I love William Blake as much as the next man, but let’s be clear here, there is no such thing as ‘progressive patriotism’, and I lose respect for anyone whose mind, addled by sentiment or a desire for votes, starts to wander in that direction. I am proud to be an embodiment of those bogeymen figures of right-wing detachment, an ‘anywhere’ person. I love where I live, and wherever I have lived, I have always found things and people to love. And I loved my grandparents, obviously, and the smell of marmalade cooking in my grandfathers’ kitchen, or my grandmother taking me on a heritage steam railway, or whatever nostalgic things bring comfort and safety. But nice as those things are, that’s only because they’re my memories. It seems strange to me — actually, no, it pisses me off — to see those little memories or tastes tied to a much larger political entity, with the boundaries between personal sentimentality and political structure blurred, so my love of fish and chips, say — something I associate with my mum, and Morecambe prom, and a wet dog in the boot of the car — gets lumped in with a defence of the British Empire or the firebombing of Dresden. It seems a ludicrous proposition, but in reality, that’s what nationalism is, isn’t it? The smearing together of sentimentality and violence.

When you experience another nation’s patriotism, their fondness for their own sentimentalities, you experience something uncanny. You understand the frame, but the picture is all askew. I somehow understand what the Spanish are trying to do with the bold silhouette of a bull on hillsides, but it’s ludicrous, meaningless. Just an icon. No doubt, an English bulldog must induce the same baffled expression from others. And that’s where the real pantomime stupidity of patriotism comes in: everyone else’s national pride is both totally alien — foreign, let’s say — to everyone else, and yet so recognisable that the differences dissolve into meaninglessness. A whole earth of patriots, all of them totally blind to the fact their world of meaning is entirely relational. The patriots need each other to be each other’s foreigner. As those discreet English satirists Flanders and Swann concluded in their song on patriotic prejudice, “it’s not that they’re wicked, or naturally bad — it’s knowing they’re foreign that makes them so mad.”

Yet from a sleep of such sublime stupidity, monsters are dreamt. Somewhere in the nationalist imagination is the imperative to take specifics for the universal, and damn those who don’t feel the same. In post-war Germany, artists were hit with a crisis of representation following the collapse of a whole regime of national icons. Considering how images, icons, were used by the Nazis, how was it possible to start to represent real things without producing new icons, with all the potential for horror they might entail? The canvas represented a whole field on which meaning could be produced, but the painters who stood in front of them could only falter at the power they held as meaning-creators. They folded this political anxiety into a wider project. From the 19th century this clash between the field — the broad conceptual space that a canvas represented — and the form — the “thing” on which the artist focused, the thing being painted — had allowed for a productive tension. In The Dead Man by Manet, a toreador lies across the canvas; his body almost extends out into space, his feet pushing back the brown field on which he lies. His pink rag is like another canvas, and thick, wide brushstrokes create a drama within the paint.

Is the thing even interesting, or is the paint interesting? For a century this tension was exploited, pulled back and forth as artists and writers attempted to make sense of these ideas collapsing into each other. Was the field itself something sublime and holy? A deep plane of meaning? Or something revolutionary and communist, stripping away the kitsch pretensions of depicting mere ‘things’? Or — worse — a place for the dread unconscious to manifest its dark concerns?

In the immediate aftermath of the Second World War, these tensions were cultured to a head. In the United States, former leftists had theorised onto the field of the canvas a place of sublime high culture, the endpoint of what they saw as the modernist project against the kitsch. The history of art had rolled itself out and arrived here: “what was to go on the canvas was not a picture but an event," wrote critic Harold Rosenberg in 1952; “The big moment came when it was decided to paint…. Just TO PAINT. The gesture on the canvas was a gesture of liberation, from Value—political, aesthetic, moral.” They took all the aggressive meaning of the pre-war European expressionists but finished the job of modernism by abstracting it from mere things, and going deep into the field. These lads had every mark of genius; tortured and drunk, angry and full of intensity, the Abstract Expressionists splashed around their deep and brooding subconscious to an audience of New Yorkers desperate for art that meant something, and was big enough to furnish their apartments.

You can imagine the sort of shit that followed in their footsteps. New York had snatched Paris’ crown in the aftermath of occupation, and European artists made their own ham-fisted attempts to produce a Euro-version of this very American school. Art Informel and Tachisme looked to produce its own international style on the back of American abstract expressionism as a bulwark (funded by the CIA) against Communism. The Soviets, at first the pioneers of a genuinely bold and revolutionary modernist culture, had abandoned formal and abstract concerns under Stalin, adopting instead a party-led culture of socialist realism under Zhdanovshchina, returning to depictions of idealised Soviet citizens and workers. For a generation following the war, painters in Germany adopted this weak-sauce abstraction in an attempt to produce an art that evaded the representation of things, because, between the dogshit kitsch of Nazism and the state-mandated bodies of socialist realism, things felt too much like totalitarianism.

Such mediocre — maybe even traumatised — attempts to restart painting without representation must have had an effect on those who grew up on it. Georg Baselitz got a taste of the whole scene, having been raised in the GDR before being expelled from art school there for "sociopolitical immaturity". Bad painter! He crossed to West Berlin before the wall went up, and attended art school there, when Tachisme and Informel were at their height, but a young Baselitz, driven by his own intense desire to manifest the unconscious, wasn’t afraid of representing things. In his early twenties he pushed hard for the independence of the artist from furthering political ideologies. “The artist is not responsible to anyone,” he wrote. “His social role is asocial; his only responsibility consists of an attitude, an attitude to the work he does.” Such a view is deeply, big R, Romantic, tied in with a heroic view of the function of the artist. Other artists at the time, even when breaking from international abstraction and socialist realism, found different routes out of this dilemma, producing representations that addressed the challenge of photographic reproduction or the mass produced consumer image.

Not Baselitz; he returned to the representations of humans that preceded the fascist hiatus in the work of German expressionists. In the terrifying clatter of pre-Nazi Weimar Germany, these figures were represented as the fleshy human failpoints within a new industrialised economy; German artists reached “back” to supposedly “primitive” ways of representing people that they found in non-European, and particularly African, art. I needn’t reiterate how fucked up this is; anthropologists taking art from German colonies for display in Berlin museums were repurposed as representations of the catastrophes of alienation. Ironically, in the post-war period this form of expressionism was seen as somehow very German.

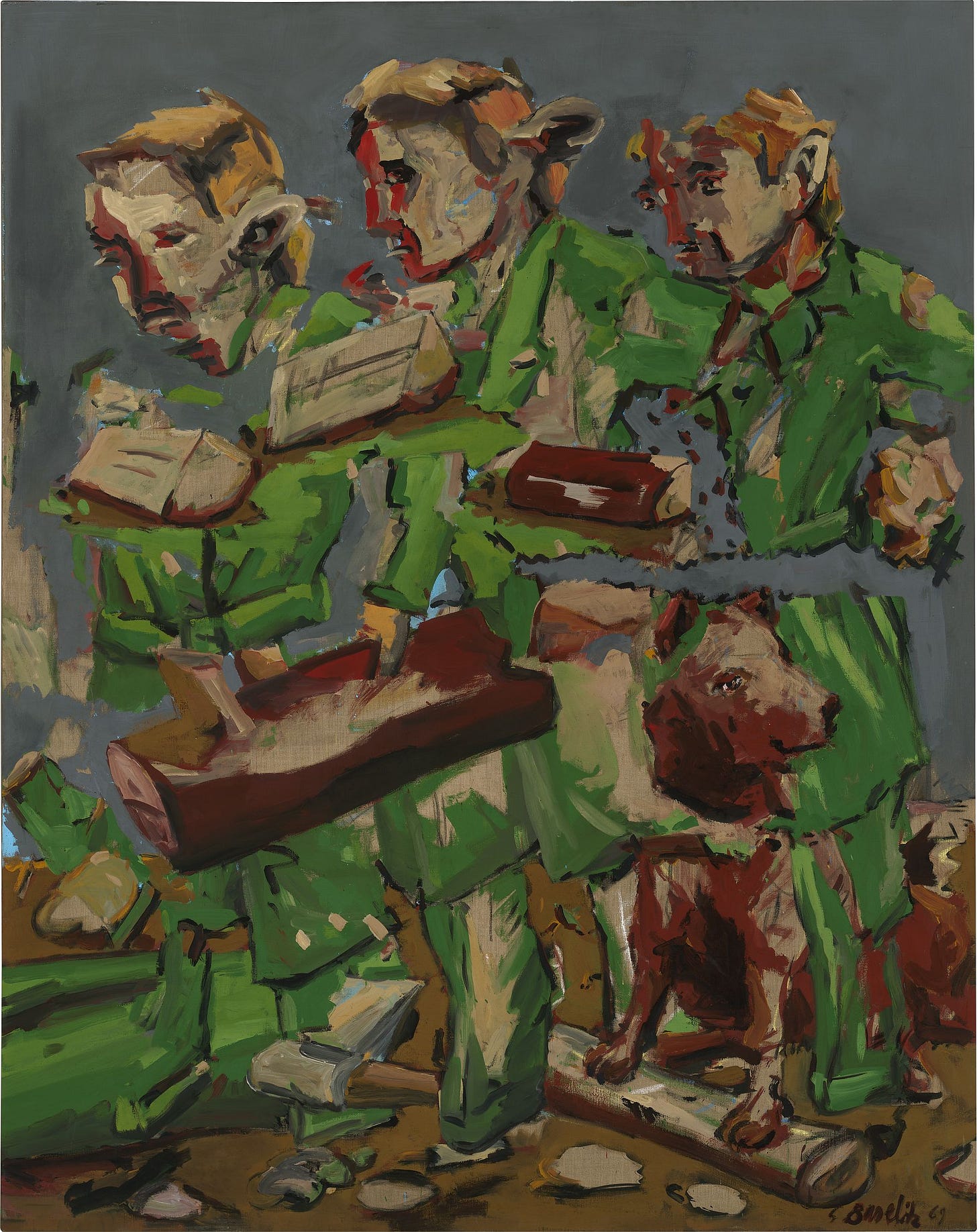

Painting in this visual language, Baselitz’s first works looked at these figures, stood out against a dark ground, as an attempt to revisual the human in the wake of the Holocaust. They are barely feasible as human figures, smeared and unstable, and deeply abject. In works like Die große Nacht im Eimer and Der nackte Mann boys or young men grab their engorged, outsized penises, their faces distorted beyond recognition as humans. But soon Baselitz’s representation of the figure was moving on to a new type, combining with his expressionist form a set of motifs that date back to the late Romanticism of the end of the 19th Century. These were the figures and motifs that were self-consciously depicted in order to produce a German national identity in the early years of German nationhood. They are, in a manner of speaking, the bull and bulldog of Germany, wrestled from the dark national imagination of the forest and mountain, a Germany tied to the land and unencumbered by the city and its degrading electric light. A series of German archetypes seem to literally reappear through the rubble of war; the Shepherd, the Eagle, the Woodcutter, the Hound and the Hare. Baselitz called them the Neue Typ, although they look just like the old one. Sure, they are fractured, their clothes tattered, but they are curiously solid. Something of the new type of German has emerged undestroyed. Despite a lifetime forcefully claiming that, as an artist, he is outside the constraints of the political, Baselitz told curator Norman Rosenthal “...what I could never escape, was Germany, and being German… [I] completely threw myself into this business of being German.”

Within both his claim to be autonomous, and his return to the type, the icon, of the German character, shit-stained and muddy, we see something of this attempt to reanimate sentiment as heroics. There is something of value in being German, they seem to say, something only Germans know. Nationalism relies upon its adoption as common sense, as something natural, and, like a good hunter, it covers its tracks as it goes, showing any sign that all these types are produced. It relies upon familiarity and novelty, the same shit repackaged.

The God of Nations needs to be not only fed frequently with fresh blood, but honoured with new idols.

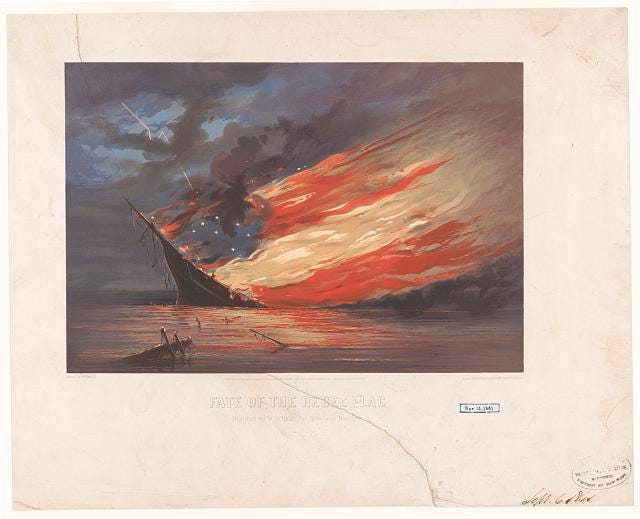

I thought of Baselitz’s ‘new types’ when I watched crowds pull down the Confederate monuments in the American South this spring. In fact, they’re not Confederate monuments at all; they are Jim Crow monuments, active attempts to reassert a social and economic dominance that Reconstruction had barely chipped away at. They went up years after the civil war, a concerted attempt by white supremacists to manufacture heroes they felt their ideas deserved. Like in Germany, the catastrophe of war had destroyed a myth of supremacy, but they felt themselves wronged, and wanted to restore some national archetypes they felt gave them dignity.

When I see people, racist people, claim that those who dismantle statues of slave traders and Confederate soldiers are akin to the Taliban, desecrating idols, I want to ask them — do you regard these brass and tin Confederates as your Gods? I can’t help but think they do. The brutality of white people has always required divine sanction, and American whiteness practices its own form of ancestor worship, one that masquerades as heritage.

But when they say “we learn from these statues”, well there, I can’t help but agree. The icons — in this case, of those who betrayed their country for their race, an action that still heralds them as heroes and patriots, even within the country they betrayed — are things that linger past the destruction of the cause, that carry its message on to future generations. White Americans do learn from the statues — they learn that the sacrifice needed to maintain white supremacy is a higher calling than mere patriotism. Black Americans do learn from statues — they learn that even their most heroic deeds will never be as important to America as their most abject persecutions.

The statues are as much about an insecure people — a population of losers — reaffirming to themselves a belief of which they can never be certain. James Baldwin, one of America’s greatest moralists (in the best sense of the word) referred to this insecurity, formed from the sexual violence that was habitually used against enslaved women, as being the fact “that no white American is sure he is white”. Having built a system of racial supremacy, white men and women are haunted by themselves, and pour ever more physical, mental, and cultural resources into defending it. This is not to simplify the situation, to say that the cause of white supremacy is insecurity; behind white supremacy is a web of complex factors, the most notable of all being financial greed. But rather, it is to say that the beliefs that justify racism (and most forms of chauvinism) are made of cardboard, and must constantly be reinforced. As Baldwin noted of white people’s fear of black people, “they have always known that you were not a mule. They have always known that no-one wishes to be a slave. They have always known that the bales of cotton and the textiles mills and entire metropolises built on black labour, that the black was not doing it out of love. He was doing it under the whip.” It is the weakness of the beliefs that make them so insidious, so much in need of constant reiteration.

New idols and types, new heroes, must be constantly manufactured for the nation, for nationalism is an ideology of ever diminishing returns, and has nothing to offer the human mind or soul. Nobody becomes more thoughtful, funnier, kinder or more interesting as they become more filled with patriotic fervour. Love of nation is predicated on a malignant fear of the different, and so the profitable process of building national myth and pride continues until it unleashes itself in racist violence. Even when it seems to be destroyed, it lingers and feeds on insecurity until, in a fit of sentimentality, it starts the whole process again. There’s nothing good in a love of country that isn’t, in fact, the love of something else, something far more human — of a scent in the air, or a half-remembered song — that has been exploited, and rendered as the product of the nation. We must distrust anyone who claims it as any good at all.

‘utopian drivel’ is a weekly essay series by Huw Lemmey. Please feel free to share and forward today’s newsletter with anyone who might be interested. For those just visiting, I send out a newsletter/podcast (about) once a week to paying subscribers — for less than $5 a month — and once a month for free subscribers. You can subscribe here, and, if you like it, please hit the like button. It helps other people find my newsletter.

Really loved this essay. Have sent to a few people this week, and made it the second link in my weekly newsletter today: https://carrozo.substack.com/p/half-a-loaf