I’d guess the first experience of fandom that I ever had was as the butt of a joke — Trekkies, that obsessive, slightly tragic group of Star Trek fans whose interest in the show was seen to have gone too far, and marked them out as nerds, weirdos. In the ‘90s, to be an obsessive fan was almost a secret shame. It’s perhaps unsurprising that fans of science fiction would be ahead of the curve. In an era of mass culture delivered through limited channels — a few terrestrial TV stations and the cinema — it wasn’t hard for fans to emerge, but for them to connect into a fandom took a good deal more effort. The explosion of the internet, streaming, and social media has allowed fans to coalesce, sharing interests, expanding narrative universes, writing fanfic, until they have become almost a cultural force in their own right, shaping commissioning and editorial policy at even major movie companies. Today, fandoms help structure how millions and millions of people watch TV, read books or see movies.

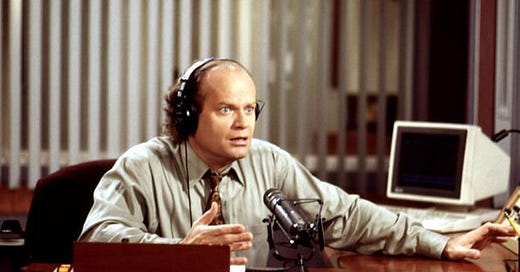

The closest thing I become to being a fan myself is watching Frasier, an American sitcom I first enjoyed as a kid and have rewatched all the way through a few times since. In the past couple of months, as lockdown has stretched my tolerance for anything, my attention span dwindling, I have wondered a lot about how writing, and especially writing a newsletter, relates to ideas of collective enjoyment, fandom, sustainable creative life, and more. I’m trying to shape those arguments at the moment, to understand how the internet has changed the role of the serial and the essay. But while I’ve been struggling to find the ability to put words onto paper (digitally), I decided I needed a regular daily writing practice: one that is outward-facing, for other people, people who enjoy what I enjoy. As the focus of that practice, I’ve started to write a newsletter about Frasier — an essay for every episode, in fact. You can read it here at Tossed Salads and Scrambled Eggs.

In the process, I’ve found a close examination of the TV sitcom has been extremely productive. It’s really amazing to see how something created by a collective, collaborative process has produced such a cohesive narrative form. As you go deeper, you discover long-running ideas that help build the characters into more rounded figures, and, perhaps unconsciously, you realise how local and national cultures — political, social, creative — manifest in the show. It’s a show about grief, and about loss, but also about class and how it’s upheld. It’s about how the traumas of childhood hang over to shape us into neurotic adults. And it’s about the attempt to come to terms with losing a way of life you thought you were owed — a pertinent tale for Americans today.

One thing I’ve noticed is how different it is to Friends, a sitcom that started shortly after Frasier and lasted nearly as long. In Friends, all the emotional dynamics of the characters stuck in the situation are directed inwards; both conflict and romance emerge from within the group, creating a situation of increasingly anxious and incestuous tension. By the end of the show’s run, the characters of Friends are increasingly objectionable and two-dimensional, their neurotic characteristics having been refined from their lovable idiosyncrasies, and they’ve formed lasting relationships only within that logic of codependence. In Frasier, however, the situations are constantly derived from external situations, and their search for meaning and love outside of the family dynamic.

That constant influx of strangers into the show creates not the claustrophobia of Friends, but an openness, a constantly changing cast on whom to project the two main forms of the show — a comedy of manners, and a comedy of errors. It’s this mix of snobbery and farce, of excruciating vicarious embarrassment and physical humour, that underpins the show, and makes in a canvas for a discussion of class and meaning in ‘90s America. It’s what makes it, for me, a show worth returning to and examining, despite its manifest problems and contradictions.

Below I’ve cross-posted my essay on season 1, episode 8: ‘Beloved Infidel’. The episode explores some of the key themes of the early show, notably grief and betrayal, through a classic misunderstanding of the situation. If you’d like to follow along this writing project, please do subscribe for free at Tossed Salads and Scrambled Eggs. In the meantime, I’ll be back here at utopian drivel with fresh writing very soon.

Beloved Infidel

The discovery of a parent’s infidelity is somehow a triple threat to one’s psyche, as a child. It’s not just that a child is defensive over the other parent’s wellbeing, but they can also feel it as an attack on the family unit in general, an undermining of a collective happiness. As an adult, it’s much more complicated — whether it’s an ongoing affair or a past transgression. Was everything I thought as a child — the very model of a relationship — really a sham? Have I spent years admiring a man or woman not knowing they committed a transgression, my admiration itself a fraud? I thought one parent loved the other, and built a pure and perfect love between them, of which I, the child, am the sinless offshoot.

And yet, as an adult, shouldn’t you be more understanding, more aware of the imperfect nature of love? This is the question that strikes Frasier when, following a chance sighting of Martin comforting an old family friend at a restaurant, and with a little historical reconstruction through Niles’ diaries, they realise that their father had an affair with the woman some three decades earlier, coming to a head on a family holiday. How to come to terms with such a transgression when the victim of the infidelity, their mother, is long dead? Can they come to an understanding, or a bloody revenge? What since is a lie?

That, to me, is the disorienting aspect of parental adultery for the boys: to have to work back through happy memories and rework them with this new knowledge. We must have already realised by that age that our parents aren’t perfect, that love is more about habit than truth, and is complicated for that. In her brilliant dark satire on bourgeois marriage, A Severed Head, Iris Murdoch’s married couple Antonia and Martin are two people with differing views on marriage — Martin’s both weak and pragmatic, Antonia’s both sturdy and romantic. That’s not to suggest from Martin comes from a position of rationality or strength — he’s a weak and selfish man — but that Antonia, a motivated go-getter, believes it should just work, and if it doesn’t, it’s not for her. “Happiness is not the point,” she tells Martin, “We aren’t getting anywhere.” Martin replies that “One doesn’t have to get anywhere in a marriage. It’s not a public conveyance.”

Martin in Frasier is of a different view, knowing that relationships are hard, that people fuck up. But that’s not enough of an answer for the boys, whose mother and past has been desecrated. As discussed before, the absent mother is ripe for deification, but the marred past is harder to restore. In A Lover’s Discourse Roland Barthes remarks that a happy remembrance can be marked by the “intrusion” of the imperfect tense into a grammar of lovers — that is to say, memory of something happening implies, in the telling, its continuance, something that can only remind us of what we lost. The imperfect tense describes something that was happening, in the past story that is being recounted. It’s a fascinating, mysterious part of Barthes text that is compelling too. “The imperfect is the tense of fascination: it seems to be alive and yet it doesn’t move: imperfect presence, imperfect death; neither oblivion nor resurrection; simply the exhausting lure of memory. From the start, greedy to play a role, scenes take their position in memory: often I feel this, I foresee this, at the very moment when these scenes are forming.” Perhaps this lies at the root of the Crane boys anxiety around their father’s adulterous affair — it inserts itself into the smooth retelling of their happy childhood, and reopens it to the pain of doubt. Perhaps it’s not that “we had a wonderful summer by the lake,” but that “we were having a wonderful summer by the lake.” What continues in the new telling of things past in the imperfect tense?

It was worse than they expected — eventually the truth is revealed, and despite his earlier admission of guilt, it turns out it wasn’t their father who cheated, but their mother, the saint, Hester Crane. Martin lied precisely to keep Hester out of the imperfect tense. “I was just trying to protect her” he tells Frasier, “me you already had problems with.” With Hester dead, that past can’t be rewritten, and her truths remain locked in a tense that is final, closed. As Martin’s old friend, now also widowed, reassures him, “Frasier, your mother was a good person… they made a mistake.” That tone of finality makes it, as Barthes says, “an imperfect death”.

‘utopian drivel’ is a weekly essay series by Huw Lemmey. Please feel free to share and forward today’s newsletter with anyone who might be interested. For those just visiting, I send out a newsletter/podcast (about) once a week to paying subscribers — for less than $5 a month — and once a month for free subscribers. You can subscribe here, and, if you like it, please hit the like button. It helps other people find my newsletter.

Hey. Are you still writing these? Read the first fifteen and they are great. Keep going!