”. The clubs and sex were not the dark secret of his life, they were moments of heightened joy and pleasure.

In recent years, this period of New York’s gay underworld, alongside the piers and other cultural scenes, has become of increasing interest (and some would say fetishised) by a younger generation of queer men who see it as a complicated period of self-expression, sexual adventure and cultural experimentation, and as a world that was lost to the AIDS crisis. There is plenty to interrogate there, of course, but for now, I simply wonder why, when we list off the clientele of the Mineshaft, we see its importance in the cultural life of Robert Mapplethorpe, Annie Sprinkles or Michel Foucault, but not Freddie Mercury? This aspect of his life may be confusing, alienating, or resented by a wider straight audience, and liable to be downplayed or demonised by those who still profit off the band’s straight fanbase. But Mercury’s absence from a gay canon can’t be put down entirely to that. We are missing a trick in refusing to recognise that sexuality was neither a dirty secret to Mercury, nor a distraction from his career, but rather that his engagement in leather and sex clubs were a moment that revolutionised his life, opening him up to wider cultural influences, and inculcating in him such a powerful, self-confident sexual persona that meant that even in the depths of the homophobic 80s, one of the biggest, most popular artists in the world was cock-grabbing, fist-pumping gay leatherman. Does that mean nothing?

Thank you again to all my subscribers. Please feel free to forward to anyone who might be interested.

For those just visiting, you can subscribe here, and, if you like it, please do share on social media etc. It helps other people find my newsletter.

Paid subscribers get access to the entire archive of 80+ essays, including recent posts such as this essay on Fernando Pessoa, the European periphery and Barrow-in-Furness, this radio-visual essay on queer protest, and this essay on the remembrance culture around Walter Benjamin.

Randomly came across this - pardon the pun considering the content - and found it a magnificent read. Just thought I’d say thanks for expelling the energy to write it.

One of the absolute best interrogations of Mercury's life I've read. Your podcast episode on him was great, too. I appreciate the historical context and depth of thought.

I visited a "Hard Rock Cafe" a few months ago, and his representation in the realm of merchandise has been interesting to see develop. It seems as if they are making a more active effort to associate him with the mainstream idea of "gay pride". I wonder if that's a response to the phenomenon you refer to here.