“Triggered?!?” has become a motto of the American Right online that seems to have gone endemic since the rise of the alt-right, a Pavlovian response to any sort of pushback or criticism. It’s typically American: unabashed and direct, claiming the person who objects to, for example, imprisoning children in concentration camps or gunning down preschoolers as a fundamental civil liberty, is suffering some sort of mental health episode, is precious to the point of breaking, or is hopelessly clueless about the tough realities of life. It’s such a ubiquitous catchphrase for this emotional steamroller of a worldview that it was even the title of the “book” of its most famous adherent, Donald Trump Jr. Don Jr is a man so coddled and preened by luxury that his face, his eyes resembling obsidian black marbles sliding towards his two cocaine holes and his injection-moulded teeth, could be used to illustrate a cautionary tale for Bolshevik children on the soul-wasting degradation of bourgeois life. Yet through the rhetorical power of this simple phrase he has managed to brand himself a hero marked by his rugged determination to triumph against a world that would deny him a voice. In its self-delusion, “triggered” is the latest chapter of the American Dream. Yet despite its success in the American marketplace of ideas, “triggered” never really took off in the UK except among the most yankophile of bullies. That’s not to say the sentiment doesn’t exist, but rather than this brash exclamation the British have resorted to a much more passive-aggressive, non-verbal equivalent, suitable to the local character: a Cry-Laugh Emoji Nation 😂😂😂.

What does the cry-laugh emoji symbolise? At its heart, it’s a symbol not of apathy, but of an active uncaring. On social media, it’s used to suggest that this thing that you are so exercised about is merely a source of humour for me. Often, it’s used in a reply when someone’s position is called up, when they’re proven incorrect, or (when accompanied by a fishing emoji), to suggest that this whole thing where I was shown up as wrong was actually an elaborate attempt to get a rise out of people (and it worked 😂🎣). As journalist Abi Wilkinson wrote in 2016, what’s most disturbing about the emoji isn’t the transparent thin-skinnedness dressed up as unbotheredness, but that often “the topic that appears to have amused them is the sort of thing you’d hope any empathetic, reasonable person would find unconscionably horrific.” I had long suspected that, as with “triggering the libs,” this was merely a result of social media’s tendency to wring out nuance and to privilege only the most antagonistic, nuance-free of political positions, combined with the degradation of news broadcasting into a form of algo-chasing team sport. Catch any Cry-Laugh people over a kitchen table then they, like me, will surely temper their slogans and admit a little humanity, no?

Now I’m not so sure. Wilkinson’s insightful analysis was five years ago. Has anything changed for the better in the half-decade since? In a fascinating article for local paper Kent Online this week, journalist Ed McConnell decided to track down some denizens of Cry-Laugh Nation. After 27 people drowned in the icy-cold English Channel last week trying to claim asylum in the UK, Kent Online posted coverage of the story on their Facebook page. McConnell decided to talk to some of the 96 people who responded to the tragedy with a ‘laugh’ response (Facebook’s own version of the Cry-Laugh emoji) and ask them ‘why?’. As I mentioned earlier, the “laughter” is a thin tissue that covers the real emotion: rage. “rapists murders (sic) nonces terrorists and they are robbing our country left right and centre cos they come from **** all and got no morals. Don’t like them never will there (sic) scum,” replied one, while many others responded, in words both long and short, by telling McConnell to fuck off. One could argue that being digitally doorstopped on Facebook Messenger would only entrench their positions, but I have to believe that, one-to-one, many of those questioned would maintain their contempt for human life. It is, of course, possible to argue for tighter immigration restrictions without such open contempt for migrants themselves (although I would also argue that dehumanisation and violence is an inherent part of the border regime, whether couched in polite language or not). But why, in Britain, is such cruelty delivered as a form of humour?

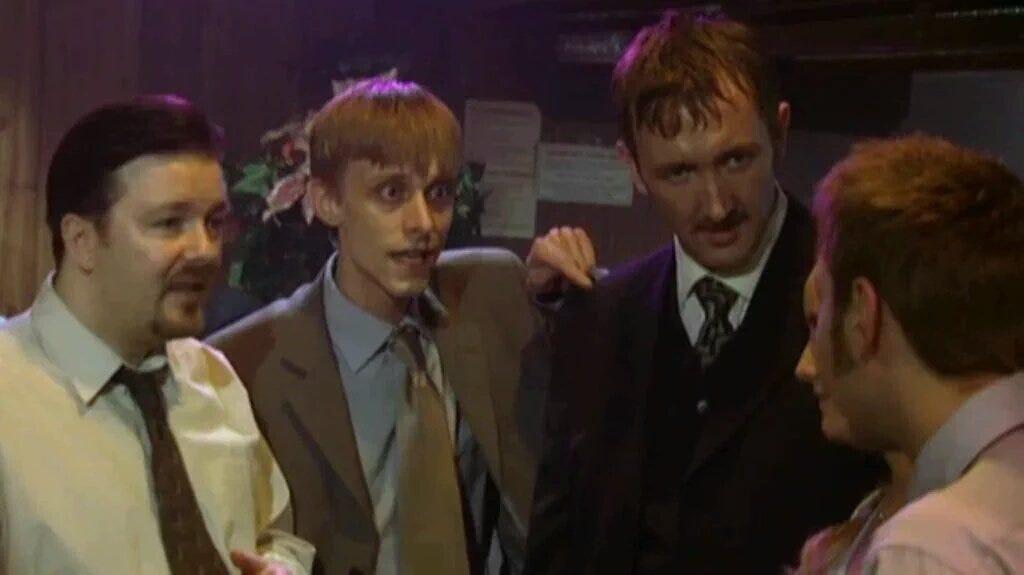

Mockery has always been at the heart of British humour. It’s the only nation where, when someone drops a plate in the school dining hall, or a pint glass at the bar, the smashing sound is immediately followed by a collective cheer at the misfortune of another, drawing attention to them right at the moment they’re at their most vulnerable. Mockery of one’s friends is an intimate bonding experience for the British, one which visitors and immigrants often struggle to understand as differing from hostility. And with good reason: the line between “banter” and hostility isn’t even a fine one, it’s an overlapping one. Friendship, often compulsory in work and school situations, is often laced with resentment, jealousy or distrust. Banter is a hostage’s language. Perhaps the best representation of Britain’s culture of banter is Chris “Finchy” Finch from the UK version of “The Office”. Finchy, a “bloody good rep”, is a bully. He bullies David Brent in order to assert his dominance, knowing full well that Brent can’t begin to defend himself because if he were to respond with anything other than good humour, he’d reveal himself to be incapable of “taking a joke”, the highest British virtue. Finch, like much of the show, is painful to watch, its depiction of British group dynamics so well observed. As the viewer, you’re on the opposite side of the table; you can see what fragile egos Finch, Brent and Territorial Army-obsessed Brent sidekick Gareth Keenan have, and how pitiful it is that the bully is regarded as the funny one.

Interestingly, the same dynamic doesn’t transfer to the US version of the show: Dwight Schrute might be many things, but insecure is not one of them, while Todd Packer, Finchy’s equivalent, is merely a crude boor, but lacks the ability to force others into complicity through fear of being seen as humourless. In America, sincerity is not a flaw but a virtue. In the UK, for all Tim Canterbury’s looks to camera and ironic remarks, he knows he can’t actually reply head on. Christopher Hitchens, remarking on poet Czesław Miłosz’s line that “irony is the glory of slaves”, hit the nail on the head: “the sharp aside and the witty nuance are the consolation of the losers and are the one thing that pomp and power can do nothing about.” Finch continues with this very British pomp and power, wielding his humour until Brent finally refuses the joke: surely one of the most satisfying moments in British comedy, and precisely because so many of us were raised hostages to “banter”.

Couching cruelty as humour and self-defence as weakness are two techniques that grease the wheels of British society. Cry-Laugh emoji serves both purposes, mocking others while, through it’s apparent lightness, being a defence against the dreaded British accusation of caring too much. For me, the purest cultural manifestation of the Cry-Laugh, the Cry-Laugh before the Cry-Laugh, was the BBC television show Top Gear. For 21 seasons Top Gear was one of the BBC’s flagship programmes, drawing in huge figures and presenter Jeremy Clarkson was its Chris Finch; the other presenters, Hammond and May, his banter hostages, their feeble comebacks only feeding his power, allowing him to demonstrate what a good sport he was. It was clear who was the dominant one, the group leader, the “Archbishop of Banterbury”. This model of English masculinity was not incidental to the show’s success: it was vital. It was the mocking banter that drew in legions of viewers who aspired to the same sort of cocksure blokeishness, an upper middle-class way of being with each other that was almost aspirational, alongside the sports cars, the beers, the jeans and sheux. Of course the show was offensive: not just the schoolyard homophobia and misogyny, but also explicit racist slurs, none of which were enough to get the show cancelled. But anyone complaining surely missed the point. The offensiveness wasn’t an unintended consequence of the jokes, it was the humour itself. It was Clarkson calling an Asian man a s****, or using the word n*****, and getting away with it, where the pleasure lay for the viewers, not because they were racist (although, by dint of accepting it, they were) but because it made them feel empowered by association. By laughing with Clarkson, you were on the side of the bully, you could still take a joke, you weren’t being bossed around by the humourless, the bumboys and feminists, the politically correct. The BBC and its producers knew as much; to rein in Clarkson would be to destroy the functioning of the show. I suspect the same dynamic lies behind the British Prime Minister’s refusal to wear a mask during a public health emergency, because it would make him look weak or, worse, woke; and a similar dynamic is behind the now-perennial argument about the BBC broadcasting the word “faggot” in Fairytale of New York; it’s not that anyone particularly wants to use the word faggot specifically, but rather the pleasure is in seeing it upset other people. Rather than releasing statements defending their decision not to censor such slurs, the BBC would be better off sending out an A4 page simply bearing one huge Cry-Laugh Emoji.

So where now for the Cry-Laugh Nation? It can only get worse before it gets better, if it ever does. Cry-Laugh Humanitarian Disasters will be joined by Cry-Laugh Human Rights abuses (after the recent jailing of nine climate activists, the Daily Star led with a group “hahaha” on its front page, surely missing a trick by not posting the Cry-Laugh Emoji instead). My prediction, as the rainy island gradually slips beneath the comforting waves of the North Atlantic, its food supply rotting in trucks at the Channel ports, the Royal Navy sinking the occasional French trawler every time the Tories flag in the polls, its hospital wards choking under disinvestment, is that the Cry-Laugh Emoji will solidify from instinct to politics. The Cry-Laugh Nation will discover a “if you don’t cry-laugh, you’ll cry” Blitz Spirit, where caring about a single other fucking person on earth will finally become totally taboo. Under a Union Jack superimposed with the yellow patriot’s hideous grimace, an entire movement will surely emerge offering, as fascist movements always do, a clear manifesto for banter-based action, a simple, blunt solution to the nation’s myriad problems: 😂 🇬🇧 😂 🇬🇧 😂 🇬🇧

Thank you again to all my subscribers. Please feel free to forward to anyone who might be interested.

For those just visiting, you can subscribe here, and, if you like it, please do share on social media etc. It helps other people find my newsletter.

Paid subscribers get access to the entire archive of 80+ essays, including posts such as this recent essay on Quentin Crisp, Larry Kramer and the 80s, this article about the British media’s obsession with Meghan Markle, this radio-visual essay on queer protest, and this short story about boys in Naples.